Abstract

Late complications of ureteral stents are frequent, and longer indwelling times are associated with an increased frequency of complications. Although there are reports of various complications of long-term indwelling ureteral stents, a renocolic fistula secondary to a perinephric abscess resulting from an indwelling ureteral stent has not been reported. Here, we present a fatal case of a renocolic fistula secondary to a perinephric abscess caused by an encrusted forgotten double J stent in a functionally solitary kidney.

Ureteral stent placement is an effective procedure to relieve ureteral obstruction. However, encrustation and bacterial colonization of stents are problematic and potentially lead to morbidity, such as infection, sepsis, or renal failure (1, 2). Morbidity associated with indwelling ureteral stents increases with indwelling time (3). In particular, the encrustation of forgotten ureteral stents can pose a serious challenge to the urologist, and complications related to this can be lethal (4).

A renocolic fistula is a very rare complication in the inflammation of the urinary tract, and the majority of reported cases are the result of xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis. A nephrectomy is usually required to manage a renocolic fistula associated with renal infection.

Recently, we had a 69-yr-old woman with a forgotten ureteral stent that caused pyelonephritis and a perinephric abscess, which then progressed and resulted in a connection with the ascending colon. To our knowledge, there has been no report of a perinephric abscess with a renocolic fistula caused by a forgotten double J stent. Here, we present a fatal case of renocolic fistula secondary to a perinephric abscess caused by an encrusted forgotten double J stent in a functionally solitary kidney.

A 69-yr-old woman presented to our emergency room with severe right flank pain that had developed one week earlier. She also complained of anuria for three days. She had a history of acute renal failure due to bilateral obstructive uropathy 22 months before this presentation; at that time, a double J stent had been inserted in her right urinary tract at another hospital. Since then, she had never seen a doctor for her urological problem, and the indwelling stent had been overlooked.

In the emergency room, her initial blood pressure was 160/100 mmHg and her body temperature was 36.0℃. A physical examination revealed right upper quadrant tenderness and right costovertebral angle tenderness. However, her lower abdomen was not distended, and urethral catheterization showed that the bladder was completely empty and had no residual urine. Initial blood tests showed leukocytosis (WBC count=14,900/µL) and an elevated creatinine level (6.6 mg/dL).

The abdominal plain radiography showed an indwelling double J stent on the right side. Renal ultrasonography revealed moderate hydronephrosis of the right kidney with an abscess-like collection in the upper pole of right kidney and right perinephric space (Fig. 1). Sonography also revealed severe hydronephrosis of the left kidney with cortical thinning that suggested a nonfunctional left kidney. To relieve the obstruction of a functionally single kidney, a right percutaneous nephrostomy catheter was placed on an emergency basis. Slightly brownish turbid urine was drained from the nephrostomy catheter. The urine and pus cultures yielded Pseudomonas aeruginosa.

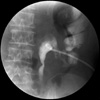

On the 7th day of hospitalization, the forgotten double J stent was removed intact via cystoscopy. The patient's serum creatinine level decreased to 1.7 mg/dL. On the 9th day of hospitalization, food eaten by the patient, including powdered red pepper and spinach, was unexpectedly detected in the drainage bag of the nephrostomy catheter. Abdominal dynamic computed tomography (CT) demonstrated the right renal pelvis was connected to the ascending colon via the perinephric abscess (Fig. 2). Antegrade pyelography also identified a fistula between the right pelvocalyceal system and ascending colon (Fig. 3). In addition, CT revealed that both ureters were obstructed at the level of an enhanced lesion of the uterus suggestive of a malignant lesion. The pathological findings of a biopsy specimen from the uterine cervix were consistent with squamous cell carcinoma.

While the patient was being managed conservatively, deferring the required surgical treatment, she suffered from acute heart failure. Her dyspnea worsened progressively, and the patient died on the 32nd day of hospitalization.

A forgotten ureteral stent may be associated with significant complications, including renal failure and sepsis. In this case, the forgotten ureteral stent was retained for 22 months and led to a renocolic fistula, a rare complication of severe renal infection.

In devising a treatment strategy for this patient, we faced a dilemma. The management of a renocolic fistula associated with renal infection usually requires a nephrectomy accompanied by repair of the fistula or resection of the involved segment of colon. Unfortunately, the patient possessed only a single functional kidney, and a right nephrectomy to treat the renocolic fistula might have left her dependent on dialysis. In addition, she had advanced cervical cancer that caused a bilateral ureteral obstruction, and this also needed to be considered. We considered performing an ileostomy to isolate the urinary tract from the intestine; however, surgical treatment was deferred because of her poor general condition. Finally, while being managed conservatively, she died of rapidly worsening acute heart failure, which may have been provoked by the stressful infection. Singh et al. reported that complications of forgotten indwelling ureteral stents can be lethal directly or indirectly (4).

It is unclear when the renocolic fistula occurred in our patient. No findings suggestive of renocolic fistula were observed during antegrade pyelography when the percutaneous nephrostomy catheter was initially placed. Because renocolic fistulas often lack colonic symptoms and appear normal in contrast studies, the fistula may have been present before her admission.

Because adequate drainage is short-lived in many cases, chronic stent placement must be used with caution, particularly when treating ureteral obstruction from extrinsic compression (5). Under these circumstances, periodic stent changes are mandatory, usually every three months. In our case, the patient had a single functional kidney and advanced cervical cancer as an extrinsic cause of ureteral obstruction; poor drainage via the forgotten stent resulted in a serious renal infection with anuria. To avoid the possible disastrous complications of indwelling ureteral stents, careful documentation and close follow-up of patients with ureteral stents is required. Lynch et al. (6) suggested the implementation of an electronic stent registry with automatic recall application for preventing forgotten ureteral stents. Of course, it cannot be overemphasized that increasing the patient's insight into his or her illness and explaining the possible complications of indwelling stents is a fundamental requirement before inserting ureteral stents.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Renal ultrasonography revealed moderate hydronephrosis of the right kidney with an abscess-like collection measuring 7.2×8.4 cm in the upper pole of the right kidney and right perinephric space. The proximal part of the forgotten ureteral stent was observed in the dilated renal pelvis.

Fig. 2

Computed tomography demonstrated that the right renal pelvis was connected to the ascending colon via the perinephric abscess. Contents with the same attenuation were observed in the ascending colon, right renal pelvis, and perinephric space. The nephrostomy catheter was placed in the right renal pelvis through the posterolateral aspect of the right kidney.

References

1. Richter S, Ringel A, Shalev M, Nissenkorn I. The indwelling ureteric stent: a 'friendly' procedure with unfriendly high morbidity. BJU Int. 2000. 85:408–411.

2. Paick SH, Park HK, Oh SJ, Kim HH, Kim SW. Characteristics of bacterial colonization and urinary tract infection after double-J ureteral stent indwelling. Korean J Urol. 2002. 43:291–295.

3. Damiano R, Oliva A, Esposito C, De Sio M, Autorino R, D'Armiento M. Early and late complications of double pigtail ureteral stent. Urol Int. 2002. 69:136–140.

4. Singh V, Srinivastava A, Kapoor R, Kumar A. Can the complicated forgotten indwelling ureteric stents be lethal? Int Urol Nephrol. 2005. 37:541–546.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download