Abstract

We evaluated the utility and feasibility of customizing Asthma Control Test (ACT) items to generate a Korean Asthma Control Test (KACT) specific for Korean patients. We surveyed 392 asthma patients with 19 items, selected to reflect the Korean sociocultural context. Guideline ratings were integrated with the evaluations of specialists (i.e., using both guide base rating together with specialist's rating), and items with the greatest discriminating validity were identified. Stepwise regression methods were used to select items. KACT scale scores showed significant differences between the asthma control ratings generated by integrating ratings (r=0.77, P<0.001), by specialist's evaluations (r=0.54, P<0.001), or by FEV1 percent predicted (r=0.39, P<0.001). Specialist's and guideline ratings detected 56% and 48.6% of patients with well-controlled asthma, respectively. However, the integrated ratings indicated that only 34.3% of the patients in the test sample were well controlled. The overall agreement between KACT and the integrated rating ranged from 45% to 78%, depending on the cut-off points used. It is possible to formulate a valid, useful country-specific diagnostic tool for the assessment of asthma patients based on the original ACT that reflect differences in sociocultural context.

Asthma control cannot be accurately assessed by any single testing parameter (1, 2). For example, the pulmonary function test reveals the status of a patient at only a single point in time and does not reflect real-life conditions (3, 4). The assessment of asthma control based solely on patient symptoms is also inaccurate. Rabe et al. (5) reported that 32-49% of patients with severe asthma symptoms, and 39-70% of patients with moderate asthma symptoms, perceived their asthma as well controlled. The fact that patients are likely to overestimate their level of control may cause physicians to underestimate their patients' symptoms, and therefore under-treat their asthma (6). Exact assessments of patient asthma control levels are required for proper treatment (7).

Multidimensional assessment using various factors is necessary for precise assessment of asthma control. However, it is difficult for primary care physicians to practice multidimensional assessment in real-life clinical settings, especially in many Asian countries, because of time constraints and shortages of resources, such as spirometry and trained nurses. Several years ago, an easy-to-use, patient-based five-item Asthma Control Test (ACT; QualityMetric, Lincoln RI, USA) was developed (8). In a longitudinal study on asthma patients who were not under the care of asthma specialists, ACT was demonstrated to be a reliable, valid and responsive tool for assessing changes in patients' asthma control (9).

Asthma symptoms and aggravating factors vary among countries (10). More importantly, the same symptoms may be described differently, according to culture (11), level of medical knowledge and education (12-14), patient age (15) and social recognition of asthma (16). Therefore, customization of the ACT items might accomplish more precise assessment of asthma control. Kwon et al. (17) reported that Korean version of the ACT was a reliable and valid tool for measuring asthma control, but they looked at just correlation between ACT and health-related quality of life (HRQL) only. A patients' HRQL is not fully accounted for by objective measures, so there is possibility that Korean version of ACT may not be strongly validated (18).

Because of objective criteria for evaluating asthma symptoms are lacking, asthma specialists mainly assess asthma control according to their clinical experience. Therefore, using both guideline-based ratings together with specialist's ratings (i.e., integrating rating), might be a reasonable way to assess the level of asthma control. An integrated rating system may help in the selection of more accurate ACT items with higher discrimination and validity. The objective of this study was to find items that would be more useful for assessing the level of asthma control in Korean asthma patients based on original ACT items.

In this cross-sectional study, a working group of eight leading asthma specialists was convened to select and develop customized items for a Korean Asthma Control Test (KACT), starting with the original ACT items (8). Because Koreans tend to have especially sensitive emotional responses to medications, the working group decided to add items related to drug efficacy. In total, 19 items were selected based on original ACT items to reflect a Korean cultural context (19) (Table 1).

We selected study subjects from patients population of the eight asthma specialists who formed the working group of this study. All participants were older than 16 yr of age and had no other respiratory diseases. Diagnosis of asthma was confirmed by pulmonary function test (e.g. positive bronchodilator or methacholine challenge test). During a routine, previously scheduled visit, participants completed a questionnaire with the 19 selected items and answered questions about their asthma control status over the previous four weeks. After completing the questionnaire, pre-bronchodilator measurements of FEV1 were recorded. Asthma specialists interviewed the participants without knowledge of the participants' responses to the questionnaire. After the interview, asthma specialists rated the level of asthma control on a three-point scale of "poorly controlled", "less-controlled" and "well controlled"

This study was approved by each asthma specialist's university Institutional Review Board (R-0603-240-172 in Seoul National University Hospital).

A stepwise logistic regression method was used to identify items with the greatest validity in discriminating participants' status. The identifying items were done under the integrated rating system that combined specialist and guideline-based evaluation. To make an integrated rating, a dichotomous variable with a value of 0 (controlled) and 1 (uncontrolled) was used, where a specialist's rating of "poorly controlled"/"less controlled" was determined as "uncontrolled" and a specialist's rating of "well-controlled" was determined as "controlled". As in the global initiative for asthma (GINA) guideline's levels of asthma control (20), guideline ratings were considered "controlled" when six components of levels of asthma control were "controlled." If at least one component showed "partly controlled," the rating was considered "uncontrolled." Thus, integrated ratings of asthma control were scored as "controlled (level of 0)" when both the specialist's rating was "controlled" and the level of asthma control of all six components of the GINA guideline rating were "controlled."

All 19 items were entered as independent variables and the integrated rating was entered as a dependent variable. Items were entered into the model in a forward stepwise fashion. Items with a statistical significance level of P<0.05 were selected for inclusion in the final survey.

After the items to be included in the KACT were finalized, reliability was evaluated using the internal consistency reliability method and Cronbach's alpha. In scoring the items, higher scores indicated better asthma control. Two scoring options were used. In the first, the score was the sum of each item from a five-point scale with scores after summation ranging from four to 20. In the second, the score was the sum of dichotomous variables for each item, with 0 indicating "uncontrolled" and 1 indicating "controlled." These ranged from 0 for "uncontrolled" to 4 for "totally controlled."

Pearson correlation coefficients were computed between KACT scores, the integrated rating, and FEV1. ANOVA was used to evaluate the ability of KACT scores to discriminate between the groups based on two criteria. The first criterion was based on the integrated rating. Patients were divided into three groups according to asthma control based on the specialist's rating and the guideline rating. When there was a difference between the specialist's and guideline based ratings, the lower rating was used. The second criterion was based on percent predicted FEV1 value, with ≤60% for Group 1, >60%-<80% for Group 2, and ≥80%-100% for Group 3.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis was conducted to compare the two scoring options and the KACT evaluation in their ability to identify patients with asthma control problems. Odds ratio, sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive values, and the percent correctly classified were calculated at each scoring level or "cut-off point" for both KACT scoring options.

Of a total of 392 patients who completed the survey questionnaire, 305 answered all items with a possible guideline rating. The mean and SD of age of respondents was 56.1±18.5 yr. Of them 49.9% were males range 16-87. The duration of asthma treatment was 4.4±5.6 yr.

According to the specialist's ratings of asthma control, 56.3% of respondents were evaluated to have well-controlled asthma. According to the guideline ratings for asthma control, 48.6% had controlled levels of asthma control. Approximately 34.3% showed had well-controlled scores by the integrated rating that considered both the specialist's and guideline ratings. According to spirometry, 60% of the patients had showed a percent predicted FEV1 value of more than 80%.

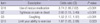

Four items were identified as significant by forward stepwise logistic regression analyses (Table 2). Use of rescue medication was selected as the most predictive item, followed by tightness or pain in chest, coughing, and limited ability to exercise.

The internal consistency of the four-item KACT survey was 0.60 for the total sample of 305 participants. The internal consistency of the 4-item KACT survey was 0.52 for the 198 participants categorized as uncontrolled according to the integrated rating.

The integrated rating showed the highest correlation with KACT scale scores (r=0.77, P<0.001). The correlation between KACT scores and specialist's ratings alone was also high (r=0.54, P<0.001), while the correlation between KACT scores and percent predicted FEV1 values was moderate (r=0.39, P<0.001).

The results of empirical validation test of KACT are presented in Table 3 in discriminating groups with different levels of asthma control. KACT scores for both of 2 scoring options showed significant difference in the level of asthma control between the integrated rating and the percent predicted FEV1 values.

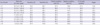

The ROC curve for the sum of total scores was 0.817 and for the sum of dichotomous variables was 0.799 (Figs. 1, 2). Table 4 presents the performance of the sum of total scores option for screening for control problems. Each score level represents a cut-off point that could discriminate controlled from uncontrolled patients. Sensitivity and specificity were 74.2% and 78.5%, respectively, at a cut-off point of 17. The overall agreement of KACT scale scores and integrated ratings ranged from 47.2% to 78.4%, with cut-off points of 11-19.

This is the first study to assess the feasibility of modifying the original ACT items to reflect local cultural background of patients. This modified ACT could provide primary care physicians with a useful tool for assessing the level of asthma control in Korean patients. In this study, the selected ACT items demonstrated reliability and discriminative properties in assessing asthma control, suggesting their applicability for use by Korean primary care physicians in actual clinical settings. According to the GINA guideline (20), assessment of asthma control and monitoring control is very important to maintain. Thus, given a recently published report that noted Korean PCPs use spirometry less than 10 times per month, even if they have a spirometry in their clinics (21), the KACT might be a useful tool for assessing asthma control in Korean primary care clinics.

Most of the ACT items developed by Nathan et al. (8) are available in Korean translations with commonly used terms. There was a report that Korean version of the ACT was a reliable tool for measuring asthma control and they studied correlation between Korean version of ACT and HRQL (17), but a patients' HRQL is not fully accounted for by one objective measure (18). So there may be a need to try to find out more accurate ACT items. Based on Korean cultural considerations and medical insurance policies, our working group decided to add or delete a few of the original ACT items. A total of 19 items were selected. The main differences between the original ACT and KACT regard items Q17 and Q18, concerning drug efficacy but the power of discrimination of asthma control status of items Q17 and Q18 were lower than usage of rescue medication. The selected four items have multidimensional constructs similar to the original ACT items, including patient symptoms (Q2: tightness or pain in chest, Q3: coughing), functional status (Q10: limits on your ability to exercise) and the use of rescue medication (Q16: use of rescue medication).

The KACT scores showed strong correlations with the specialist's rating (data not shown), pulmonary function test and the integrated rating. In Korea, guideline-based prescription of steroid inhalers is infrequent; patients' understanding of asthma management based on anti-inflammation medication is low; public campaigns about asthma are uncommon; and medical costs are relatively high. Therefore, asthma patients are likely not seeking help for mild asthma symptoms (19). Primary care physicians are likely to assess asthma control based only on clinical symptoms, without using objective assessment tools (22). Since many Korean asthma patients do not pay sufficient attenattention to their symptoms, they tend to overestimate their asthma control levels, resulting in undertreatment, similar to other Asian countries (23, 24). Primary care physicians must treat a relatively large number of patients in a limited time, so their assessment of asthma control is neither as reliable nor as accurate as it should be. Given these situations, the customized KACT, which reflects Korean conditions, might be able to help asthma control assessment in actual clinical practice. In many cases, asthma can be well-controlled and even completely controlled (25), so KACT might help asthma patients achieve better control by promoting communication between patients and primary care physicians in clinical settings.

In this study we used a guideline-based rating as well as specialist's ratings in assessing asthma control. Because of the lack of objective criteria for evaluating asthma symptoms, Korean asthma specialists tend to assess asthma control largely on the basis of clinical experience. Thus, it is reasonable to use both guideline-based ratings and an individual specialist's rating to assess asthma control. The specialist's ratings and guideline ratings identified well-controlled asthma in 56% and 48.6%, respectively, of study participants. However, only 34.3% were well considered controlled when both specialist's and guideline ratings were considered. Furthermore integrated rating showed the highest correlation with KACT scale scores (r=0.77) compared to specialist's ratings alone (r=0.54) and percent predicted FEV1 values (r=0.39), respectively. Using this integrated tool, we may be able to select more stringent KACT items.

This study has several limitations. The original ACT, without modification of the original items, has proven to be a useful tool for routine evaluation of asthma control by primary care physicians in Asian countries such as China (26) and Korea (17). But there is another report that a culturally targeted asthma intervention program in adult is effective in improving quality of life of asthma patients (27). Another limitation is that our modified KACT yields relatively lower reliability scores compared to the original ACT (0.83 in Nathan et al. compared to 0.52 in this study). To overcome these limitations, large prospective studies are needed to validate the KACT in clinical situations. Finally we did not control smoking status and some COPD patients who might be enrolled in our current research.

The main purpose of this study was to identify a suitable set of questionnaire items based on the original ACT items. We concluded that it was possible to formulate a valid, useful country-specific diagnostic tool for the assessment of asthma patients based on the original ACT that reflect sociocultural differences. We need further studies to validate these KACT items.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Area under the Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve for sum scoring option (range 4 to 20).

Table 1

Abbreviated text for 19 survey items used in the development

†Cut points for sum of counts scoring option determined based on face validity: Q4, Q6, Q13, Q16: count=1 for controlled response options 1, 2; count=0 for poorly controlled response options 3, 4, 5; Q19: count=1 for controlled response options 4, 5; count=0 for poorly controlled response options 1, 2, 3.

References

1. Wijnhoven HA, Kriegsman DM, Hesselink AE, Penninx BW, de Haan M. Determinants of different dimensions of disease severity in asthma and COPD pulmonary function and health-related quality of life. Chest. 2001. 119:1034–1042.

2. Shingo S, Zhang J, Reiss TF. Correlation of airway obstruction and patient-reported endpoints in clinical studies. Eur Respir J. 2001. 17:220–224.

3. Teeter JG, Bleecker ER. Relationship between airway obstruction and respiratory symptoms in adult asthmatics. Chest. 1998. 113:272–277.

4. Bates CA, Silkoff PE. Exhaled nitric oxide in asthma: from bench to bedside. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003. 111:256–262.

5. Rabe KF, Adachi M, Lai CK, Soriano JB, Vermeire PA, Weiss KB, Weiss ST. Worldwide severity and control of asthma in children and adults: the global asthma insights and reality surveys. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004. 114:40–47.

6. Lai CK, De Guia TS, Kim YY, Kuo SH, Mukhopadhyay A, Soriano JB, Trung PL, Zhong NS, Zainudin N, Zainudin BM. Asthma control in the Asia-Pacific region: the Asthma Insights and Reality in Asia-Pacific Study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003. 111:263–268.

7. Wolfenden LL, Diette GB, Krishnan JA, Skinner EA, Steinwachs DM, Wu AW. Lower physician estimate of underlying asthma severity leads to undertreatment. Arch Intern Med. 2003. 163:231–236.

8. Nathan RA, Sorkness CA, Kosinski M, Schatz M, Li JT, Marcus P, Murray JJ, Pendergraft TB. Development of the asthma control test: a survey for assessing asthma control. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004. 113:59–65.

9. Schatz M, Sorkness CA, Li JT, Marcus P, Murray JJ, Nathan RA, Kosinski M, Pendergraft TB, Jhingran P. Asthma Control Test: reliability, validity, and responsiveness in patients not previously followed by asthma specialists. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006. 117:549–556.

10. Variations in the prevalence of respiratory symptoms, self-reported asthma attacks, and use of asthma medication in the European Community Respiratory Health Survey (ECRHS). Eur Respir J. 1996. 9:687–695.

11. Netuveli G, Hurwitz B, Sheikh A. Lineages of language and the diagnosis of asthma. J R Soc Med. 2007. 100:19–24.

12. Michel G, Silverman M, Strippoli MP, Zwahlen M, Brooke AM, Grigg J, Kuehni CE. Parental understanding of wheeze and its impact on asthma prevalence estimates. Eur Respir J. 2006. 28:1124–1130.

13. Lee H, Arroyo A, Rosenfeld W. Parents' evaluations of wheezing in their children with asthma. Chest. 1996. 109:91–93.

14. Heck KE, Parker JD. Family structure, socioeconomic status, and access to health care for children. Health Serv Res. 2002. 37:173–186.

15. Wittich AR, Li Y, Gerald LB. Comparison of parent and student responses to asthma surveys: students grades 1-4 and their parents from an urban public school setting. J Sch Health. 2006. 76:236–240.

16. Cane RS, Ranganathan SC, McKenzie SA. What do parents of wheezy children understand by "wheeze"? Arch Dis Child. 2000. 82:327–332.

17. Kwon HS, Lee SH, Yang MS, Lee SM, Kim SH, Kim DI, Sohn SW, Park CH, Park HW, Kim SS, Cho SH, Min KU, Kim YY, Chang YS. Correlation between the Korean version of Asthma Control Test and health-related quality of life in adult asthmatics. J Korean Med Sci. 2008. 23:621–627.

18. Carranza Rosenzweig JR, Edwards L, Lincourt W, Dorinsky P, ZuWallack RL. The relationship between health-related quality of life, lung function and daily symptoms in patients with persistent asthma. Respir Med. 2004. 98:1157–1165.

19. Lee KJ, Kim KH, Kim HJ, Park IW, Shim JJ, Ahn CM, Uh ST, Oh YM, Yoo JH, Lee KH, Lee YC, In KH, Chang JH, Jeon YJ, Jung KS, Hwang YS. Attitudes and actions of asthma patients in Korea: asthma insight survey. Eur Respir J. 2008. ERS Congress Berlin Abstract E 3073.

20. Global strategy for asthma management and prevention. NHLBI/WHO Workshop Report. 2008 (update). Accessed on 6 February 2009. Available at: http://www.ginasthma.org.

21. Park MJ, Choi CW, Kim SJ, Kim YK, Lee SY, Kang KH, Shin KC, Lee JH, Kim YI, Lim SC, Park YB, Jung KS, Kim TH, Shin DH, Yoo JH. Survey of COPD management among the primary care physicians in Korea. Tuberc Respir Dis. 2008. 64:109–124.

22. Picken HA, Greenfield S, Teres D, Hirway PS, Landis JN. Effect of local standards on the implementation of national guidelines for asthma: primary care agreement with national asthma guidelines. J Gen Intern Med. 1998. 13:659–663.

23. Zhou X, Ding FM, Lin JT, Yin KS, Chen P, He QY, Shen HH, Wan HY, Liu CT, Li J, Wang CZ. Validity of asthma control test in Chinese patients. Chin Med J (Engl). 2007. 120:1037–1041.

24. Cho SH, Park HW, Rosenberg DM. The current status of asthma in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2006. 21:181–187.

25. Bateman ED, Boushey HA, Bousquet J, Busse WW, Clark TJ, Pauwels RA, Pedersen SE. GOAL Investigators Group. Can guideline defined asthma control be achieved? The Gaining Optimal Asthma Control Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004. 170:836–844.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download