Abstract

This study was designed to assess the effect of inflatable obstetric belts on uterine fundal pressure in the management of the second stage of labor. One hundred twenty-three nulliparas with a singleton cephalic pregnancy at term were randomized. Standard care was performed in the control group, and uterine fundal pressure by the Labor Assister™ (Baidy M-420/Curexo, Inc., Seoul, Korea) was utilized in addition to standard care in the active group. The Labor Assister™ is an inflatable obstetric belts that synchronized to apply uniform fundal pressure during a uterine contraction. The 62 women in the active group spent less time in the second stage of labor when compared to the 61 women in the control group (41.55±30.39 min vs. 62.11±35.99 min). There was no significant difference in perinatal outcomes between the two groups. In conclusion, the uterine fundal pressure exerted by the Labor Assister™ reduces the duration of the second stage of labor without attendant complications.

The most important force involved in the expulsion of a fetus is produced by maternal intra-abdominal pressure, and in most cases, bearing down is reflexive and spontaneous during the second stage of labor. Increased intra-abdominal pressure is generated by simultaneous muscle contraction and forced respiratory efforts with a closed glottis, which is commonly referred to as "pushing." This auxiliary force is required for the completion of labor (1). Uterine fundal pressure is described as an external force applied to the uppermost portion of the uterus in a caudal direction, typically with the intent of shortening the duration of the second stage of labor. Although uterine fundal pressure is commonly used in the management of a prolonged second stage of labor, particularly when maternal exhaustion or a non-reassuring fetal heart rhythm occurs during fetal head crowning, the role of uterine fundal pressure is understudied and remains controversial. Limited data exist on the safety and efficacy of fundal pressure (2); and there are no publications to date that report the use of fundal pressure in the second stage of labor because documentation of such a technique is often missing from medical records (3).

The aim of this study is to assess the effect of a Labor Assister™ (Baidy M-420/Curexo, Inc., Seoul, Korea) on uterine fundal pressure, which is an inflatable abdominal belt synchronized to apply uniform fundal pressure during spontaneous uterine contractions during the second stage of labor.

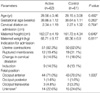

This randomized, controlled, and prospective study was conducted from November 2006 to August 2007. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the College of Medicine Pochon CHA University, and written informed consent was obtained from all patients. One hundred twenty-three pregnant women were recruited during the first stage of labor upon admission to the delivery unit. They were divided into two groups by randomly numbered envelopes upon full dilatation of the cervix; 62 were assigned to the active group and 61 to the control group (Table 1). The effects and safety of uniform fundal pressure and obstetric outcomes were then prospectively compared between the two groups.

All enrolled women were 20-35 yr of age, at term (37+0-41+6 weeks gestation), with a singleton cephalic presentation, a clinically adequate pelvis, and cervical dilatation <10 cm on admission. The estimated fetal body weight was >2.8 kg and <3.8 kg. Exclusion criteria included previous surgical history involving the uterine myometrium, a uterine anomaly, uterine myoma (>5 cm or multiple in number), history of gestational trophoblastic disease, known maternal medical diseases (hypertension, gestational diabetes mellitus, etc.), abnormal placental location, placental abruption, polyhydramnios, oligohydroamnios, suspected chorioamnionitis, abnormalities of the abdominal wall (hematoma or erythema), abnormal fetal heart monitoring at the time of enrollment, abnormal uterine activity, current history of drug or alcohol abuse, meconium-stained amniotic fluid, and intrauterine fetal growth restriction. A power analysis was performed to determine the appropriate sample size in relation to the difference of the duration of second stage. The computation was based on α level of 0.05% and 80% power. Assumed the difference of second stage of labor for calculation was 15 min and standard deviation was 30 min based upon previous study (4). A sample size of 50 in each group was planned, initial enrollment of 127 women, and 124 women completed the study protocol.

The Labor Assister™ consists of a tocotransducer, a control unit, and an inflatable belt (Fig. 1). The tocotransducer on the inflatable belt detects uterine contractions and sends the signal to the control unit, which then injects 200 mmHg of air into the belt for 30 sec. The frequency of inflation was limited to fewer than 7 times per 15 min. All patients wore the belt in the first stage of labor, but were unable to see the belt due to a draped screen. In addition, all the women, whether randomized to the belt or the control group, received standard management of the second stage of labor, which includes one-to-one support, continuous electronic fetal heart rate monitoring, and care from midwife. Augmentation of labor by an intravenous infusion of oxytocin and analgesia by an intramuscular injection of nalbupine or an epidural anesthesia were available at the discretion of the obstetrician. Operative deliveries were performed if clinically indicated. Upon full dilation of the cervix, indicating the onset of the second stage of labor, the Labor Assister™ was switched on in the active group. As a uterine contraction started, the inflatable obstetric belt was inflated synchronously and maintained at 200 mmHg for 30 sec. The Labor Assister™ was not used for more than 3 hr and was discontinued when delivery was imminent, when the obstetrician decided to remove the device, or when the patient requested removal of the device. All of the participants had continuous external fetal heart monitoring.

After delivery, all participants were followed up by questionnaire to grade their level of satisfaction. Active versus control group differences were analyzed for statistical significance by using Student's t test, chi-square test, and Fisher's exact test. Contributing factors for the duration of the second stage of labor were analyzed with multiple regression analysis and stepwise-selection method.

The patients' clinical characteristics are listed in Table 1. There were no significant differences between the active and control groups in terms of maternal age, gestational age, cervical dilation on admission, maternal height, and weight. Labor at term was the most common indication for admission in both groups. Rupture of membranes was less frequent in the active group (19.35%) compared with the control group (31.14%). The most common fetal position was occiput anterior in both groups.

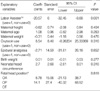

There was a significant decrease in duration of the second stage of labor in the active group as compared with the control group (41.55 min compared with 62.11 min, P=0.001). There was also a lower incidence of operative vaginal deliveries, perineal lacerations, and use of oxytocin in the active group, although these observations were not statistically significant. There were no considerable differences in birth weight, neonatal head circumference, Apgar scores, number of neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) admissions, meconium-stained amniotic fluid, epidural anesthesias, or length of stay for either the mother or neonate (Table 2).

Based on multiple regression analysis, the independent variables related to the duration of the second stage of labor was determined. A positive relationship existed with maternal age, use of oxytocin, birth weight, neonatal head circumference, and fetal head position; however, these were not statistically significant. A negative relationship was not significant between the duration of the second stage of labor and maternal height, maternal weight, or administration of epidural analgesia, with the exception of use of the Labor Assister™ (coefficient, -20.57; standard error, 6; P=0.001; Table 3). Thus, fundal pressure exerted by the Labor Assister™ was the most powerful contributor for shortening the duration of the second stage of labor.

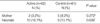

Two cases of maternal complications and 10 cases of neonatal complications were found in the active group, and 5 cases of maternal complications and 8 cases of neonatal complications were found in the control group (Table 4). Regarding the maternal complications, one patient with dysuria and one vaginal laceration were noted in the active group, and a perineal laceration, a vaginal hematoma, two vaginal lacerations, and one vulvar hematoma were noted in the control group. The following neonatal complications were recorded in the active group: persistent fetal circulation (n=1), talipes (n=1), sepsis (n=1), feeding disorder (n=3), small for gestational age (n=1), neonatal aspiration (n=2), and transient tachypnea of the newborn (n=3). Complications noted in the control group included sepsis (n=2), cephalhematoma (n=1), intercostal retractions (n=1), neonatal asphyxia (n=1), neonatal aspiration (n=2), and transient tachypnea of the newborn (n=3). There were no serious complications reported, and none were thought to be associated with the use of the Labor Assister™. Based on a postpartum questionnaire, more women reported positively about the device in the active group in terms of confidence, comfort, and satisfaction.

This randomized controlled trial with the Labor Assister™, which was developed to detect uterine contractions and apply synchronous uniform fundal pressure, demonstrates a significant reduction in duration of the second stage of labor. There were no considerable differences in perinatal outcomes or complications between groups attributed to the use of the Labor Assister™.

There are few studies about the safety and efficacy of fundal pressure (2). In 1991, Zhao (4) demonstrated that the use of this mechanical device during the second stage of labor shortened its duration (40 min 23 sec vs. 59 min 59 sec) and reduced the incidence of instrument deliveries. However, Cox et al. (5) reported that this inflatable obstetric belt did not reduce the duration of the second stage of labor or operative delivery rates in nulliparas with epidural anesthesia in 1999. In 2002, Buhimschi et al. (6) demonstrated that contraction-enhancing maneuvers with semi-inflated disposable cuffs during the second stage of labor increased intrauterine pressure by 86% with Valsalva and fundal pressure and by 28% with fundal pressure during spontaneous uterine contractions. In this study, more than half of the maximal force originates from the uterine contraction, 30% from Valsalva and 17% from fundal pressure. In our previous study (7), we observed continuous intrauterine pressure was maintained by the Labor Assister™ during uterine contractions, although manual fundal pressure and maternal Valsalva pushing produced higher intrauterine pressure with irregular intensity (72 mmHg with Labor Assister™ vs. 112 mmHg with manual fundal pressure and 129 mmHg with maternal Valsalva pushing). This study demonstrated that the use of this device is safe.

In recent years, there has been a significant increase in the use of epidural anesthesia during labor as a method of pain relief. Epidural anesthesia may induce some disadvantages, such as prolongation of the first and second stages of labor (8) and an increased amount of oxytocin (9). In addition, it is associated with an increased chance for malrotation of the fetal head and instrument deliveries (10). Physiologic mechanisms utilized by epidural anestheia to affect the normal course of labor include a reduction in endogenous oxytocin release (attenuation of Ferguson's reflex) (11) or a decrease in uterine myometrial contractility via sympathetic neural blockade (9). These hypotheses are supported by evidence that intrauterine pressure in the second stage of labor is decreased with an epidural anesthesia (12). Various trials have been performed in an attempt to minimize these disadvantages, but none have been successful. Decreased intrauterine pressure, which is one of the main disadvantages of epidural anesthesia, would be expected to be neutralized by means other than increasing intrauterine pressure; and fundal pressure could be an alternative method. In previous studies, uterine fundal pressure during the second stage of labor was found to increase complications such as shoulder dystocia (13), perineal lacerations (14), uterine rupture (15), and uterine inversion (16). Excessive fundal pressure can increase fetal intracranial pressure, resulting in a significant decrease in cerebral blood flow and non-reassuring fetal heart rate patterns. Cord compression and functional alterations in the intervillous spaces caused by the mechanical forces of fundal pressure compromise fetal status, leading to fetal hypoxemia and asphyxia (17). In addition, legal and professional practice guidelines concerning the use of fundal pressure in the normal second stage of labor do not currently exist.

The Labor Assister™ provides uniform fundal pressure during spontaneous uterine contractions in the second stage of labor, which could help maternal pushing, prevent maternal fatigue and exhaustion, and shorten the duration of the second stage of labor. In this study, complications associated with the device were not noted. The application of fundal pressure in the second stage could be uncomfortable due to the pain of uterine contractions; however, according to the results of the questionnaire, none of the patients complained about the device, and a greater number of patients responded positively with respect to confidence, comfort, and satisfaction. In the future, a larger scale study will be needed to determine the clinical usefulness of the Labor Assister™.

In conclusion, the Labor Assister™ is relatively safe and helpful in both reducing duration of the second stage of labor and preventing prolongation.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Labor Assister™ (Baidy M-420/Curexo, Inc. Seoul, Korea). ①controller ②belt ③tocotransducer ④air hose

References

1. Cunningham FG, Leveno KJ, Bloom SL, Gilstrap LC, Wenstrom KD. Parturition. Williams obstetrics. 2005. 22th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill;151–186.

2. Merhi ZO, Awonuga AO. The role of uterine fundal pressure in the management of the second stage of labor: a reappraisal. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2005. 60:599–603.

3. Kline-Kaye V, Miller-Slade D. The use of fundal pressure during the second stage of labour. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 1990. 19:511–517.

4. Zhao SF. Evaluation of an insufflatabe abdominal girdle in shorting the second stage of labor. Zhonghua Fu Chan Ke Za Zhi. 1991. 26:262–265. 321

5. Cox J, Cotzias CS, Siakpere O, Osuagwu FI, Holmes EP, Paterson-Brown S. Does an inflatable obstetric belt facilitate spontaneous vaginal delivery in nulliparae with epidural analgesia? Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1991. 106:1280–1286.

6. Buhimschi CS, Buhimschi IA, Malinow AM, Kopelman JN, Weiner CP. The effect of fundal pressure manoeuvre on intrauterine pressure in the second stage of labour. BJOG. 2002. 109:520–526.

7. Park Y, Roycroft PR, Song CH, Hahn S. The labor assister system™, automated system to facilitate normal vaginal delivery. Int J Assistive Robotics Mechatronics. 2006. 7:9–14.

8. Thorp JA, Hu DH, Albin RM, McNitt J, Meyer BA, Cohen GR, Yeast JD. The effect of intrapartum epidural analgesia on nulliparous labour: a randomized, controlled, prospective trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1993. 169:851–858.

9. Newton ER, Schroeder BC, Knape KG, Bennet BL. Epidural analgesia and uterine function. Obstet Gynecol. 1995. 85:749–755.

10. Howell CJ. Epidural versus non-epidural analgesia for pain relief in labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000. 2:CD000331.

11. Goodfellow CF, Hull M, Swaab D, Dogterom J, Buijs RM. Oxytocin deficiency at delivery with epidural analgesia. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1983. 90:214–219.

12. Bates R, Helm C, Duncan A, Edmonds DK. Uterine activity in the second stage of labour and the effect of epidural analgesia. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1985. 92:1246–1250.

13. Bahar AM. Risk factors and fetal outcomes in cases of shoulder dystocia compared with normal deliveries of a similar birthweight. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1996. 103:868–872.

14. Cosner KR. Use of fundal pressure during second-stage labour. A pilot study. J Nurse Midwifery. 1996. 41:334–337.

15. Pan HS, Huang LW, Hwang JL, Lee CY, Tsai YL, Cheng WC. Uterine rupture in an unscarred uterus after application of fundal pressure. A case report. J Reprod Med. 2002. 47:1044–1046.

16. Lee WK, Baggish MS, Lashgari M. Acute inversion of the uterus. Obstet Gynecol. 1978. 51:144–147.

17. Amiel-Tison C, Sureau C, Shnider SM. Cerebral handicap in full-term neonates related to the mechanical forces of labour. Baillieres Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 1988. 2:145–165.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download