Abstract

Cystinuria is an inherited renal and intestinal disease characterized by defective amino acids reabsorption and cystine urolithiasis. It is unusually associated with neurologic symptoms. Mutations in two genes, SLC3A1 and SLC7A9, have been identified in cystinuric patients. This report presents a 13-yr-old boy with cystinuria who manifested difficulty in walking, ataxia, and mental retardation. Somatosensory evoked potential of posterior tibial nerve stimulation showed the central conduction dysfunction through the posterior column of spinal cord. He was diagnosed non-type I cystinuria by urinary amino acid analysis and oral cystine loading test. We screened him and his family for gene mutation by direct sequencing of SLC3A1 and SLC7A9 genes. In this patient, we identified new missence mutation G173R in SLC7A9 gene.

Cystinuria is an autosomal recessive disorder of amino acids transport affecting the epithelial cells of the renal tubules and gastrointestinal tract. It is characterized by increased urinary excretion of cystine and the dibasic amino acids (ornithine, lysine and arginine), and manifested by recurrent renal stones due to the poor solubility of cystine in the urine. There are three different types of cystinuria according to the urine phenotype in heterozygotes: type I (MIM220100), non-type I (MIM600918), and mixed. In type I cystinuria, heterozygotes have a normal pattern of amino acid excretion in the urine (1). In non-type I cystinuria, heterozygotes have a variable degree of hyperexcretion of cystine and diabasic amino acids. Patients with mixed type cystinuria inherit type I and non-type I alleles from either parent.

Two genes responsible for cystinuria have been identified. The first locus gene, SLC3A1, located on chromosome 2p-16.3-21 encoding rBAT (related to b0,+ amino acid transporter), was identified to be the cause of type I cystinuria in 1994 (2). A second locus gene that is responsible for non-type I cystinuria was mapped on chromosome 19q12-13.1. encoding for b0,+ AT (b0,+ amino acid transporter) by linkage analysis and later identified as SLC7A9 by International Cystinuria Consortium (3). At present, 79 mutations in SLC3A1 were reported and over 50 mutations in SLC7A9 have been described so far (1).

There have been several reports of cystinuria associated with neurological manifestations; mental retardation, muscular dystrophy, hypotonia and dwarfism, paroxysmal dyskinesia, migraine, subacute combined degeneration of the spinal cord, and cerebellar atrophy (4-6). In terms of pathogenetic correlation between cystinuria and various neurological conditions, it is still undetermined whether these two conditions share a common pathogenesis or are coincidental. Genotypic evaluation of cystinuria associated with neurological manifestations has not been reported before.

We report a case of non-type I cystinuria associated with neurologic symptoms and identified new missence mutation G173R in SLC7A9 gene.

A 13-yr-old boy was admitted due to increasing difficulty in walking and clumsiness of the movement, noticed at about 5 yr of age by his mother. Birth history and early neurodevelopment until the age of 1 yr were unremarkable. He held his head at 3 months, turned over at 5 months, and sat alone at 10 months of age. His neurodevelopments were delayed since then; standing with support at 16 months, walk alone at 21 months of age. He used his first meaningful words at 2 yr of age, make phrases at 4 yr of age, and simple sentences at 5 yr of age. At the age of 5 yr, his mother noticed that he walked with a slow and broad-based gait, and all his movements were weak. However, he did not sought medical advice. His difficulty in walking was slowly aggravated, and he also had a difficulty in academic achievement recently. The patient has one female sibling. His father died at age 40 by car accident. There was no neurologic disorders and renal stone in his family. On admission, physical examination revealed minor dysmorphic features: long face, macrognathia, high arched palate, and large ear. Neurologic examination disclosed mild higher cortical dysfunction, dysarthria, upper limb and gait ataxia, hyperreflexia with bilateral extensor toe signs. Motor power and muscle tone were normal. The sensory examination disclosed no abnormalities except that vibration and position sense were impaired in lower extremities. All cranial nerve functions were intact. Optic fundi appeared normal. He had no tremor or involuntary movement. Neuropsychological evaluation revealed mild mental retardation on the K-WISC-III: full-scale intelligence quotient, 62; Verbal Scale intelligence quotient, 79; Performance Scale intelligence quotient; 47. Somatosensory evoked potential of posterior tibial nerve stimulation revealed no cortical waves (P1) suggestive of central conduction dysfunction through the posterior column of the spinal cord. However, spine magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) did not disclosed structural lesions in the spinal cord. Electromyography, nerve conduction study, and brain MRI were normal. Chromosome analysis and Fragile X mental retardation 1 (FMR1) gene studies are normal. Routine urinalysis and abdominal ultrasonography did not showed the evidence of urolithiasis. Cerebrospinal fluid examination, serum and cerebrospinal fluid lactate/pyruvate level, urine organic acid analysis, and plasma amino acid analysis were normal. Quantitative amino acid analysis of the urine disclosed increased excretion of cystine (1,345 µM/g Cr) and an excess of the dibasic amino acids; ornithine, lysine, and arginine (Fig. 1A). The oral cystine loading test resulted in elevation of plasma cystine levels (Fig. 1C). He was diagnosed non-type I cystinuria. His mother and sister were screened by quantitative amino acid analysis of the urine and showed variable degree of cystine and dibasic amino acids excretion (Fig. 1A).

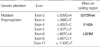

Mutation analysis of SLC3A1 and SLC7A9 genes was performed on genomic DNA samples, which were extracted from peripheral blood lymphocytes of the patient, his mother, and his sister. Amplification of individual exons of the two genes was performed using intronic primers obtained from the literature (7). Direct sequencing of entire coding region of SLC3A1 and SLC7A9 genes of the patient revealed both a G (normal) and A (mutant) at nucleotide 535 in exon 5, resulting in the presence of a Gly (codon GGA) at amino acid position 173 and a Arg (codon AGA) in heterozygote state (Fig. 1B). We identified the novel mutation, G173R and 6 known polymorphisms (Table 1). To confirm that G173R is not a polymorphism which could be found in normal control, we screened this mutation in 50 unrelated healthy Korean. This mutation was not present. The patients has only one mutation, G173R in SLC7A9 gene, therefore we screened for SLC3A1 mutations to ensure that no other mutations were missed. G173R was also detected in the genomic DNA of the patient's mother and sister.

Cystinuria is an inherited disorder of cystine and dibasic amino acids; ornithine, lysine, and arginine. This disorder is mainly expressed by the formation of cystine stones in the urinary tract. More than 80% of patients develop their first stone within the first 2 decades. On the other hand cystinuira has been occasionally described in association with a various neurological manifestations; mental retardation, muscular dystrophy, hypotonia and dwarfism, paroxysmal dyskinesia, migraine, subacute combined degeneration of the spinal cord, and cerebellar atrophy (4-6). Our patient is similar to these in that there is clinical evidence of posterior column, corticospinal tract involvement, and mental retardation.

Pathogenetic correlation between cystinuria and various neurological conditions is still undetermined, and a relevant explanation must be needed. If the amino acid transport systems of the brain closely resemble those of the kidney and gastrointestinal tract, one might expect that cystinuria could impaired brain functions (8, 9). Experimental results have demonstrated that transport systems for entry of cystine and cysteine into brain differ from those of kidney and intestine (10). It is unlikely that cystinuric patients are at risk of impaired cerebral functions because of difference in the amino acid transport systems of the nervous system (9). However, Scriver et al. (4) reported that homozygous cystinuria is statistically more prevalent in patients in mental hospitals than in the general population. This finding suggest that cystinuric patients are still at higher risk for impaired cerebral function.

Cystinuria is currently classified into three types according to the urinary phenotype in heterozygotes: type I (MIM220100), non-type I (MIM600918), and mixed. In non-type I heterozygotes showed a variable degree of urinary hyperexcretion of cystine and dibasic amino acids. Probands excreting more than 1,300 µM/g Cr are considered as phenotypically homozygote (11). This group include genetic homozygotes as well as compound heterozygotes. In type I cystinuria, there is no uptake of cystine by intestinal mucosal cells and there is no rise in serum cystine following an oral cystine load. In non-type I cystinuria, the intestinal transport of dibasic amino acids is disturbed, but not abrogated. There is some increment in plasma cystine following oral cystine load especially in patients which were previously classified as type III cystinuria by old classification scheme (9). In this patient, quantitative amino acid analysis disclosed increased urinary cystine excretion (1,345 µM/g Cr) within the range of phenotypic homozygote, and an excess of the dibasic amino acids; ornithine, lysine, and arginine (Fig. 1A). The oral cystine load resulted in increment of plasma cystine levels (Fig. 1C). His mother and sister also showed increased excretion of cystine and diabasic amino acids in urine (Fig. 1A), but less than those of the patient. Therefore, patient was diagnosed as non-type I cystinuria.

Despite the classification of the disease described above, a new scheme based only on genetic aspects has recently been proposed: Type A, caused by mutations in both alleles of SLC3A1; type B, caused by mutations in both alleles of SLC7A9; the possibility of type AB, with one mutation on each of the above genes (1). We screened the family with patient for gene mutation by sequencing of the SLC7A9 and SLC3A1 gene, and identified a new missence mutation G173R in SLC7A9 gene in heterozygote state. The present search for mutations covered the whole coding region and neighboring intron/exon boundaries. Despite careful analysis of the SLC3A1 and SLC7A9 genes, there are still a number of patients that lack mutations or display only heterozygosity (1).

Recently, two distinct recessive contiguous gene deletion syndrome, Hypotonia-Cystinuria Syndrome and 2p21 deletion syndrome, associated with type I cystinuria have been described (12, 13). In these contiguous gene deletion syndromes, various neurologic manifesations such as mental retardation, hypotonia, developmental delay, neonatal seizure, facial dysmorphism, and mitochondrial respiratory chain deficiencies were associated with type I cystinuria (14). This contiguous gene deletion is already known to disrupt the coding region of at least 4 genes (SLC3A1, PREPL, PPM1B and C2orf34). Deletion of SLC3A1 gene causes cytinuria, and loss of the other 3 genes are elucidated to contribute neurologic manifestations in these contiguous gene deletion syndromes. In this pedigree, patient's mother and sister did not showed clinical symptoms of cystinuria, but biochemical and molecular genetic data disclosed them as heterozygote of non-type I cystinuria. They also did not showed neurologic symptoms similar to those of the patient even though they had same G173R mutation in SLC7A9 gene. Although the neurologic manifestations of the patient probably are not to be caused by G173R mutation itself, it may be explained by unidentified other genes associated with SLC7A9 gene mutation including large gene deletion such as a contiguous gene deletion syndrome which may be transmitted to the patient from paternal side. Extensive genetic evaluation must be needed in the patient and his father to answer this question. Unfortunately, we could not investigate candidate genes in the patient and his father. Furthermore, we could not obtain proper clinical information of his father.

In conclusion, we identified a new mutation, G173R, in the exon 5 of SLC7A9 gene, in the patient with non-type I cystinuria associated with neurologic manifestations which presented as mental retardation and ataxia.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Pedigree of family with patient that carry mutation in SLC7A9, electropherograms of DNA sequencing for G173R mutation, and the result of oral cystine load in the patient. (A) Pedigree of family with patient; mutation in SLC7A9 and urine dibasic amino acid excretion. Urine amino acid excretion values for cystine (Cys), lysine (Lys), arginine (Arg), and ornithine (Orn) are expressed in µM/g creatinine (normal range: Cys, 30-130; Lys, 150-630; Arg, 30-110; Orn, 30-90). (B) Point mutation G173R (535G→A substitution) in SLC7A9 gene localized in exon 5. Patient's sequence has both G (normal) and A (mutant) at nucleotide 535, resulting in the presence of Gly (codon GGA) and Arg (codon AGA). (C) Changes in plasma cystine level after an oral L-cystine dihydrochloride load of 0.25 mM/kg body weight in the patient.

References

1. Font-Llitjos M, Jimenez-Vidal M, Bisceglia L, Di Perna M, de Sanctis L, Rousaud F, Zelante L, Palacin M, Nunes V. New insights into cystinuria: 40 new mutations, genotype-phenotype correlation, and digenic inheritance causing partial phenotype. J Med Genet. 2005. 42:58–68.

2. Calonge MJ, Gasparini P, Chillaron J, Chillon M, Galluci M, Rousaud F, Zelante L, Testar X, Dallapiccola B, Di Silverio F, Barcelo P, Estivill X, Zorano A, Nunes V, Palacin M. Cystinuria caused by mutations in rBAT, a gene involved in the transport of cystine. Nat Genet. 1994. 6:420–425.

3. Feliubadalo L, Font M, Purroy J, Rousaud F, Estivill X, Nunes V, Golomb E, Centola M, Aksentijevich I, Kreiss Y, Goldman B, Pras M, Kastner DM, Pras E, Gasparini P, Bisceglia L, Beccia E, Galluci M, de Sanctis L, Ponzone A, Rizzoni GF, Zelante L, Bassi MT, George AL, Palacin M. Non-type I cystinuria caused by nutations in SLC7A9, encording a subunit(bo, +AT) of rBAT. International Cystinuria Consortium. Nat Genet. 1999. 23:52–57.

4. Scriver CR, Whelan DT, Clow CL, Dallaire L. Cystinuria: increased prevalence in patients with mental disease. N Engl J Med. 1970. 283:783–786.

5. De Myer W, Gebhard RL. Subacute combined degeneration of the spinal cord with cystinuria. Neurology. 1975. 25:994–997.

6. Cavanagh NP, Bicknell J, Howard F. Cystinuria with mental retardation and paroxysmal dyskinesia in 2 brothers. Arch Dis Child. 1974. 49:662–664.

7. Font MA, Feliubadalo L, Estivill X, Nunes V, Golomb E, Kreiss Y, Pras E, Bisceglia L, d'Adamo AP, Zelante L, Gasparini P, Bassi MT, George AL Jr, Manzoni M, Riboni M, Ballabio A, Borsani G, Reig N, Fernandez E, Zorzano A, Bertran J, Palacin M. International Cystinuria Consortium. Functional analysis of mutations in SLC7A9, and genotype-phenotype correlation in non-Type I cystinuria. Hum Mol Genet. 2001. 10:305–316.

9. Bannai S. Transport of cystine and cysteine in mammalian cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1984. 779:289–306.

10. Hwang SM, Weiss S, Segal S. Uptake of L-[35S]cystine by isolated rat brain capillaries. J Neurochem. 1980. 35:417–424.

11. Guillen M, Corella D, Cabello ML, Garcia AM, Hernandez-Yago J. Reference values of urinary excretion of cystine and dibasic amino acids: classification of patients with cystinuria in the Valencian Community, Spain. Clin Biochem. 1999. 32:25–30.

12. Jaeken J, Martens K, Francois I, Eyskens F, Lecointre C, Derua R, Meulemans S, Slootstra JW, Waelkens E, de Zegher F, Creemers JW, Matthijs G. Deletion of PREPL, a gene encoding a putative serine oligopeptidase, in patients with hypotonia-cystinuria syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 2006. 78:38–51.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download