Abstract

We performed a retrospective study to evaluate the feasibility and safety of extensive upper abdominal surgery (EUAS) in elderly (≥65 yr) patients with advanced ovarian cancer. Records of patients with advanced epithelial ovarian cancer who received surgery at our institution between January 2001 and June 2005 were reviewed. A total of 137 patients including 32 (20.9%) elderly patients were identified. Co-morbidities were present in 37.5% of the elderly patients. Optimal cytoreduction was feasible in 87.5% of the elderly while 95.2% of young patients were optimally debulked (P=0.237). Among 77 patients who received one or more EUAS procedures, 16 (20.8%) were elderly. Within the cohort, the complication profile was not significantly different between the young and the elderly, except for pleural effusion and pneumothorax (P=0.028). Elderly patients who received 2 or more EUAS procedures, when compared to those 1 or less EUAS procedure, had significantly longer operation times (P=0.009), greater blood loss (P=0.002) and more intraoperative transfusions (P=0.030). EUAS procedures are feasible in elderly patients with good general condition. However, cautious peri-operative care should be given to this group because of their vulnerability to pulmonary complications and multiple EUAS procedures.

Ovarian cancer is the leading cause of death among female reproductive tract cancers. Data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program database (1988-2001) shows that 45.6% of ovarian cancer are diagnosed among women older than 65 yr of age, and 76.9% of these elderly patients are diagnosed at an advanced stage of disease (1). Even within the same stages, young women survive longer than older women even after adjusting for life expectancy (2, 3). Several reports have suggested that the lower survival rate of elderly patients with ovarian cancer may be largely attributed to less aggressive treatment (4-9).

Maximal cytoreductive surgery is the most important procedure in the management of advanced ovarian cancer. However, it has been noted that elderly patients receive fewer operations and a lower percentage of optimal debulking (4, 10). Despite the common belief that elderly patients might not be able to tolerate the debilitating effects of radical surgery, recent developments in the field of peri-operative care, anesthesiology, and surgical techniques have significantly improved general safety and operability of radical surgery. Fortunately, a number of recent studies have reported that standard cytoreductive surgery is feasible and safe in elderly patients with advanced ovarian cancer (10-14). In these reports, optimal cytoreduction rates in elderly patients varied between 45% and 80% (10, 12-14).

Several studies have indicated that the application of more comprehensive surgical methods targeting upper abdominal disease can improve optimal cytoreduction rates and overall survival (15-21). The surgical approach incorporates the utilization of extensive upper abdominal surgery (EUAS), such as diaphragm stripping and/or resection, splenectomy, distal pancreatectomy, partial liver resection, resection of tumor from the porta hepatis, and cholecystectomy. However, in elderly patients, incorporation of EUAS into standard surgery raises a concern that elderly patients may not tolerate these radical and extensive procedures. Although few studies have addressed the feasibility of these procedures in elderly patients (12), there is scant data regarding the feasibility of EUAS in elderly patients with advanced ovarian cancer. The aim of this study was to review the experience of EUAS in elderly ovarian cancer patients and assess the feasibility and safety of these procedures.

With the approval of our Institutional Review Board (NCCNCS-09-303), we retrospectively identified patients who had undergone exploratory laparotomy for advanced epithelial ovarian cancer between January 2001 and June 2005 at the National Cancer Center of Korea. The following variables were recorded: age at diagnosis, histologic type, tumor grade, stage of the tumor, medical co-morbidities for Charlson index (22), preoperative CA125 value, presence of ascites, surgical procedures performed, size of residual disease, estimated blood loss, intraoperative complications, length of hospitalization, postoperative morbidity within 30 days of surgery, and survival outcome. Records from a center-based tumor registry were used to verify survival of the patients. Survival was calculated from the date of diagnosis until the last follow-up visit or death. Elderly patients were defined as women 65 yr of age or older.

All operations were performed by gynecologic oncologist-leading comprehensive surgery team including colorectal surgeons, urologic surgeons, thoracic surgeons and hepatobiliary surgeons (23). Standard cytoreductive procedures included hysterectomy, oophorectomy, low anterior resection, lymphadenectomy, and omentectomy. EUAS is defined as splenectomy, distal pancreatectomy, cholecystectomy, liver resection, diaphragm stripping and/or resection, and partial gastrectomy. Records of residual mass were retrieved for all patients and optimal cytoreduction was defined as a residual tumor size <1 cm in size. All patients were staged according to the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) staging system. All specimens were reviewed by gynecologic pathologists and graded according to the World Health Organization classification. Prophylaxis for thrombotic complications was given to all the patients who underwent surgery.

Data analyses were performed using STATA software (College Station, TX, USA). The median values between the two groups were compared using the Mann-Whitney U test. Frequency data were evaluated by the Fischer exact test or chi-square test, as appropriate. Survival rates were calculated using Kaplan-Meier methods, and differences were evaluated by the log-rank test and Cox hazard ratio analysis. All P values presented are two-sided, and associations are considered significant if the P value <0.05.

A total of 137 patients with advanced ovarian cancer including 32 elderly patients (≥65 yr of age) underwent primary cytoreductive surgery. The characteristics of the patients are described in Table 1. The median age of the elderly patients was 67 yr (range, 65-79 yr). Co-morbidities were present in 37.5% of the elderly patients. The number of co-morbidities was higher in the elderly without statistical significance (0.3 vs. 0.5, P=0.078). Charlson index (22) was higher in the elderly patients (0.188 vs. 0.167, P=0.049). The most common co-morbidity was cardiovascular disease. Four of 32 (12.5%) elderly patients had multiple co-morbidities. At the time of hospitalization, tumor stage, grade, and histology were not different between the two groups. Although the initial level of serum CA-125 was not different between the two groups, ascites was more frequently found in the elderly cohort without statistical significance (61.9% vs. 78.1%, P=0.091).

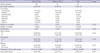

Standard surgery for ovarian cancer was performed on all patients enrolled in the present study. EUAS procedures were applied to all patients whenever it was necessary to debulk the tumor optimally. The list of EUAS procedures and the operative outcomes for each cohort are listed in Table 2. The most commonly performed EUAS procedure was splenectomy (43.8%). The second most common procedure was diaphragm stripping and/or resection (23.4%). Overall, 77 patients, including 16 elderly patients, received EUAS. The proportion of patients who received EUAS was not different between the two groups (58.1% vs. 50.0%, P=0.420). The proportion of patients who received multiple EUAS procedures was similar between the two groups (19.1% vs. 25.0%, P=0.465). The median estimated blood loss for the entire groups was 850 mL. The estimated blood loss and intraoperative transfusion rate were statistically similar between the two groups. The optimal debulking rate (residual mass <1 cm) was 95.2% for young patients and 87.5% for elderly patients (P=0.213).

Intraoperative injuries and post-operative morbidities within 30 days were described in Table 3. The most common intraoperative injury associated with EUAS was diaphragm perforation, resulting from aggressive diaphragmatic tumor debulking or diaphragmatic full thickness resection. The most common medical morbidity was infection. Pleural effusion and pneumothorax were the most common morbidities which possibly resulted from EUAS. We also observed that these complications are more frequent in elderly patients, but without statistical significance (6.7% vs. 18.8%, P=0.077). A total of 77 of 153 women received one or more EUAS procedures during their surgery. Among these patients, complications and morbidities were compared according to age (Table 4). Overall, the complications and morbidities were not significantly different. However, pleural effusion and pneumothorax were significantly more common in the elderly group (8.2% vs. 31.3%, P=0.028). Among the 5 elderly patients who received upper abdominal procedures and experienced postoperative pleural effusions or pneumothorax, five patients had resection and/or stripping of the diaphragm and three patients had splenectomy. None of the patients had malignant effusions before surgery. Among the five patients, one patient developed a pneumothorax during resection of the diaphragm; the patient recovered well with conservative care, including tube drainage. Four patients had postoperative pleural effusions which were successfully managed with tube drainage. In one of the four patients, pneumonia was developed. Despite intensive care, she died of infection after 51 postoperative days.

In 32 elderly patients with advanced ovarian cancer, we compared operative outcomes and complications according to the multiplicity of EUAS procedures (Table 5). The age, stage of the disease, number of co-morbidities, Charlson index, and initial CA-125 were similar between both groups. However, we observed that the elderly patients who received multiple (2 or more) upper abdominal surgical procedures had increased blood loss (800 vs. 1,600 mL, P=0.002), more frequent intraoperative transfusions (54.2% vs. 100%, P=0.030), and longer operating times (422.5 min vs. 609.5 min, P=0.002). Also, the elderly patients with multiple upper abdominal procedures had more frequent iatrogenic surgical morbidities (8.3% vs. 50.0%, P=0.023). Optimal debulking rates between the two groups were similar (91.7% vs. 75.0%, P=0.254).

The median duration of follow-up for the entire cohort was 38.2 months (range, 1.7 to 87.5). The progression free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) are illustrated in Fig. 1. The median PFS was 22 months (95% confidence interval [CI], 16.6-40.2) for the elderly patients, and 31.5 months (95% CI, 22.9-53.9) for the young patients (P=0.190, by log-rank test, Fig. 1A). Backward stepwise multivariate Cox hazard analysis revealed that the presence of gross residual tumor was the only independent risk factor predicting PFS (P=0.034, 95% CI, 1.05-3.22). In the elderly, the median OS was 57.8months (95% CI, 20.0-63.4), whereas the median OS was not reached in the young patients. The log rank test showed that elderly patients had a shorter OS than the younger group (P=0.016, Fig. 1B). Again, however, backward stepwise multivariate Cox proportional hazard analysis revealed that the presence of residual tumor was the independent prognostic factor (P=0.011, 95% CI, 1.32-8.72). In patients with age >75 yr, overall survival was less than 10 months in 4 of 5 patients in spite of optimal cytoreduction. The remaining one patient survived 57 months.

The present study showed that EUAS can be performed with careful perioperative management in elderly patients with advanced ovarian cancer. In the elderly patients, we achieved an optimal debulking rate of 87.5% with EUAS. We also observed that intraoperative complication rates, 30 day postoperative morbidity and other operative outcomes were similar between the young and elderly patients. For example, the frequency of infectious complications was not different between the young and elderly patients who had a splenectomy (12.5% vs. 8.3%, P=1.000). Therefore, we suggest that EUAS may be safe and feasible in fit, elderly patients.

In the recent study demonstrating that EUAS can help increase the optimal cytoreduction rate, Chi et al. (17) included patients up to 88 yr of age and reported a 76% of optimal cytoreduction rate. Recently, Wright et al. (10) reported the surgical outcome of 46 elderly women, including 33 cases with advanced disease. In the study, they reported that 2% of elderly patients had a splenectomy and the optimal cytoreduction rate for the elderly group (including 22% of early stage patients) was 81%. Recently, Sharma et al. (12) reported an 89.6% optimal debulking rate involving 77 elderly patients, including 26% early stage patients. They defined 'supraradical' surgical procedures as splenectomy, and/or diaphragm resection, and/or liver resection, and/or combined small and large bowel resection, and/or exenteration. In the study, 15 elderly patients (19.4%) underwent 'supraradical' procedures. In our study, we applied EUAS to 16 of 32 elderly patients (50.0%). Our optimal debulking rate (87.5%) was similar to the previous study. However, it should be noted we included only patients with advanced disease, while the previous studies included 22-26% patients of early stage ovarian cancers. As Bristow et al. (24) demonstrated in their meta-analysis, our data also showed that a high optimal debulking rate can be translated into an improved OS (median survival 57.8 months) in elderly patients with advanced ovarian cancer.

In terms of surgical complication, our data suggest that there is no difference between young patients and fit, elderly patients in general. This corresponds with the results of previous studies (10, 12, 13). However, our data raised a concern that the incorporation of upper abdominal procedures may increase the frequency of specific complications and may cause more physical burden to the elderly patients who underwent EUAS procedures. First, we observed that pleural effusions and pneumothorax were more likely to develop in elderly patients who underwent EUAS procedures. Post-operative pleural effusions are relatively common complications in patients who undergo diaphragm resection and/or stripping (25-27). Previous reports emphasize that most of the cases can be managed without respiratory compromise or further complications. Also, in the report by Eisenhauer et al. (26), the age of the patients who had effusions after diaphragm peritonectomy was not different from that of patients that did not undergo diaphragm peritonectomy. Therefore, at the present time, it is not clear that diaphragmatic surgery is the cause of more frequent post-operative pleural effusion in the elderly. However, given that elderly patients are more vulnerable to respiratory complications, such as pneumonia or respiratory distress, we recommend that intensive care should be given to the elderly patients, especially when they received diaphragm surgery and/or a splenectomy. Second, we found that elderly patients who received multiple EUAS had increased blood loss, longer operating time, and more frequent intraoperative transfusions. Since all of these factors can deteriorate the postoperative outcomes of elderly patients, unnecessary upper abdominal procedures should be minimized.

There were several limitations of our study. In addition to the small sample size of the study, one of the major limits of our study was the nature of the retrospective study design, which is vulnerable to selection bias. Therefore, the elderly patients in our study may not represent elderly patients from the general population. Second, our data did not provide an answer for a concern that EUAS may impair quality of life, especially in the elderly patient. Given that the profiles of complications and morbidities were similar between the young and elderly groups, it is very tempting to assume that the impairment of quality of life in elderly patients may not be more severe than young patients. However, a further prospective trial is necessary to elucidate this question. Third, physical age and mental status irrespective of chronological age used in this study must be considered in the future study. Finally, although we have recommended surgery to every elderly patient with a favorable performance score, no severe multiple co-morbidities and adequate activities of daily living, our study did not provide the exact selection criteria for recruiting the 'fit' elderly into surgery. Therefore, how to select 'fit' patients for extensive surgery, including upper abdominal procedures, is still not determined. Recently, Alphs et al. (11) suggested that age over 80 yr, poor nutritional state, and an unfavorable co-morbidity index can predict an unfavorable outcome in elderly patients. Janda et al. (28) also suggests that the risk factor profile, including age, stage, treatment facility, and co-morbidity, can help determine whether we should give standard surgery to elderly patients. Therefore, to improve the outcome of elderly ovarian cancer patients, it is necessary to launch a prospective randomize study to validate the usefulness of these predictive factors and to establish an adequate patient selection system.

Since recent evidences repeatedly stress that standard care should be given to elderly patients with advanced ovarian cancer, now the concern has shifted to how aggressive the surgery should be. Our results suggest that not only standard operative care but EUAS is feasible in fit elderly patients with advanced stage ovarian cancer. However, a gynecologist always should make every effort to minimize unnecessary radical procedures, especially in elderly patients. Also, more careful peri-operative care should be offered to elderly patients when they receive two or more EUAS procedures.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 1Kaplan-Meier survival analysis of the young and the elderly patients with advanced ovarian cancer. (A) Progression free survival distribution by age (P=0.190, by log-rank test). (B) Overall survival distribution by age (P=0.016, by log-rank test). |

Table 4

Comparison of complications between young and elderly patients who received upper abdominal surgical procedures

References

1. Choi M, Fuller CD, Thomas CR Jr, Wang SJ. Conditional survival in ovarian cancer: results from the SEER dataset 1988-2001. Gynecol Oncol. 2008. 109:203–209.

2. Yancik R, Ries LG, Yates JW. Ovarian cancer in the elderly: an analysis of Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program data. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1986. 154:639–647.

3. Chung HH, Hwang SY, Jung KW, Won YJ, Shin HR, Kim JW, Lee HP. Ovarian cancer incidence and survival in Korea: 1993-2002. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2007. 17:595–600.

4. Cloven NG, Manetta A, Berman ML, Kohler MF, DiSaia PJ. Management of ovarian cancer in patients older than 80 years of age. Gynecol Oncol. 1999. 73:137–139.

5. Bruchim I, Altaras M, Fishman A. Age contrasts in clinical characteristics and pattern of care in patients with epithelial ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2002. 86:274–278.

6. Edmonson JH, Su J, Krook JE. Treatment of ovarian cancer in elderly women. Mayo Clinic-North Central Cancer Treatment Group studies. Cancer. 1993. 71:615–617.

7. Gershenson DM, Mitchell MF, Atkinson N, Silva EG, Burke TW, Morris M, Kavanagh JJ, Warner D, Wharton JT. Age contrasts in patients with advanced epithelial ovarian cancer. The M.D. Anderson Cancer Center experience. Cancer. 1993. 71:638–643.

8. Markman M, Lewis JL Jr, Saigo P, Hakes T, Jones W, Rubin S, Reichman B, Barakat R, Curtin J, Almadrones L. Epithelial ovarian cancer in the elderly. The Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center experience. Cancer. 1993. 71:634–637.

10. Wright JD, Herzog TJ, Powell MA. Morbidity of cytoreductive surgery in the elderly. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004. 190:1398–1400.

11. Alphs HH, Zahurak ML, Bristow RE, Diaz-Montes TP. Predictors of surgical outcome and survival among elderly women diagnosed with ovarian and primary peritoneal cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2006. 103:1048–1053.

12. Sharma S, Driscoll D, Odunsi K, Venkatadri A, Lele S. Safety and efficacy of cytoreductive surgery for epithelial ovarian cancer in elderly and high-risk surgical patients. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005. 193:2077–2082.

13. Susini T, Amunni G, Busi E, Villanucci A, Carriero C, Taddei G, Marchionni M, Scarselli G. Ovarian cancer in the elderly: feasibility of surgery and chemotherapy in 89 geriatric patients. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2007. 17:581–588.

14. Uyar D, Frasure HE, Markman M, von Gruenigen VE. Treatment patterns by decade of life in elderly women (> or =70 years of age) with ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2005. 98:403–408.

15. Eisenkop SM, Friedman RL, Wang HJ. Complete cytoreductive surgery is feasible and maximizes survival in patients with advanced epithelial ovarian cancer: a prospective study. Gynecol Oncol. 1998. 69:103–108.

16. Eisenkop SM, Spirtos NM, Friedman RL, Lin WC, Pisani AL, Perticucci S. Relative influences of tumor volume before surgery and the cytoreductive outcome on survival for patients with advanced ovarian cancer: a prospective study. Gynecol Oncol. 2003. 90:390–396.

17. Chi DS, Franklin CC, Levine DA, Akselrod F, Sabbatini P, Jarnagin WR, DeMatteo R, Poynor EA, Abu-Rustum NR, Barakat RR. Improved optimal cytoreduction rates for stages IIIC and IV epithelial ovarian, fallopian tube, and primary peritoneal cancer: a change in surgical approach. Gynecol Oncol. 2004. 94:650–654.

18. Eisenhauer EL, Abu-Rustum NR, Sonoda Y, Levine DA, Poynor EA, Aghajanian C, Jarnagin WR, DeMatteo RP, D'Angelica MI, Barakat RR, Chi DS. The addition of extensive upper abdominal surgery to achieve optimal cytoreduction improves survival in patients with stages IIIC-IV epithelial ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2006. 103:1083–1090.

19. Zivanovic O, Eisenhauer EL, Zhou Q, Iasonos A, Sabbatini P, Sonoda Y, Abu-Rustum NR, Barakat RR, Chi DS. The impact of bulky upper abdominal disease cephalad to the greater omentum on surgical outcome for stage IIIC epithelial ovarian, fallopian tube, and primary peritoneal cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2008. 108:287–292.

20. Lee JH, Kim KS, Chung CW, Park YN, Kim BR. Hepatic resection of metastatic tumor from serous cystadenocarcinoma of the ovary. J Korean Med Sci. 2002. 17:415–418.

21. Bae J, Lim MC, Choi JH, Song YJ, Lee KS, Kang S, Seo SS, Park SY. Prognostic factors of secondary cytoreductive surgery for patients with recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer. J Gynecol Oncol. 2009. 20:101–106.

22. Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987. 40:373–383.

23. Lim MC, Kang S, Lee KS, Han SS, Park SJ, Seo SS, Park SY. The clinical significance of hepatic parenchymal metastasis in patients with primary epithelial ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2009. 112:28–34.

24. Bristow RE, Tomacruz RS, Armstrong DK, Trimble EL, Montz FJ. Survival effect of maximal cytoreductive surgery for advanced ovarian carcinoma during the platinum era: a meta-analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2002. 20:1248–1259.

25. Cliby W, Dowdy S, Feitoza SS, Gostout BS, Podratz KC. Diaphragm resection for ovarian cancer: technique and short-term complications. Gynecol Oncol. 2004. 94:655–660.

26. Eisenhauer EL, D'Angelica MI, Abu-Rustum NR, Sonoda Y, Jarnagin WR, Barakat RR, Chi DS. Incidence and management of pleural effusions after diaphragm peritonectomy or resection for advanced mullerian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2006. 103:871–877.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download