INTRODUCTION

Traumatic spinal cord transection is uncommon. In a study of 62 patients with spinal cord injuring who underwent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), 7 had cord transections (1). In contrast to children in who closed spinal cord trauma may occur in the absence of skeletal injury, most cord injuries in adults are associated with major musculoskeletal injuries, such as vertebral fractures and/or dislocations (2-6). In the subaxial cervical spine, hyperextension injuries without facet dislocations are well known as central cord syndromes, but cervical cord transection has not been described in the literature (7-10).

We report a patient with a cervical cord transection in the absence of a vertebral dislocation secondary to air bag deployment without the use of a seat belt and discuss the mechanism of this type of injury.

CASE REPORT

A 33-yr-old male was admitted through the emergency room with neck pain, and loss of sensation and inability to move all four extremities. He had crashed his car into the post of a traffic signal, was not wearing a seat belt, and the front air bag deployed. On neurologic examination, the patient had flaccid paralysis of all four extremities, a sensory level at C4, no sphincter control or rectal tone, an absent anal wink, no sacral sparing, and a positive bulbocavernosus reflex. He was fully alert with mild hypotension (systolic arterial pressure <100 mm Hg). No gross wounds were observed on close inspection of the entire body.

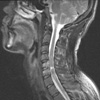

Plain radiographic evaluation of his cervical spine showed C5, C6 wedge compression fractures and minimal C5 retrolisthesis on C6 (Fig. 1). A computed tomographic (CT) scan also demonstrated C5, C6 vertebral body vertical fractures with laminar fractures, and a C3 spinous process fracture (Fig. 2). The fractured C5 lamina was depressed into the spinal canal through the lamina-facet junctions. The C5/6 facet joints were intact. A MRI revealed a linear area of abnormal signal intensity running horizontally through the spinal cord at the C5-6 disc space level, which was thought to represent a spinal cord transaction (Fig. 3). The patient had no brain, thoracic, or abdominal abnormalities on plain films and CT scans.

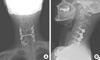

The patient underwent surgery via a posterior approach 5 days after his injury. A C5 laminectomy with a posterior fusion and lateral mass screw fixation at the C4-C7 levels was performed (Fig. 4). During this procedure, disruption of the C4-5 supraspinous and interspinous ligaments were noted, but the facet joint capsules were intact at the C4-C7 levels in the operative field. He was transferred to the rehabilitation department 1 month post-operatively and no neurologic improvement had been observed 4 months after the injury.

DISCUSSION

There have been no reports of traumatic spinal cord transections in adults other than fracture-dislocation injuries in the subaxial spine. Although Berlot et al. (11) described a delayed post-traumatic cervical cord transection in a spinal cord injury without radiologic abnormalities (SCIWORA), the initial MRI revealed only focal swelling of the spinal cord and several patch areas of cord contusions; indeed, an initial incomplete lesion may have progressed to transection in the absence of fixation.

Our patient's injury appeared to have occurred when his torso overrode the air bag, which resulted in acute hyperextension of the cervical spine. This potential mechanism has been shown in crash simulations using human cadavers and dummies positioned opposite airbags when unbelted (12). But in such simulations, the velocities were between 32 and 48 km/hr. The velocity in our patient was more than 60 km/hr, so a more extreme hyperextension injury may have occurred. During the episode of hyperextension, rupture of the anterior longitudinal ligament and the disc caused marked backward displacement of the C5 vertebral body against the cord (13). Also, our patient had a C5 laminar fracture, which may have exacerbated the hyperextension and posterior displacement. Although there was no facet disruption, this circumstance could result in a C5/6 spinal cord transection. Because the spine returned to its normal position by the elastic recoil of the vertebral muscles when the head is in the neutral position or in flexion (14), subtle C5 retrolisthesis on C6 was just observed in post-traumatic radiologic studies.

The above mechanism of injury could explain the cord transection and injuries involving the posterior vertebral column. However, C5, C6 vertebral body fractures are unresolved. According to Allen's classification of subaxial cervical fractures and dislocations (15), our patent's injury was a distractive extension stage 2 lesion. In this type of injury, however, there was no co-existing vertical fracture centrum. Therefore, we propose the hypothesis that during the initial short moment of the collision, the airbag was just in contact with the torso, but not with the face of the patient. As a result, compressive flexion force interacted at the cervical spine, resulting in C5, C6 vertebral body fractures. This hypothesized mechanism is summarized in Fig. 5.

The course of treatment in this patient is of less interest than the proposed mechanism of injury. Distractive extension stage 2 lesions must be surgically stabilized, usually with an anterior approach. However, in the presence of cord involvement by laminar fragments with preservation of lordotic sagittal alignment, a posterior approach is also useful (16). In this case report, the patient underwent a posterior fusion and lateral mass screw fixation. Four months after the operation, no cervical instability was observed while the patient ambulated in a wheelchair. Although there is a constant search for ways and means to enhance recovery of spinal cord injury, this patient's prognosis is very poor. According to data of the Model Spinal Cord Injury Systems (17), 94.4% of patients with neurological complete spinal cord injuries remained so at the 5-yr post-injury evaluation. Nevertheless, Kirshblum et al. reported approximately 20% showed some improvement in motor power and neurologic level of injury from year 1 to year 5 (18). Therefore medical rehabilitation service should be provided sufficiently and continuously for the sake of this patient's recovery.

Although this report describes just a single case of spinal cord transection by motor vehicle accident, it emphasizes the importance of proper use of seat belts especially in the circumstance of airbag deployment. The authors' proposed hyperflexion-hyperextension mechanism can result in significant neurologic deficits, but subtle radiographic abnormalities might be seen on plain films. So clinicians in emergency centers should have the possibility of cord transection in the acutely injured patient in mind because it is important for both prognostic and therapeutic reasons.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download