Abstract

Hepatitis A virus (HAV) infection is generally a self-limited disease, but the infection in adults can be serious, to be often complicated by acute kidney injury (AKI) and rarely by virus-associated hemophagocytic syndrome (VAHS). Our patient, a 48-yr-old man, was diagnosed with HAV infection complicated by dialysis-dependent AKI. His kidney biopsy showed acute tubulointerstitial nephritis with massive infiltration of activated macrophages and T cells, and he progressively demonstrated features of VAHS. With hemodialysis and steroid treatment, he was successfully recovered.

Acute kidney injury often complicates hepatitis A virus (HAV) infection. An incidence between 3% and 5.7% has been reported in retrospective studies (1, 2), and both acute tubular necrosis (ATN) and acute tubulointerstitial nephritis (ATIN) have been reported (1, 3). Hemophagocytic syndrome, a very rare complication of HAV infection, is characterized by abnormal activation of macrophages with subsequent hemophagocytosis, splenomegaly, fever, and cytopenia (4); hemophagocytic syndrome can also be complicated by multiple organ failure. Our patient developed dialysis-dependent acute kidney injury (AKI) secondary to HAV infection and progressively showed features of virus-associated hemophagocytic syndrome (VAHS), which was successfully treated by steroids. We suggest a possible link between ATIN that was characterized by macrophage and T cell infiltration and development of VAHS caused by HAV infection.

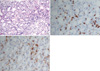

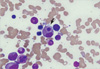

A 48-yr-old man was transferred to our hospital with the diagnosis of AKI due to HAV infection requiring dialysis on June 4, 2009. He had been admitted to another hospital with general weakness and jaundice. The initial laboratory examination revealed the presence of IgM anti-HAV antibody, aspartate transaminase 1212 (5-45) IU/L, alanine transaminase 2,462 (10-40) IU/L, total bilirubin 7.8 (0.3-1.4) mg/dL, direct bilirubin 6.2 (0-0.4) mg/dL, gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase 102 (0-39) IU/L, hemoglobin 14.4 (13.1-17.2) g/dL, white blood cell count 14,700 (4,500-11,000)/µL, and platelet count 163,000 (150,000-400,000)/µL. The blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and creatinine were 43.6 (7-20) and 9.3 (0.7-1.3) mg/dL, respectively, and hemodialysis was started. He developed fever on day 4 before transfer and vancomycin was administered for possible catheter-related bacteremia. Upon presentation to our hospital, he was markedly jaundiced, and complained of weakness, fever, and rash. The vital signs were as follows: blood pressure, 200/100 mmHg; pulse rate, 108 beats/min; respiratory rate, 24/min; and body temperature, 38.1℃. There were no palpable lymph nodes. The BUN and creatinine levels rose to 85 and 15.2 mg/dL, respectively, and the total bilirubin level progressively increased to 21.8 mg/dL, with a normal prothrombin time. Viral markers, including Ebstein-Barr virus (EBV) and cytomegalovirus, were negative; HAV was positive. Urinalysis showed dark-colored urine with 2+ bilirubin, a trace of blood, and 1+ proteinuria. A 24-hr urine test revealed albuminuria (197.2 mg). The daily urine output was maintained at 1,500-2,000 mL with furosemide. A chest roentgenogram initially showed pulmonary congestion with a bilateral pleural effusion that was improved by furosemide. Abdominal ultrasonography showed normal sized kidneys with increased echogenecity and splenomegaly. On the 3rd hospital day, a kidney biopsy was performed and showed a diffusely edematous interstitium with infiltration of inflammatory cells and severely damaged tubules, findings which were compatible with ATIN. An immunohistochemical study identified the infiltrating cells as predominantly CD3+ T cells and CD68+ activated macrophages (Fig. 1). The glomeruli were relatively well-preserved. On the 8th hospital day, consolidation in both upper lobes developed. All microbiological culture studies were negative and no endobronchial lesions were detected. Despite catheter exchange and empirical antibiotics, a high fever, consolidation, and rash persisted. With hemodialysis and supportive care, liver and kidney dysfunction gradually improved, while anemia worsened and leucopenia and thrombocytopenia developed; the hemoglobin was 7.4 g/dL (hematocrit, 22.2%), the absolute neutrophil count was 130/µL, and the platelet count was 141,000/µL. Granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) was given. A bone marrow biopsy revealed a normocellular marrow with occasional hemophagocytosis (Fig. 2); there was no evidence of malignancy. The ferritin level was 2678 (17-390) ng/mL, the triglycerides were 493 (55-327) mg/dL, and the fibrinogen was 557 (225-457) mg/dL. VAHS was highly suspected and steroids were added to the treatment regimen. Upon steroid treatment, the fever, rash, and bilateral consolidation rapidly subsided. Hemodialysis was stopped after 13 dialysis sessions and renal function remained stable with a serum creatinine level of 1.7 mg/dL. He was discharged on a steroid taper in the outpatient clinic. The creatinine level declined to 1.3 mg/dL about 1 month later.

HAV infection is generally self-limiting, but it can cause serious morbidity, such as AKI and occasional mortality (3). Although not frequently reported, HAV infection is also associated with hematologic complications, including VAHS (5). Hemophagocytic syndrome (HPS) is a rare, but potentially fatal disease. HPS is characterized by impaired function of NK and cytotoxic T cells, resulting in uncontrolled and ineffective immune activation, and leading to cellular damage as well as proliferation of benign macrophages with hemophagocytosis (6, 7). HPS is divided into primary and secondary forms. EBV is the most common triggering agent and herpes infection is responsible for >50% of secondary VAHS cases (8). HAV is known to be associated with VAHS, but only 14 cases have been reported (4, 9).

The following diagnostic guidelines for VAHS were first proposed in 1991 by the Histiocyte Society and updated in 2004 (10): 1) fever, 2) splenomegaly, 3) cytopenia (≥2 of 3 lineages), 4) hypertriglyceridemia (≥265 mg/dL) and/or hypofibrinogenemia (≤150 mg/dL), 5) hemophagocytosis in the bone marrow, spleen, or lymph nodes, without evidence of malignancy, 6) low or absent NK cell cytotoxicity, 7) hyperferritinemia (≥500 ng/mL), and 8) elevated soluble CD 25 (IL-2Rα chain ≥2,400 IU/mL). HPS is defined by the presence of 5 of the 8 criteria. Fever and splenomegaly are main clinical features and jaundice, hepatomegaly, lymphadenopathy, rash, and lung infiltration are also common (7). Our patient met 6 of the 8 criteria (fever, splenomegaly, cytopenia, hypertriglyceridemia, hemophagocytosis in BM, and hyperferritinemia). The diagnosis of VAHS was delayed until the development of marked cytopenia in the current case. On kidney biopsy, interstitial mononuclear cells were identified to be mostly T lymphocytes and macrophages. Although an occasional association of HAV with ATN or ATIN has been reported, the precise pathogenic mechanisms are unknown, partly due to the rarity of kidney biopsies or immunohistochemical studies. HPS is also associated with diverse renal manifestations. Karras et al. (8) suggested that the possible mechanism of AKI in HPS was direct toxicity of pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-6 and TNF-α) on kidney tubular cells. In our case of pathologically-confirmed ATIN due to HAV infection in which the hospital course was complicated by HPS, we observed massive kidney infiltration of activated macrophages and T cells. The role of macrophages or T cells in an animal model of AKI is well-known and is thought to contribute to renal dysfunction. However, whether the kidney infiltration in this case was specific to ATIN caused by HAV or was secondary to concurrent VAHS is unknown. The number of interstitial CD68+ macrophages or CD3+ T cells in the current case was much higher than those of other kidney biopsy specimens from patients with HAV complicated by AKI (data not shown). Therefore, massive interstitial infiltration of macrophages and T cells in the kidney is likely to be associated with HPS.

Even though there are no randomized controlled trials addressing the treatment modalities for this rare HPS, patients are often started on corticosteroids with or without intravenous gamma-globulin, as well as supportive care and treatment for the underlying infection. In addition, cytotoxic drugs, such as etoposide and cyclosporine, have been used and recent reports support the safety of G-CSF in patients with severe neutropenia. Bone marrow transplantation can also save a life in severe cases. G-CSF and steroids were administered to our patient and clinical features, such as cytopenia, fever, rash, and pulmonary infiltrates, recovered rapidly.

Herein we have reported a case of ATIN secondary to HAV infection characterized by kidney infiltration of activated macrophages and T cells in which the clinical course was complicated by VAHS, suggesting a possible link between macrophage- and T cell-predominant ATIN and VAHS caused by HAV infection. In addition, when unusual symptoms, such as persistent fever and cytopenia, develop in patients with HAV infection, concurrent HPS should be considered.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Histopathological microscopy of the kidney biopsy. (A) Under light microscopy, diffuse edematous interstitium with damaged tubules and infiltration of inflammatory cells are shown. (H&E stain, ×100) (B, C) Immunohistochemistry. Diffuse and patchy interstitial infiltration of CD3- (B) and CD68-positive (C) cells is noted (×200).

References

1. Kim SH, Yoon HE, Kim YK, Kim JY, Choi BS, Choi YJ, Kim YO, Kim YS, Bang BK, Yang CW. Acute hepatitis A-associated acute renal failure in adults. Nephron Clin Pract. 2008. 109:c127–c132.

2. Song KS, Kim MJ, Jang CS, Jung HS, Lee HH, Kwon OS, Kim YS, Choi DJ, Kim JH, Ha SY. Clinical features of acute viral hepatitis A complicated with acute renal failure. Korean J Hepatol. 2007. 13:166–173.

3. Kim HW, Yu MH, Lee JH, Chang JW, Yang WS, Kim SB, Lee SK, Park JS, Park SK. Experiences with acute kidney injury complicating non-fulminant hepatitis A. Nephrology (Carlton). 2008. 13:451–458.

4. Tuon FF, Gomes VS, Amato VS, Graf ME, Fonseca GH, Lazari C, Nicodemo AC. Hemophagocytic syndrome associated with hepatitis A: case report and literature review. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2008. 50:123–127.

5. Chatzimichael A, Schoina M, Arvanitidou V, Ramatani A, Mantadakis E. Hematologic complications of hepatitis A: another reason for implementation of anti-HAV vaccination. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2008. 30:562.

7. Rouphael NG, Talati NJ, Vaughan C, Cunningham K, Moreira R, Gould C. Infections associated with haemophagocytic syndrome. Lancet Infect Dis. 2007. 7:814–822.

8. Karras A. What nephrologists need to know about hemophagocytic syndrome. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2009. 5:329–336.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download