Abstract

Functioning adrenocortical oncocytomas are extremely rare and most reported patients are 40-60 yr of age. To our knowledge, only 2 cases of functioning adrenocortical oncocytomas have been reported in childhood. We report a case of functioning adrenocortical oncocytoma in a 14-yr-old female child presenting with virilization. She presented with deepening of the voice and excessive hair growth, and elevation of plasma testosterone and dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate. She had an adrenalectomy. The completely resected tumor composed predominantly of oncocytes without atypical mitosis and necrosis. A discussion of this case and a review of the literature on this entity are presented.

An oncocytoma is a tumor that is composed predominantly of polygonal oncocytes with abundant granular and intensely eosinophilic cytoplasm. It occurs in virtually every organ, most commonly the kidney, salivary glands, and thyroid. An oncocytoma that arises in the adrenal gland is very rare and usually benign and nonfunctioning. Because of the unusual occurrence of functioning adrenocortical oncocytoma, particularly in childhood, we report here a case of adrenocortical oncocytoma in a girl presenting with virilization. We also discuss this case and review the literature in terms of pathologic classification and malignant potential.

A 14-yr-old girl presented with deepening of the voice and excessive hair growth as well as change in body habitus since about 1 yr prior to admission. She was born at full term without perinatal problems and had no special health problems previously. Her mother worried about not only her hypertrichosis but also her lack of menarche. Her body weight was 69.5 kg (95-97 percentile), height was 165.1 cm (90-95 percentile) and body mass index was 25.5 kg/m2. Her blood pressure was normal. Physical examination revealed acne on the face and a male pattern of excessive hair on the chin, anterior chest wall, lower abdomen and inner thigh (Fig. 1). A huge, hard mass was palpated on the right abdomen. Her breast was Tanner stage 2, but her bone age (17 yr) was advanced. She had mild clitomegaly. We performed a hormonal study for evaluation of virilization, which revealed increased plasma testosterone (>1,500 ng/dL, reference range: ≤32 ng/dL) and dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEA-S) (>1,000 µg/dL, reference range: ≤260 µg/dL) levels. Plasma 17-hydroxyprogesterone (17-OHP) was also increased (56.4 ng/mL, reference range: ≤2.3 ng/mL). Plasma adrenocorticotrophic hormone (ACTH) was 5.1 pg/mL (reference range: 5-37 pg/mL) and plasma cortisol was 26.7 µg/dL (reference range: 4-11 µg/dL). Plasma lutenizing hormone (LH) was 0.24 mIU/mL and plasma follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) was <0.1 mIU/mL. The abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed a 12×12×14 cm-sized, well-circumscribed, huge mass which displaced the right kidney anteromedially (Fig. 2). The positron emission tomography (PET) CT scan revealed a heterogeneous hypermetabolic mass only in the area between the liver and right kidney, which suggested a malignant retroperitoneal or adrenal tumor (Fig. 3). A whole body bone scan found no active lesions. We performed a low dose (0.5 mg q 6 hr for 48 hr) and high dose (2 mg q 6 hr for 48 hr) dexamethasone suppression test and the result of that was not compatible with Cushing's syndrome. She had a right adrenalectomy and her postoperative course was uneventful. The resected tumor was a huge encapsulated round mass, measuring 17.5×15×14 cm in dimension and 1,100 gm in weight. The outer surface was smooth and glistening (Fig. 4). Microscopically (Fig. 5), the tumor was composed of large cells with eosinophilic cytoplasm. Capsular or sinusoidal invasion was not noted and the subcapsular area showed a compressed normal adrenal cortex. Atypical mitosis and necrosis were absent. These findings were compatible with the diagnosis of oncocytoma. At 2 weeks after removal of the adrenal tumor, her serum testosterone and DHEA level decreased dramatically to normal ranges, respectively.

Virilization in an adolescent or woman can manifest as clitoral enlargement, increased muscle strength, acne, hirsutism, frontal hair thinning, deepening of the voice, and menstrual disruption due to anovulation. Some of the possible causes of virilization in women are polycystic ovary syndrome, androgen-producing tumors (of the ovaries, adrenal glands, pituitary gland), hypothyroidism, anabolic steroid exposure, congenital adrenal hyperplasia due to 21-hydroxylase deficiency (late-onset), and hormone replacement therapy (female-to-male) (1).

Adrenocortical neoplasms are rare in children and adolescents. Tumors account for less than 0.2% of all pediatric neoplasms and 1.3% of all carcinomas in patients less than 20-yr-old (2). Single tumors usually are benign unilateral adenomas and more rarely malignant carcinomas. Adrenocortical tumors can be either functional or non-functional. In children, most tumors are functional, with 80-90% having endocrine manifestations at diagnosis and up to 94% secreting excess hormones on further evaluation (3). Most children (50-84%) present with virilization (pubic hair, accelerated growth and skeletal maturation, an enlarged penis or clitoris, hirsutism and acne) due to excess androgen secretion.

The adrenocortical oncocytoma is extremely rarely found; only renal oncocytoma is commonly reported in children (4). Only a little more than 50 cases of adrenal oncocytoma have been reported in the literature (5). They were usually benign and nonfunctioning. The functioning adrenocortical oncocytomas have been reported so far in only 9 cases, of whom 7 patients were 40-60 yr of age and only 2 patients were 6 and 12 yr of age. The reported 2 children presented with virilization and pseudopuberty, and our patient also presented with virilization showing high serum testosterone and DHEA levels.

The major practical problem for our case was to differentiate benign from malignant adrenocortical oncocytoma after complete resection of the tumor. We considered her tumor as borderline because only one minor criterion was fulfilled according to the malignancy scoring system proposed by Bisceglia (6). As Juliano et al. reported a case of metastatic adrenocortical oncocytoma (7), we tried a metastatic work-up including a whole body bone scan, chest CT scan and PET-CT scan, which revealed negative findings. Based on the borderline criteria of pathologic classification and no metastatic evidence, we decided to just observe her without further post-operative chemoradiotherapy. However, she is being monitored by a physical examination and abdominal CT scan biannually for 2 yr, then annually for the next 5 yr.

In conclusion, we report a very rare case of virilizing adrenocortical oncocytoma, particularly in a female child. Although the malignant potential of this tumor is feeble and controversial, we must pay attention to recurrences because little is known of the tumor's long-term natural history.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 2

An abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan showed a 12×12×14 cm-sized, well-circumscribed, huge mass which displace the right kidney anteromedially.

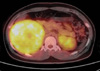

Fig. 3

The positron emission tomography (PET) CT scan revealed a heterogeneous hypermetabolic mass which suggested a malignant retroperitoneal or adrenal tumor.

Fig. 4

Gross findings of resected tumor. (A) Well-demarcated huge mass, (B) Cut surface of resected tumor showing smooth and glistening surface.

Fig. 5

Microscopic findings of resected tumor. (A) The tumor was composed of large cells with eosinophilic cytoplasm. The capsular or sinusoidal invasion was not noted and the subcapsular area showed a compressed normal adrenal cortex. (B) Atypical mitosis and necrosis were absent (H&E, A ×100, B ×400).

References

1. Yildiz BO. Diagnosis of hyperandrogenism: clinical criteria. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006. 20:167–176.

2. Chundler RM, Kay R. Adrenocortical carcinoma in children. Urol Clin North Am. 1989. 16:469–479.

3. Michalkiewicz E, Sandrini R, Figueiredo B, Miranda EC, Caran E, Oliveira-Filho AG, Marques R, Pianovski MA, Lacerda L, Cristofani LM, Jenkins J, Rodriguez-Galindo C, Ribeiro RC. Clinical and outcome characteristics of children with adrenocortical tumors: A report from the international pediatric adrenocortical tumor registry. J Clin Oncol. 2004. 22:838–845.

4. Chen TS, McNally M, Hulbert W, Di Sant'Agnese PA, Huang J. Renal oncocytosis presenting in childhood. Int J Surg Pathol. 2003. 11:325–329.

5. Tahar GT, Nejib KN, Sadok SS, Rachid LM. Adrenocortical oncocytoma: a case report and review of literature. J Pediatr Surg. 2008. 43:E1–E3.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download