Abstract

The authors report a case of acute kidney injury (AKI) resulting from menstruation-related disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) in an adenomyosis patient. A 40-yr-old woman who had received gonadotropin for ovulation induction therapy presented with anuria and an elevated serum creatinine level. Her medical history showed primary infertility with diffuse adenomyosis. On admission, her pregnancy test was negative and her menstrual cycle had started 1 day previously. Laboratory data were consistent with DIC, and it was believed to be related to myometrial injury resulting from heavy intramyometrial menstrual flow. Gonadotropin is considered to play an important role in the development of fulminant DIC. This rare case suggests that physicians should be aware that gonadotropin may provoke fulminant DIC in women with adenomyosis.

Disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) is characterized by the systemic intravascular activation of coagulation (1). DIC can contribute to acute kidney injury (AKI) and other multiorgan failures due to the widespread deposition of fibrin in the circulation and the consequent compromise of blood supply to various organs. DIC is associated with various gyneco-obstetric conditions, such as, uterine leiomyoma and abruptio placenta. However, DIC associated with adenomyosis is uncommon. A literature review revealed only one report of DIC development during menstruation in an adenomyosis patient (2). However, in this previously reported case, AKI and other organ failures were not observed.

We here present a case of AKI which resulting from menstruation-related DIC that was probably provoked by gonadotropin administration.

A 40-yr-old woman who had experience of primary infertility with diffuse adenomyosis (Fig. 1) presented with anuria and an elevated serum creatinine (SCr) level at the Emergency Medicine Department on May 28, 2008. She had a history of two cycles of in vitro fertilization (IVF) at an infertility clinic, and the second cycle was performed 3 weeks prior to admission. Each cycle of IVF was treated with long protocol of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonist. For ovulation induction, daily 500 IU of human menopausal gonadotropin was administered on menstrual cycle days 3-15 and 5,000 IU of human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) was administered on day 16, at 18 mm of leading follicles size. Ovum aspiration was performed at 36 hr after hCG injection. Five and nine oocytes were obtained at first and second cycle, respectively. Daily 50 mg of progesterone and once every three days 1,000 IU of hCG were administered for luteal support. The objective evidences of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome were not present on the day of ovum collection and 7 days later.

On admission, her blood urea nitrogen (BUN) level was 41.1 mg/dL, and her SCr level was 3.5 md/dL. An examination of medical records revealed a baseline SCr level of 0.8 mg/dL, and a physical examination revealed an extremely enlarged uterus, which was palpable at the level of the umbilicus. Her pregnancy test was negative and her menstrual cycle had started 1 day before admission. Her vital signs were stable, and renal ultrasonography excluded an acute ureteral obstruction.

Laboratory testing showed the following: white blood cell (WBC) count 30.07×109/L, hemoglobin level (Hb) 10.0 g/dL, hematocrit (Hct) 29.6%, platelet count 39×109/L, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) 7,914 IU/L, aspartate aminotransferase (AST) 329 IU/L, alanine aminotransferase (ALT) 92 IU/L, alkaline phosphatase (ALP) 180 IU/L, total bilirubin 2.72 mg/dL, and cancer antigen 125 (CA125) 16,684 U/mL. A peripheral blood smear revealed numerous schistocytes.

A coagulation test revealed the characteristics of DIC (1). Her laboratory values were as follows: prothrombin time (PT) 24.6 sec (normally 11.0 to 14.1 sec), prothrombin time-internationalized ratio (PT-INR) 2.25, activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) 58.2 sec (normally 30 to 44 sec), fibrinogen level 88 mg/dL, D-dimer level 19.3 µg/mL, and antithrombin III level 74%. She had no known factor predisposing DIC, such as, infection or a malignancy.

Urinalysis revealed numerous red and white blood cells, but her urine and blood cultures were negative. Serologies for antinuclear antibodies (ANA), antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA), cryoglobulins, hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), anti-glomerular basement membrane antibodies (Anti-GBM), and antistreptococcal antibodies were all negative. Complement levels were within the normal range. Furthermore, both serum and urine protein electrophoresis failed to demonstrate a monoclonal component, and her computed tomographic renal scan was unremarkable.

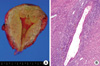

Under a diagnosis of AKI resulting from unexplained DIC, the patient was treated with 0.9% sodium chloride solution, fresh frozen plasma, and platelet concentrates. However, despite treatment, the patient required continuous renal replacement therapy and therapeutic plasmapheresis due to progressive AKI and multiorgan failures. The menstrual phase was terminated on the fourth hospital day, and coagulation test findings then gradually improved. Her SCr level peaked on the 14th hospital day, and reached a nadir of 1.1 mg/dL on 30th hospital day. The patient was treated with GnRH agonist for 3 months, and then underwent hysterectomy on September 28, 2008. Pathological findings confirmed diffuse adenomyosis (Fig. 2).

Adenomyosis is a benign gynecological condition that is characterized by the presence of endometrial glands and stroma within the myometrium (3). In adenomyosis patients, AKI is usually caused by obstructive uropathy. Furthermore, an uterus affected by adenomyosis can enlarge to that expected on the 12th gestational week. In addition, adenomyosis is frequently associated with other uterine conditions, such as, leiomyoma (35-55%) or pelvic endometriosis (5-20%). Thus, the differential diagnosis of AKI should include obstructive uropathy, either caused by adenomyosis per se or by coexisting conditions, such as, a bulky leiomyoma or ureteral endometriosis.

In our case, renal ultrasonography excluded obstructive uropathy and laboratory data were consistent with AKI resulting from unexplained DIC. Accordingly, because she had no known factor predisposing DIC, menstruation-related DIC was suspected. Nakamura et al. reported the first case of DIC development during menstruation in an adenomyosis patient, and proposed a myometrial injury mechanism (2). We agree that myometrial injury resulting from heavy intramyometrial menstrual flow might activate the tissue factor coagulation pathway. However, fulminant DIC with AKI and other organ failures was not observed in their case.

We believe that gonadotropin played an important role in the development of fulminant DIC in our patient. Adenomyosis is often accompanied by adjacent myometrial smooth muscle hyperplasia, and adenomyotic tissue and myometrium are known to express estrogen and progesterone receptors (4, 5). Therefore, gonadotropin, which stimulates ovarian steroidogenesis, can promote the proliferation of adenomyotic tissue and adjacent myometrium, and thus, contribute to extensive myometrial injury during menstruation.

In addition, gonadotropin can provoke fulminant DIC via another mechanism. The myometrium is a significant source of tissue factor, which plays a key role in the initiation of coagulation (6). Furthermore, because tissue factor expression is also under the control of ovarian steroids (7), gonadotropin might contribute to the overexpression of tissue factor and activation of the coagulation cascade.

Adenomyosis can be confirmed only by pathologic examinations of hysterectomy specimens. However, recent studies have shown that MRI can accurately diagnose adenomyosis, and that it has a sensitivity and specificity that range from 86 to 100% (8). Furthermore, it appears that non-enhanced T2-weighted imaging is useful in the setting of AKI because of the risk of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis.

Like endometriosis, adenomyosis is a hormone-sensitive disease (9). Moreover, because the growth of adenomyotic tissue is associated with a hyperestrogenic state, hormonal therapy based on progesterones, oral contraceptive pills, anti-estrogens, or GnRH agonists could be useful. Our patient did not experience recurrent DIC after GnRH agonist treatment, which creates a hypoestrogenic environment. Thus, hormonal therapy might prevent further DIC aggravation, especially when hysterectomy is contraindicated in patients with multiple organ failures.

Adenomyosis is a common disorder that present in 20-35% of women undergoing hysterectomy for benign gynecological disorders. Presenting symptoms include an enlarged uterus, menorrhagia, and dysmenorrhea. Infertility is a less frequent complaint because the majority of cases are diagnosed in their fourth and fifth decades of life. However, because an increasing number of women now postpone their first pregnancy until the late thirties, adenomyosis is being encountered more frequently in infertility clinics (10).

Summarizing, we experienced a case of adenomyosis in a 40-yr-old woman who developed AKI due to menstruation-related DIC development after gonadotropin administration. Physicians should be aware that gonadotropin can provoke fulminant DIC in women with adenomyosis.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

T2-weighted MRI scan showing extensive adenomyosis involvement. Low signal intensity areas involving most of the uterus demonstrated diffuse thickening of the junctional zone. Punctuate high signal foci represent islands of ectopic endometrial tissue or microhemorrhage (arrows).

Fig. 2

Pathological findings of hysterectomized uterus. (A) Gross appearance of adenomyosis. Note coarsely trabeculated, diffusely hypertrophied myometrium stippled with foci of ectopic endometrium. (B) Hematoxylin and eosin-stained section of uterus, showing endometrial glands and stroma surrounded by hypertrophied myometrium. Occasional hemosiderin-laden macrophages were also observed. Magnification, ×100.

References

1. Taylor FB Jr, Toh CH, Hoots WK, Wada H, Levi M. Scientific Subcommittee on Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation (DIC) of the International Society of Thrombosis and Haemostasis (ISTH). Towards definition, clinical and laboratory criteria, and scoring system for disseminated intravascular coagulation. Thromb Haemost. 2001. 86:1327–1330.

2. Nakamura Y, Kawamura N, Ishiko O, Ogita S. Acute disseminated intravascular coagulation developed during menstruation in an adenomyosis patient. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2002. 267:110–112.

3. Azziz R. Adenomyosis: current perspectives. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 1989. 16:221–235.

4. Noe M, Kunz G, Herbertz M, Mall G, Leyendecker G. The cyclic pattern of immunohistochemical expression of oestrogen and progesterone receptors in human myometrial and endometrial layers: characterization of the endometrial-subendometrial unit. Hum Reprod. 1999. 14:190–197.

5. Leyendecker G, Herbertz M, Kunz G, Mall G. Endometriosis results from the dislocation of basal endometrium. Hum Reprod. 2002. 17:2725–2736.

6. Drake TA, Morrissey JH, Edgington TS. Selective cellular expression of tissue factor in human tissues. Am J Pathol. 1989. 134:1087–1097.

7. Lockwood CJ, Nemerson Y, Krikun G, Hausknecht V, Markiewicz L, Alvarez M, Guller S, Schatz F. Steroid-modulated stromal cell tissue factor expression: a model for the regulation of endometrial hemostasis and menstruation. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1993. 77:1014–1019.

8. Reinhold C, Tafazoli F, Mehio A, Wang L, Atri M, Siegelman ES, Rohoman L. Uterine adenomyosis: endovaginal US and MR imaging features with histopathologic correlation. Radiographics. 1999. 19:S147–S160.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download