Abstract

A 70-yr-old man presented with painless gross hematuria. He underwent right nephrectomy for benign disease 9 yr ago. Computed tomography and cystoscopy showed a mass in the distal region of the right ureteral stump. He underwent right ureterectomy and bladder cuff resection. Pathological examination showed T1 and WHO grade 2 transitional cell carcinoma. At 6 months postoperatively, the patient is alive without any evidence of recurrence.

The occurrence of primary malignant tumor of the ureteral stump after nephrectomy for benign disease is extremely rare. With this reason, the remaining ureteral stump does not usually receive any additional attention after nephrectomy for non-functioning kidney. We report a case of a transitional cell carcinoma developed in a remnant ureter after retroperitoneoscopic simple nephrectomy for non-functioning kidney.

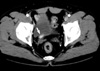

A 70-yr-old man presented with painless gross hematuria. He was an ex-smoker with 34 pack year and had a history of right retroperitoneoscopic simple nephrectomy for non-functioning kidney due to renal pelvic stone 9 yr ago. On physical examination, he had 4 scars less than 1 cm on his right flank. Urinalysis showed microscopic hematuria and other laboratory results were within normal range. Computed tomography revealed dilatation and wall-thickening in the proximal region and a solid mass in the distal region of the right ureteral stump (Fig. 1). Cystoscopy revealed a papillary mass protruding through right ureteral orifice (Fig. 2). Pathologic examination of the cold cup biopsy revealed WHO grade 2 transitional cell carcinoma of the ureter. Bone scan showed no evidence of distant metastasis. Patient underwent right ureterectomy with cuff excision of the bladder.

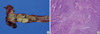

The gross specimen showed one papillary tumor just above the ureterovesical junction of the remnant ureter (Fig. 3A). The pathological examination of the specimen revealed WHO grade 2 transitional cell carcinoma of the ureter. The main tumor was infiltrated into the subepithelial connective tissue (T1). Urothelial dysplasia was detected in the distal resection margin of the specimen (Fig. 3B).

The postoperative course was uneventful. He was discharged on the 8th postoperative day. At 6 months postoperatively, the patient is alive without evidence of recurrence.

The occurrence of primary malignant tumor of the ureteral stump after nephrectomy for benign disease is extremely rare and present a significant diagnostic problem. These tumors may be defined as tumors occurring in the remnant ureter following nephrectomy or partial nephroureterectomy, in the absence of a tumor of the renal parenchyma, pelvis, or excised upper ureter (1). Malek et al. (2) reviewed the outcome of the ureteral stump in 4,883 nephrectomies performed for non-malignant disease for 29 yr and identified 4 cases of remnant ureteral stump tumor. Kim et al. (3) reported that the incidence of primary ureteral stump tumors was 2.51%, all of which occurred in patients with long standing renal diseases, such as pyonephrosis due to staghorn calculi or renal tuberculosis. However, these studies should be considered not as a true incidence but as a possibility of occurrence of primary ureteral stump tumors after simple nephrectomy. It is known that the peak incidence of upper tract transitional cell carcinoma is 10 per 100,000 per year, occurring in the age range of 75 to 79 yr and that age-adjusted annual incidence rates is about 0.7 per 100,000 person-years (4). Because renal pelvic tumors are generally not reported separately in U.S., worldwide statistics vary substantially between nations and are not accurate (4). Therefore further study will be needed to the accurate incidence of upper tract transitional cell carcinoma and primary tumors of the ureteral stump.

It is still an unveiled issue why malignant tumors occur in the closed ureteral stump. Several etiologic factors in the pathogenesis of genitourinary malignant tumors including chronic inflammation, leukoplakia, and exposure to carcinogenic substances, have been postulated (2). The presence of bladder, kidney, and ureter stones can cause irritation of the bladder epithelial wall, which was known as one of the possible causes of carcinogenesis. A 2-fold increase in bladder cancer risk was observed in patients with a history of bladder stones in the largest case-control study to date, regardless of history of UTI (5).

Though the association of squamous cell carcinoma or adenocarcinoma with stones has been well established, that of transitional cell carcinoma with stones has not been established so far. However, several studies have supported the evidence that transitional cell carcinoma is associated with urinary calculus. Kaufmann et al. (6) observed 6 cases of squamous cell carcinoma and 5 cases of transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder in 62 patients with spinal cord injury on long-standing catheters and suggested that bladder stone might be a significant risk factor for these cancers. In addition, in a prospective cohort study of patients diagnosed with kidney or ureteral stones, a standardized incidence ratio of 2.5 (95% confidence interval=1.8-3.3) was observed for renal pelvis/ureter cancer. The most common pathologic type of these tumors was the transitional cell carcinoma (71.7%), followed by squamous cell carcinoma (17.4%) (7). These findings suggest that the whole stone must be removed during the nephrectomy with the complete review of preoperative information. Once the fragmented stone is left, careful follow-up should be done.

In case of the diseased ureteral stump, its nature is not typical. Furthermore the ureteral stump is not visualized upon urography therefore the successful diagnosis may not be achieved easily. In this situation suspicion is important and other diagnostic tool such as computed tomography or retrograde ureterography can be helpful (8). In our case, an intravenous urography showed normal left calyces and ureter and did not show any evidence of abnormality in right residual urinary tract. Hematuria may have not been detected earlier if the mass was not protruding through right ureteral orifice. It says that the early symptom and the accurate diagnosis by proper diagnostic tool may prevent the invasive disease.

Figures and Tables

References

1. Wisheart JD. Primary tumour of the ureteric stump following nephrectomy. Presentation of a case and a review of the literature. Br J Urol. 1968. 40:344–349.

2. Malek RS, Moghaddam A, Furlow WL, Greene LF. Symptomatic ureteral stumps. J Urol. 1971. 106:521–528.

3. Kim YJ, Jeon SH, Huh JS, Chang SG. Long-term follow-up of ureteral stump tumors after nephrectomy for benign renal disease. Eur Urol. 2004. 46:748–752.

4. Flanigan RC. Wein AJ, Kavoussi LR, Novick AC, Partin AW, Peters CA, editors. Urothelial Tumors of the Upper Urinary Tract. Campbell-Walsh Urology. 2006. vol 2:9th ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders;1638.

5. Kantor AF, Hartge P, Hoover RN, Narayana AS, Sullivan JW, Fraumeni JF Jr. Urinary tract infection and risk of bladder cancer. Am J Epidemiol. 1984. 119:510–515.

6. Kaufmann JM, Fam B, Jacobs SC, Gabilondo F, Yalla S, Kane JP, Rossier AB. Bladder cancer and squamous metaplasia in spinal cord injury patients. J Urol. 1977. 118:967–971.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download