Abstract

We report a case of primary fibroepithelial polyps (FEPs) in the middle of both ureters in a patient with advanced gastric cancer and acute renal failure. Ureteral FEPs are rare benign lesions, and multiple, bilateral lesions are extremely rare. To our knowledge, this report is the seventh case of bilateral FEPs in the literature. Our case has clinical implications because FEPs should be considered as a cause of ureteral obstruction inducing acute renal failure in advanced gastric cancer.

Advanced cancer of the abdomen and pelvic organs often causes urinary obstruction by direct extension or compression. Urologists commonly consider an indwelling ureteral stent or percutaneous nephrostomy to treat obstructive uropathy in advanced cancer.

Primary ureter tumors can be epithelial or nonepithelial in origin. Fibroepithelial polyps (FEPs) are the most common nonepithelial tumor and originate from mesodermal elements (1, 2). They have a fibrous core covered by normal urothelium and are smooth-margined, and cylindrical, sessile, or even frond-like (3). Ureteral FEPs are usually located in the proximal third of the ureter, and are predominately on the left side, where about 70% of such lesions occur (3, 4). They are usually solitary, and reports of multiple, bilateral polyps are extremely rare (2). We report the seventh case of bilateral FEPs, which was diagnosed by ureteroscopy and proven by biopsy. All the polyps could not be removed since there were more than 20 small separate lesions in each ureter. The patient showed a clinical picture of complete uretral obstruction and acute renal failure that was not due to malignant ureteral obstruction, but to FEPs in both ureters.

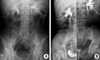

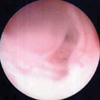

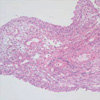

A 67-yr-old man presented to the hospital, complaining of dark-colored urine intermittently for approximately 4 yr. He had also experienced intermittent bilateral flank pain over the previous 2 months. His medical history included a total gastrectomy for advanced gastric cancer 2 yr earlier and chemotherapy with paclitaxel and cisplatin. There was no evidence of a radiologic abnormality in the urinary tract at that time or on the most recently obtained follow-up abdominal computed tomography (CT) image. The physical examination of the patient was unremarkable. On laboratory examination, there was microscopic hematuria. The blood chemistry included serum creatinine of 10.7 mg/dL and serum potassium of 5.1 mM/L. Renal ultrasound (US) showed moderate hydronephrosis in both kidneys and dilatation of both upper ureters. It was thought that the bilateral obstructive uropathy was due to direct extension or external compression of both ureters by advanced gastric cancer metastases. Therefore, percutaneous nephrostomy catheters were placed bilaterally on an emergency basis and antegrade pyleograms were obtained. The third day after the urinary diversion, the serum creatinine had decreased to 1.3 mg/dL. The antegrade pyleograms revealed moderate dilatation in both renal pelvises and upper ureters, and the mid to lower ureter could not be visualized, even after 1 hr, implying complete ureter obstruction (Fig. 1A). Bilateral retrograde ureterograms (RU) were attempted after a normal cystoscopic examination, which revealed a narrowed ureter caliber bilaterally, suggesting long segmental strictures from the upper to middle ureter bilaterally (Fig. 1B). Since the percutaneous nephrostomy tubes would reduce the patient's quality of life and cause a number of problems, such as discomfort and tube displacement, we inserted double-J ureteral stents in both ureters and then we clamped both nephrostomy catheters to ensure proper urine drainage through the ureteral stent. Unfortunately, the patient developed anuria immediately after removing both percutaneous nephrostomy tubes, and this progressed to hydronephrosis and flank pain. Urine cytology from the nephrostomy catheters and both ureteral catheters was negative for malignancy. We could not find any ureteral or peri-ureteral lesion on either side, except for moderate hydronephrosis and dilatation of the ureter on abdominal CT. Surprisingly, ureteroscopic evaluation showed over 20 small, separate FEPs from the middle to upper ureters bilaterally (Fig. 2). Furthermore, on cystoscopy, the lumens of the double-J stents were filled with small polyps without urine passage. We could not remove all of the lesions because the polyps were located diffusely over the entire ureter wall and we could not find any normal ureter mucosa. Furthermore, the ureter lumens were so narrow that we could not resect the polypoid lesions while avoiding ureter injury. We were concerned about whether the remaining ureters would function normally without a long segmental ureteral stricture after the polyps were removed, even if it proved possible to remove all of the lesions. That is why we decided to maintain the percutaneous nephrostomy catheters. Histological examination of the resected specimen showed FEPs consisting of a core of fibrovascular tissue covered by a normal layer of transitional epithelium. Mild chronic inflammatory cell infiltration was seen in the stroma (Fig. 3).

Fibroepithelial polyps are mesodermal tumors that consist of a fibrous core covered by normal urothelium (3). They often have smooth surfaces and are cylindrical, sessile, or even frond-like. FEPs can occur in newborns and adults older than 70 yr, but occur most commonly between the second and fourth decades (5). The male to female ratio is 3 to 2 and the left ureter is involved more commonly than the right, with about 70% of lesions occurring in the left ureter (3, 4). In adults, approximately 62% of these tumors occur at the ureteropelvic junction or in the upper ureter (3, 4). They can be smaller than 50 mm, ranging in size from 1 to 50 mm, with the largest reported polyp measuring 14 cm (6).

Macroscopically, FEPs can be divided into two categories: long slender cylindrical masses that have a thin stalk connected to the ureteral wall, or shorter, wider masses with multiple finger-like projections attached to a single base mass (7). The etiology of these tumors is not clear. Chronic irritation, infection, hormonal imbalance, allergic factors, and developmental defects have all been suggested (8).

Gross or microscopic hematuria is the most common presenting clinical finding in adults (1, 9). The patients may be either completely asymptomatic or have unrelated symptoms. Consequently, many patients are diagnosed late or incidentally for their persisting symptoms despite seeking medical care earlier in the course of the disease (1, 10).

It is not always easy to document radiological findings that would lead to a diagnosis of FEP on either intravenous urography (IVU) or RU, as in our case. On IVU, hydronephrosis is detected in 59% of cases. Ureteral filling defects are detected in 26% and 48% of cases using IVU and RU, respectively (1). Our patient had an intermittent 4-yr history of dark-colored urine, which was probably hematuria. The renal US and abdominal CT findings from 4 yr ago to the most recent follow-up imaging study, obtained 6 months earlier, showed no specific abnormalities in the kidneys or ureters. These findings suggest that the slow-growing FEPs, which were probably congenital in origin, could not be detected with ordinary radiological studies. This also warns us to evaluate patients with hematuria thoroughly, including endoscopy in selected patients.

Multiple, bilateral FEPs are extremely rare. No previous studies have specifically reported bilateral, multiple FEPs located in mid-ureter. Our case has many other unusual features: the location in mid-ureter bilaterally; the clinical appearance with normal radiologic findings 6 months before the diagnosis was made and the delayed diagnosis on ureteroscopy; and the inability to remove the masses completely due to their small size and number. This report calls attention to a rare manifestation of ureteral FEPs, which should be included in the differential diagnosis of long-lasting, undiagnosed microscopic or gross hematuria with normal initial radiologic findings. In this situation, ureteroscopy could also be attempted to obtain a diagnosis and devise the proper management. Moreover, bilateral FEPs should be included in the differential diagnosis of obstructive uropathy in advanced abdominal cancer patients.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Radiologic images. (A) Antegrade pyelography through the nephrostomy catheter. The antegrade pyleograms revealed moderate dilatation in both renal pelvises and upper ureters, and the mid to lower ureter could not be visualized, even after 1 hr, implying complete ureter obstruction. (B) Retrograde ureterogram showing a long segmental filling defect in the upper to middle ureter corresponding to the fibroepithelial polyps.

References

1. Franco I, Choudhury M, Eshghi M, Bhalodi A, Addonizio JC. Fibroepithelial polyp associated with congenital ureteral diverticulum: report of 2 cases. J Urol. 1988. 140:598–600.

2. Kiel H, Ullrich T, Roessler W, Wieland WF, Knuechel-Clarke R. Benign ureteral tumors. Four case reports and a review of the literature. Urol Int. 1999. 63:201–205.

3. Mariscal A, Mate JL, Guasch I, Casas D. Cystic transformation of a fibroepithelial polyp of the renal pelvis: radiologic and pathologic findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1995. 164:1445–1446.

4. Liddell RM, Weinberger E, Schofield DE, Pelman RS. Fibroepithelial polyp of the ureter in a child. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1991. 157:1273–1274.

5. Van Poppel H, Nuttin B, Oyen R, Stessens R, Van Damme B, Verduyn H. Fibroepithelial polyps of the ureter. Eur Urol. 1986. 12:174–179.

6. Lavelle JP, Knisely AS, Bellinger MF. Benign fibroepithelial polyps causing symptomatic bilateral intermittent hydroureteronephrosis. J Urol. 1997. 158:569.

7. Psihramis KE, Hartwick W. Ureteral fibroepithelial polyp with positive urinary cytology. Urology. 1993. 41:387–391.

8. Cassar Delia E, Joseph VT, Sherwood W. Fibroepithelial polyps causing ureteropelvic junction obstruction in children-a case report and review article. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2007. 17:142–146.

9. Bartone FF, Johansson SL, Markin RJ, Imray TJ. Bilateral fibroepithelial polyps of ureter in a child. Urology. 1990. 35:519–522.

10. Bolton D, Stoller ML, Irby P 3rd. Fibroepithelial ureteral polyps and urolithiasis. Urology. 1994. 44:582–587.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download