Abstract

Lactococcus lactis cremoris infections are very rare in humans. We experienced liver abscess and empyema due to L. lactis cremoris in an immunocompetent adult. A 42-yr-old man was admitted with fever and abdominal pain. Abdominal computed tomography (CT) revealed a liver abscess and chest CT showed loculated pleural effusion consistent with empyema. L. lactis cremoris was isolated from culture of the abscess material and blood. The patient was treated with pus drainage from liver abscess, video-assisted thoracoscopic decortications for empyema, and antibiotics including cefotaxime and levofloxacin. The patient was completely recovered with the treatment. To our knowledge, this is the first report of a L. lactis cremoris infection in Korea.

Lactococcus lactis cremoris is a facultative anaerobic gram positive coccus. This organism was once classified as streptococcus and was transferred to the genus Lactococcus in 1985 (1). It is recognized as a commensal organism of mucocutaneous surfaces of cattle, and is occasionally isolated from human mucocutaneous surface such as oropharynx, intestines, or vagina (2). This organism is used as additive in process of making dairy product. Although L. lactis cremoris is commonly considered to be non-pathogenic for immunocompetent adults, human infections have been noted (3-6). We report the first case of L. lactis cremoris infection in Korea, presenting with liver abscess and empyema.

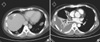

A 42-yr-old man was admitted to the Korean University Ansan Hospital with a 7-day history of fever and abdominal pain (2 March 2009). The patient had no past medical history, and denied a history of ingestion of raw milk products or exposure to any kind of cattle. On admission, his body temperature was 37.8℃ but he was hemodynamically stable. On chest auscultation, breathing sound was decreased on right lower lung field. Abdominal examination revealed tenderness on right upper quadrant area. A chest radiograph taken on admission showed multiple opacities on right upper lobe and right lower lobe, and bilateral small amount of pleural effusion. Abdominal computed tomography (CT) showed a low attenuating lesion 3.4 cm in size on the superior subcapsular portion of liver segment 8, which was suggestive of liver abscess (Fig. 1A). The abdominal CT also showed pleural effusion of both side but more serious on the right side. Initial laboratory results were as follows: white blood cell count, 17,160/µL; hemoglobin, 12.1 g/dL; aspartate aminotransferase, 34 IU/L; alanine aminotransferase, 41 IU/L alkaline phosphatase, 141 IU/L; gamma-glutamyl-transferase, 152 IU/L; C-reactive protein, 22.625 mg/L; and erythrocyte sedimentation rate over 120 mm/hr. Initially, the patient received 400 mg/day of intravenous (IV) ciprofloxacin and 1,500 mg/day of IV metronidazole with a clinical diagnosis of liver abscess. On day 2 of hospitalization, pus drainage was performed from liver abscess. Blood culture performed on admission and pus culture from liver abscess yielded growth of L. lactis cremoris. For the species identification, biological tests based on Rapid ID 32 strep Api kit (BioMérieux, Marcy-l'Etoile, France) were used. The isolate was sensitive to penicillin, cefotaxime, clindamycin, levofloxacin and vancomycin, and intermediately sensitive to erythromycin. On day 4 of hospitalization, following identification of the causative organism, ciprofloxacin was changed to 3,000 mg/day of IV cefotaxime. Thoracentesis was performed to verify the nature of fluid shown on abdominal CT scan images. Pleural fluid was turbid and straw-colored with a pH of 7.5, protein level of 4.9 g/dL, lactate dehydrogenase of 635 IU/L, and white blood cell count of 300/µL (74% neutrophil content). The protein ratio of pleural fluid versus serum was 0.64, consistent with exudate. Gram stain and culture of pleural fluid did not revealed organisms. In spite of antibiotic therapy and pus drainage from liver abscess, fever persisted and the patient did not recover clinically. On day 10 of hospitalization, a chest CT was taken to re-evaluate the status of lung and pleura. Pleural effusion and pleural thickening with enhancement were evident on the right side of lung with low density suggestive of empyema and necrotizing pneumonia (Fig. 1B). On day 15 of hospitalization, a video-assisted thoracoscopic decortication was performed for loculated empyema. Though the patient improved continuously after the operation, mild intermittent fever was noted. On day 22 of hospitalization, cefotaxime was switched to 500 mg/day of IV levofloxacin with suspicion of drug fever by cefotaxime. Subsequently, the fever subsided and the patient was discharged on day 31 of hospitalization.

Since the first case of infective endocarditis caused by L. lactis cremoris, formerly known as Streptococcus cremoris, was reported in 1955 (7), there have been 13 case reports of human infections, most commonly infective endocarditis (6-10). Two cases of liver abscess (6, 11) and one case of necrotizing pneumonitis accompanied by empyema have also been reported (12). To date, however, there have been no reports from Korea. Moreover, this is the first report of an infection, in which liver abscess and empyema occurred concurrently by L. lactis cremoris.

There are five species in the genus Lactococcus; L. lactis, L. garvieae, L. piscium, L. plantarum, and L. raffinolactis. Among the species of L. lactis, L. lactis ssp. lactis, L. lactic ssp. cremoris, and L. lactis ssp. lactis biovar diacetylactis are used for the production of fermentated dairy products. L. lactis cremoris is particularly preferred for the production of chedar cheese (13). As a result, exposure to unpasteurized dairy products has been suggested as a risk factor of L. lactis cremoris infection. Of the previously reported cases, six have the history of exposure to unpasteurized dairy products (3). While many bacteria commonly used in food preparation are killed during digestion, it is known that lactococcus remains viable after transit through the gastrointestinal tract (14). This is thought to be the mechanism of L. lactis cremoris infection in humans.

In our case, the patient denied a history of ingestion of raw milk products or exposure to any kind of cattle, and did not have any past history of chronic diseases. Although we did not determine the origin of L. lactis cremoris in our case, we assume that the patient might have acquired the disease through ingestion some food colonized with L. lactis cremoris.

In this case, L. lactis cremoris was isolated in both blood and from pus draining from liver abscess. As a result, the organism was considered to be a true pathogen of liver abscess and empyema, although it is a rare infectious disease in humans. Our failure to isolate any organism from pleural fluid may have reflected the effectiveness of antibiotic treatment.

Standards for treatment of L. lactis cremoris infection have not been well-established. In the previously reported cases, antibiotic regimens based on the result of susceptibility test were the mainstay of treatment, and penicillin or third-generation cephalosporin was chosen most commonly (5, 15, 16). In this case, we chose cefotaxime based on the result of susceptibility testing. Response to cefotaxime seemed to be poor, perhaps due to the remaining empyema; consistent with this suggestion, fever subsided and clinical improvement was observed after the drainage and decortication of pleural effusion.

This is the first report of a L. lactis cremoris infection in Korea and L. lactis cremoris should be considered in the differential diagnosis of in liver abscess or empyema even if exposure to raw milk products is not evident.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan images. (A) An abdominal CT scan showed a low attenuating lesion 3.4 cm in size on the superior subcapsular portion of liver segment 8, which was suggestive of liver abscess (arrow). (B) A chest CT scan showed pleural effusion and pleural thickening with enhancement on right side of lung with low density, which was suggestive of empyema and necrotizing pneumonia (arrow).

References

1. Schleifer KH, Kraus J, Dvorak C, Kilpper-Balz R, Collins MD, Fischer W. Transfer of Streptococcus lactis and related streptococci to the genus Lactococcus gen. nov. Syst Appl Microbiol. 1985. 6:183–195.

3. Davies J, Burkitt MD, Watson A. Ascending cholangitis presenting with Lactococcus lactis cremoris bacteraemia: a case report. J Med Case Reports. 2009. 3:3.

4. Mofredj A, Beldjoudi S, Farouj N. Purulent pleurisy due to lactococcus lactis cremoris. Rev Mal Respir. 2006. 23:485–486.

5. Koyuncu M, Acuner IC, Uyar M. Deep neck infection due to Lactococcus lactis cremoris: a case report. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2005. 262:719–721.

6. Antolin J, Ciguenza R, Saluena I, Vazquez E, Hernandez J, Espinos D. Liver abscess caused by Lactococcus lactis cremoris: a new pathogen. Scand J Infect Dis. 2004. 36:490–491.

7. Wood HF, Jacobs K, McCARTY M. Streptococcus lactis isolated from a patient with subacute bacterial endocarditis. Am J Med. 1955. 18:345–347.

8. Pellizzer G, Benedetti P, Biavasco F, Manfrin V, Franzetti M, Scagnelli M, Scarparo C, de Lalla F. Bacterial endocarditis due to Lactococcus lactis subsp. cremoris: case report. Clin Microbiol Infect. 1996. 2:230–232.

9. Mannion PT, Rothburn MM. Diagnosis of bacterial endocarditis caused by Streptococcus lactis and assisted by immunoblotting of serum antibodies. J Infect. 1990. 21:317–318.

10. Galinski J, Zelawska B. Endocarditis lenta caused by Streptococcus lactis. Pol Tyg Lek. 1966. 21:1282–1283.

11. Nakarai T, Morita K, Nojiri Y, Nei J, Kawamori Y. Liver abscess due to Lactococcus lactis cremoris. Pediatr Int. 2000. 42:699–701.

12. Torre D, Sampietro C, Fiori GP, Luzzaro F. Necrotizing pneumonitis and empyema caused by Streptococcus cremoris from milk. Scand J Infect Dis. 1990. 22:221–222.

13. Basaran P, Basaran N, Cakir I. Molecular differentiation of Lactococcus lactis subspecies lactis and cremoris strains by ribotyping and site specific-PCR. Curr Microbiol. 2001. 42:45–48.

14. Drouault S, Corthier G, Ehrlich SD, Renault P. Survival, physiology, and lysis of Lactococcus lactis in the digestive tract. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999. 65:4881–4886.

15. Akhaddar A, El Mostarchid B, Gazzaz M, Boucetta M. Cerebellar abscess due to Lactococcus lactis. A new pathogen. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2002. 144:305–306.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download