Abstract

Hypertrophic cranial pachymeningitis (HCP) is an uncommon disorder that causes a localized or diffuse thickening of the dura mater and has been reported to be infrequently associated with systemic autoimmune disorders such as Wegener's granulomatosis, rheumatoid arthritis, sarcoidosis, Behçet's disease, Sjögren syndrome, and temporal arteritis. Here, we report a case of HCP initially presented with scleritis and headache in a patient with undifferenciated connective tissue disease (UCTD). HCP was initially suspected on brain magnetic resonance imaging and defined pathologically on meningial biopsy. Immunologic studies showed the presence of anti-RNP antibody. After high dose corticosteroid therapy, the patient's symptoms and radiologic abnormalities of brain were improved. Our case suggested that HCP should be considered in the differential diagnosis of headache in a patient with UCTD presenting with scleritis.

Hypertrophic cranial pachymeningitis (HCP) is a rare disease characterized by localized or diffuse thickening of the dura mater of brain. A variety of conditions including intracranial hypotension, infections, systemic autoimmune/vasculitic disorders, malignancy, and meningioma can result in thickened abnormally enhancing dura mater on gadolinium-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (1). Compression of anatomic structures by thickened cranial dura mater may cause clinical symptoms. Headache, cranial nerve palsies, and ataxia are the most common clinical manifestations. HCP may be infrequently associated with other fibrosclerotic diseases including sclerosing cholangitis, Riedel thyroiditis episcleritis, mediastinal fibrosis, and inflammatroy pseudotumor (1). The diagnosis of undifferentiated connective tissue disease (UCTD) can be made in patients with clinical symptoms and serological abnormalities suggestive of an autoimmune disease, but not sufficient to fulfill the diagnostic criteria for a defined CTD. Arthralgias, arthritis, Raynaud's phenomenon, mucocutaneus manifestations, sicca symptoms, and leucopenia are the most frequent manifestations of UCTD (2).

Scleritis is characterized by a chronic inflammation that involves the outermost coat and skeleton of the eye. Many patients with scleritis have systemic immune-mediated disease such as rheumatoid arthritis, Wegener's granulomatosis, relapsing polychondritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, inflammatory bowel disease, spondyloarthropathies, and polyarteritis nodosa (3). We have found only one case report of pachymeningitis in a patient with UCTD (4). There has been only a few case report of pachymeningitis with scleritis (5, 6).

To our knowledge, there is no previous report of pachymeningitis in a patient with UCTD presenting with scleritis. Here, we describe a 37-yr-old male patient with UCTD who suffered from scleritis and intracranial symptoms caused by pachymeningitis.

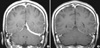

A 37-yr-old man was referred to our emergency room with a provisional diagnosis of a subdural hemorrhage in April 18, 2009. He has complained of history of headache with intermittent nausea and vomiting for two weeks. Brain computed tomography (CT) was done at local clinic to evaluate these symptoms and unenhanced CT scans showed high-density areas along the left tentorium cerebelli. He had been managed with prednisolone (5-30 mg/day) by ophthalmologist in our hospital under the diagnosis of scleritis since January 2008. Thirty milligrams of prednisone was administrated for 7 days initially and then tapered. At the time of symptom developing, the patient was being treated with prednisone 10 mg. The patient has complained of intermittent hand joint pain, swelling, and Raynaud's phenomenon for 3 yr. He had neither other past history nor familial history. He denied a history of head trauma. The initial vital signs were stable. On physical examination, both eyes appeared red. No arthritic pain was observed. The rest of the clinical examination was normal including neurological examination. Complete blood cell counts were within normal limits. Blood analysis showed an erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 48 mm/hr and C-reactive protein of 44.49 mg/L (normal <3.0 mg/L). The values for blood glucose, liver function, renal function, electrolytes, C3, and C4 were their normal ranges. In the tests for autoantibody, the titer of antinuclear antibody was 1:1,600 and anti-ribonucleoprotein (RNP) antibody 63.42 EU. But, antibodies to double stranded DNA, Sm, Ro, La, Scl-7, Jo-1, centromere, nucleosomes, and histone were negative. Rheumatoid factor, anti-CCP antibody, and ANCA were also negative. Tests for syphilis, hepatitis B surface antigen, anti-HBs antibody, anti-HCV antibody, anti-HTLV-1 antibody, and anti-HIV were negative. The level of serum angiotensin-converting enzyme was normal. The urinalysis was normal. CSF examination showed increased opening pressure (250 mmH2O), proteins (99 mg/dL), and cells (28/µL, lymphocyte 98%). CSF cultures and staining for acid-fast bacilli, bacteria and fungi were negative. The patient complained of diplopia on the 2nd hospital day and peripheral type facial palsy on the 10th hospital day. A chest radiography showed calcified nodules in the right upper lobe. Chest CT showed 3.3×1.6 cm sized irregular soft tissue density in the left upper anterior pericardial region (Fig. 1A). Brain MRI showed a left tentorium cerebelli lesion that was iso-intensity on T1 weighted MRI and hypointensity on T2-weighted imaging with marked enhancement after gadolinium (Fig. 2A). On the 19th hospital day, the patient underwent biopsy of left tentorium cerebella. Meningeal biopsy showed fibrosis accompanied by the infiltration of chronic inflammatory cells without evidence of vasculitis or granuloma (Fig. 3). From the 3rd hospital day after meningeal biopsy, 20 mg of intravenous dexamethasone was administered for 6 days, then changed to oral prednisolone (1 mg/kg) with gradual tapering. Follow-up MRI, performed at 4 weeks after the initial glucocorticoid therapy, showed much regression of dural enhancement (Fig. 2B). A follow-up chest CT scan 5 months after the initial glucocorticoid therapy demonstrated a marked decrease of the size of the pericardial mass (Fig. 1B). He recovered from diplopia and facial nerve palsy with glucocorticoid therapy. Currently, after 10 months of follow-up after introduction of glucocorticoid, the patient is doing well with low doses of glucocorticoid.

Hypertrophic pachymeningitis is defined as localized or diffuse thickening of the dura mater. Radiculopathy, myelopathy or a combination of the two has also been observed in patients with hypertrophic spinal pachymeningitis (7). Chief symptoms of hypertrophic cranial pachymeningitis are headache with or without intracranial neurologic manifestations such as cranial neuropathy and cerebellar dysfunction (8). As in this case, a patient with cranial pachymenigitis presenting with headache may be initially misdiagnosed as acute subdural hemorrhage (9, 10). Fibrous encasement and ischemic damage to cranial nerves may lead to cranial nerve palsies (11). Two patterns of cranial nerve involvement have been described, based on the site of dural inflammation, cavernous sinus to superior orbital fissure involvement (anterior involvement) and falcotentorial to posterior fossa dural involvement (posterior involvement). In the case of posterior involvement, cranial nerves 5 to 12 may be involved, with involvements of the 8th nerve being the most common (8). In our case, the patient suffered from facial nerve palsy.

MRI is very useful to evaluate dura mater disease. In case of pachymeningitis, MRI showed characteristic findings such as hypo-isodense dura on T1 and T2WI and marked enhancement after contrast administration, but these findings are not pathognomonic of cranial pachymeningitis. Many conditions including intracranial hypotension, infections, metastatic or infiltrative malignancy, sarcoidosis, vasculitis, and connective tissue diseases can cause thickening of the dura mater. In our case, we could exclude the possibility of intracranial hypotension, infections and malignant tumors as cause of dural thickening on the base of the results of CSF study and histopathologic examination. Connective tissue diseases such as Wegener's granulomatosis, rheumatoid arthritis, sarcoidosis, Behçet's disease, and Sjögren syndrome have been reported to be associated with hypertrophic cranial pachymeningitis (1). In this case, arthritis and Raynaud's phenomenon for more than three years and the presence of with scleritis (3). There has been only a few case report of HCP with scleritis. S anti-nuclear antibody and anti-RNP antibodies suggested a systemic autoimmune disease, but the patient did not meet the existing classification criteria for a connective tissue disease. Therefore, the patient was diagnosed as having undifferentiated connective tissue. There has been one case report of hypertrophic cranial pachymeningitis in a patient with UCTD (1).

Scleritis which is characterized by a chronic inflammation that involves the outermost coat and skeleton of the eye is often associated with immune-mediated systemic inflammatory condition (3). Rheumatoid arthritis and Wegener's granulomatosis are known to be the most common systemic immune mediated diseases associated with scleritis (3). UCTD is reported to be rarely associated with scleritis (3). Ueda et al. (5) reported a case of scleritis with pachymeningitis which was diagnosed on the basis of brain MRI findings. Starosta et al. (6) reported a case of pachymenigitis with scleritis in a patient with RA. As far as we know, this is the first report of HCP in a patient with UCTD presenting with scleritis.

HCP may be infrequently associated with other fibrosclerotic diseases such as sclerosing cholangitis, episcleritis, Riedel thyroiditis, testicular fibrosis, mediastinal fibrosis, and inflammatoy pseudotumor (1). Inflammatory pseudotumor is a quasineoplastic lesion consisting of inflammatory cells and myofibroblastic spindle cells. Inflammatory pseudotumor is thought to be associated with either infection or autoimmune mechanism (12).

The differential diagnosis of pericardial masses includes pericardial cyst, hematoma, metastatic neoplasm, and primary neoplasm (13). Metastatic neoplasm such as mesothelioma, lymphoma, sarcoma, liposarcoma may be suggested by CT findings of effusion and irregularly thickened pericardium or pericardial mass. Primary benign pericardial tumors include hemangioma, lipoma, teratoma, and fibroma. Low attenuation and depiction of calcium or fat in a pericardial mass on CT images suggest lipoma and teratoma, respectively. Malignant primary tumors include lymphoma, mesothelioma, sarcoma, and liposarcoma and pericardial effusion are frequently associated. Biopsy was not done because there was a high operative risk and was not pericardial effusion which was usually accompanied with a lymphoma. Although MRI and biopsy were not performed for pericardial mass, the remarkable corticosteroid response, physiologic amount of pericardial effusion, and CT findings favor a diagnosis of inflammatory pseudotumor in our case.

There is no consensus on the adequate therapeutic management of HCP. Although spontaneous resolution has been reported (14), glucocorticoid therapy has been considered as the mainstay of treatment in patients with HCP. If clinical manifestations are resistant or dependent to glucocorticoid therapy, additional methotrexate or azathioprine may be helpful (15, 16).

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 1Enhanced computed tomography of the chest. (A) In April 2008, irregular soft tissue density measuring about 3.3×1.6 cm was seen in the left upper anterior pericardial region (arrow). (B) In October 2008, 5 months after the initial glucocorticoid therapy, follow up image demonstrated more regression state of the left upper anterior soft tissue density, measuring about 1.7×0.7 cm (arrow). |

| Fig. 2Magnetic resonance image of the brain. (A) On the 3rd hospital day, axial T1-weighted contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance image shows diffuse thick dural enhancement along the left tentorium and left cerebellar surface. (B). In 4 weeks after the initial glucocorticoid treatment, follow-up magnetic resonance image demonstrated nearly complete regression of dural enhancement. Only very thin dural enhancement remained. |

References

1. Kupersmith MJ, Martin V, Heller G, Shah A, Mitnick HJ. Idiopathic hypertrophic pachymeningitis. Neurology. 2004. 62:686–694.

2. Mosca M, Tani C, Bombardieri S. A case of undifferentiated connective tissue disease: is it a distinct clinical entity? Nat Clin Pract Rheumatol. 2008. 4:328–332.

3. Smith JR, Mackensen F, Rosenbaum JT. Therapy insight: scleritis and its relationship to systemic autoimmune disease. Nat Clin Pract Rheumatol. 2007. 3:219–226.

4. Lampropoulos CE, Zain M, Jan W, Nader-Sepahi A, Sabin IH, D'Cruz DP. Hypertrophic pachymeningitis and undifferentiated connective tissue disease: a case report and review of the literature. Clin Rheumatol. 2006. 25:399–401.

5. Ueda S, Hayashi Y, Kono T, Norito M, Hishida E, Shraki K. A case of pachymeningitis with impaired ocular motility. Rinsho Ganka. 2006. 60:553–557.

6. Starosta MA, Brandwein SR. Clinical manifestations and treatment of rheumatoid pachymeningitis. Neurology. 2007. 68:1079–1080.

7. Pai S, Welsh CT, Patel S, Rumboldt Z. Idiopathic hypertrophic spinal pachymeningitis: report of two cases with typical MR imaging findings. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2007. 28:590–592.

8. Mamelak AN, Kelly WM, Davis RL, Rosenblum ML. Idiopathic hypertrophic cranial pachymeningitis. Report of three cases. J Neurosurg. 1993. 79:270–276.

9. Im SH, Cho KT, Seo HS, Choi JS. Idiopathic hypertrophic cranial pachymeningitis presenting with headache. Headache. 2008. 48:1232–1235.

10. Song JS, Lim MK, Park BH, Park W. Acute pachymeningitis mimicking subdural hematoma in a patient with polyarteritis nodosa. Rheumatol Int. 2005. 25:637–640.

11. Hatano N, Behari S, Nagatani T, Kimura M, Ooka K, Saito K, Yoshida J. Idiopathic hypertrophic cranial pachymeningitis: clinicoradiological spectrum and therapeutic options. Neurosurgery. 1999. 45:1336–1344.

12. Narla LD, Newman B, Spottswood SS, Narla S, Kolli R. Inflammatory pseudotumor. Radiographics. 2003. 23:719–729.

13. Wang ZJ, Reddy GP, Gotway MB, Yeh BM, Hetts SW, Higgins CB. CT and MR imaging of pericardial disease. Radiographics. 2003. 23:S167–S180.

14. Nishio S, Morioka T, Togawa A, Yanase T, Nawata H, Fukui M, Hasuo K. Spontaneous resolution of hypertrophic cranial pachymeningitis. Neurosurg Rev. 1995. 18:201–204.

15. Choi IS, Park SC, Jung YK, Lee SS. Combined therapy of corticosteroid and azathioprine in hypertrophic cranial pachymeningitis. Eur Neurol. 2000. 44:193–198.

16. Bosman T, Simonin C, Launay D, Caron S, Destee A, Defebvre L. Idiopathic hypertrophic cranial pachymeningitis treated by oral methotrexate: a case report and review of literature. Rheumatol Int. 2008. 28:713–718.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download