Abstract

Arterial stiffness is an important contributor to the development of cardiovascular disease. We investigated the effect of short duration exercise using the treadmill test on arterial stiffness in the presence of coronary artery disease. We enrolled patients with and without coronary artery diseases (CAD and control group, 50 patients each) referred for treadmill testing. Brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity (baPWV) were measured before and after treadmill testing. Values of baPWV were significantly reduced at 10 min after exercise in both groups, more in the CAD group than in the control group (baseline baPWV and post-exercise change [cm/sec]: 1,527±245 and -132±155 in the CAD group, 1,439±202 and -77±93 in the control group, respectively, P for change in each group <0.001, P for difference in changes between the two groups <0.001). These findings persisted after adjusting for age, body mass index, systolic blood pressure, mean arterial pressure (MAP), MAP decreases, and baseline baPWV. Significant post-exercise baPWV reductions were observed in both groups, and more prominently in the CAD group. This finding suggests that short-duration exercise may effectively improve arterial stiffness even in patients with stable coronary artery disease.

Large elastic arteries in the central region and medium-sized muscular arteries have two functions, i.e., they act as low resistance conduits and as flow pulsation buffers (1). Moreover, a reduction in buffering capacity may increase systolic blood pressure (BP), left ventricular afterload, and pulsatile flow in capillary beds and reduce the diastolic contribution to blood flow in the coronary artery (2). Arterial stiffness is determined by the properties of the arterial wall matrix and by vascular smooth muscle tone, and may be changed immediately by an alteration in vascular smooth muscle tone caused by exercise (3). Exercise training-induced alterations in arterial stiffness would be of great benefit to those with coronary artery disease (CAD), and would potentially reduce myocardial oxygen demand and ischemic symptoms (4).

In the present study, we investigated the effect of short-duration exercise on arterial stiffness in patients with coronary artery disease, by repeatedly measuring brachial-ankle (ba) pulse wave velocity (PWV); an established non-invasive means of assessing arterial stiffness.

Fifty patients that underwent percutaneous coronary intervention (CAD group) and 50 patients without a history of cardiovascular disease (control group) who were referred for treadmill testing by physicians mostly due to atypical chest pain, were prospectively enrolled. Patients who were positive for myocardial ischemia on treadmill tests or those with comorbid conditions that limited exercise were excluded to ensure adequate exercise duration. Thus, patients with residual ischemia after PCI was excluded from CAD group and patients with overt clinical coronary artery disease was excluded from control group.

Brachial-ankle PWV was measured using an automatic PWV measurement system (Form-PWV/ABI, Colin, Komaki, Japan) in both brachia and ankles before treadmill exercise testing. This instrument simultaneously records baPWV, and brachial and ankle blood pressures on left and right sides, and provides an electrocardiogram and heart sounds. After baseline measurements, each subject performed symptom limited treadmill exercise testing according to the Bruce protocol. At 10 min after the completion of exercise, baPWV was remeasured. Heart rate and blood pressure (BP) were continuously monitored during exercise. For the analysis, baPWV values measured in both arms were averaged.

All values are expressed as means±standard deviation (SD). Statistical analysis was performed using SAS (SAS System for Windows 9.00, Cary, NC, U.S.A.). The chi-square test and the unpaired t-test were used to assess differences between the two groups at baseline. Linear correlations between parameters were established by Pearson correlation analysis. The paired t-test was used to compare pre- and post-exercise results, and the independent t-test was used to compare the effect of exercise in both groups. Multiple linear regression analysis was used to evaluate associations between baPWV changes and independent variables, and stepwise regression was used to select independent variables. P values of less than 0.05 were considered significant.

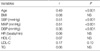

The clinical characteristics and laboratory findings of the study subjects are shown in Table 1. Mean age was higher in the CAD group, and the CAD group contained more male patients and hypertensive patients than the control group. The CAD group had a lower mean left ventricular ejection fraction, a lower mean LDL cholesterol, a higher baPWV, and a shorter treadmill exercise duration than the control group. The patients with CAD took more medicines, such as aspirin, β-blockers, renin-angiotensin system inhibitors, and HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors. Baseline baPWV values were found to correlate significantly with age, systolic BP (SBP), mean arterial pressure (MAP), and diastolic BP (DBP) (Table 2).

Brachial-ankle PWV values were significantly lower at 10 min after exercise than at baseline in both groups. However, this decrease was significantly larger in the CAD group, thus baPWV in the CAD group was initially higher than in the control group but became similar after exercise. In the control group, SBP and MAP were significantly lower at 10 min after exercise than at baseline, but DBP was not. In the CAD group, MAP was significantly lower at 10 min after exercise than at baseline (Table 3), whereas SBP was marginally lower, and DBP was not significantly different. Heart rates were higher at 10 min after exercise than at baseline in both groups (Table 3). By multivariate analysis, the CAD group showed a larger decrease in baPWV after exercise than the control group after adjusting for age, BMI, SBP, MAP, MAP reduction, and baseline baPWV (Table 4).

Arterial stiffness increases left ventricular afterload and alters coronary perfusion (5), and has been independently associated with target organ damage and increased cardiovascular morbidity and mortality (6). Brachial-ankle PWV is a simple marker of arterial stiffness (7, 8) and mainly reflects large artery stiffness, although it has also been reported to reflect endothelium-dependent peripheral vasodilation.

Changes in vascular wall distensibility may be induced by changes in the quality and quantity of vascular fibrous matrix (e.g., elastic fibers and collagen fibers in media: an organic factor) and by changes in smooth muscle tone (a functional factor). Elastic fiber is the primary determinant of vascular distensibility under physiologic conditions (9, 10). Moreover, the elastin-collagen compositions of arterial walls represent a more chronic component of arterial stiffness and changes only over years, thus it is unlikely that short-duration aerobic exercise changes these structural components (11). Instead, arterial compliance is probably altered in the short terms, or even acutely, via the modulation of the sympathetic-adrenergic tone of smooth muscle cells in arterial walls (12), which is affected by autonomic nervous activity and vasoactive agents derived from vascular endothelial cells, e.g., nitric oxide (NO), prostacyclin, and endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor (13). In particular, the production of NO is important, because it is a potent endothelium-dependent vasodilator and reduces vasoconstrictor response to α-adrenergic receptor stimulation (14). Moreover, pulsatile flow in the aorta associated with exercise training might evoke the acute release of NO, upregulate NO production, and increase the productions of other vasodilatory factors (15-17). In CAD patients, endothelial dysfunction develops secondary to reduced NO production and early reactivation by reactive oxygen species (18). In the present study, baPWV, which was higher in the CAD group at baseline, was found to be reduced significantly at 10 min after exercise in both groups, and because this decrease was larger in the CAD group, no difference in baPWV was observed between the two groups after exercise. These observations suggest that short-duration exercise affects arterial stiffness even in patients with CAD. We speculate that the mechanism involved may be related to the restoration of an equilibrium between NO production and inactivation by reactive oxygen species, which also appears to be the primary mechanism underlying exercise training-mediated perfusion improvements in CAD patients (18).

BP and age have been reported to be important determinants of baPWV in healthy individuals (7, 19), which is consistent with the findings of the present study. Exercise duration is significantly different between the two groups which might be a confounding factor. However, exercise duration is longer and the proportional change of baPWV is smaller in control group, and moreover exercise duration is not correlated to both absolute and relative change of baPWV (data not shown). Thus it is not probable that different exercise duration is a significant confounding factor.

Because, as mentioned above, CAD group members were taking more medications, it is unclear whether our findings suggest that patients with stable CAD have the potential to reverse arterial stiffness with exercise despite the presence of disease or whether they reflect an effect of the medications taken, such as aspirin, β-blocker, renin-angiotensin system inhibitor, and HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor. The lower level of LDL-cholesterol in the CAD group was probably due to HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors.

However, considering the higher baseline baPWV value in the CAD group, it appears that medications do not completely normalize arterial stiffness in CAD patients and that short-duration exercise seems to independently improve arterial stiffness immediately. Because majority of patients in CAD group and only a small number of persons in control group was taking one or more of the drugs which influence endothelial functions, statistical adjustment is not feasible with our data. Complete exclusion of the effects of medication probably can only be performed by experimental design in which normal control group is given the same medications.

Still, it is rather puzzling that CAD patients showed more prominent reduction in baPWV than control group and resulted in similar level of baPWV after exercise. This apparent 'reversibility' of arterial stiffness might be related to the duration and extent of atherosclerosis. As discussed above, arterial stiffness can be accounted by both reversible and irreversible component. We speculate that those in relatively early course of CAD may have more reversible component related to endothelial dysfunction and less irreversible component such as structural change of vascular wall. This group of patients has higher baseline baPWV due to the endothelial dysfunction but much of this functional abnormality might be reversible by some intervention, such as short-duration exercise in this study. Patients in the CAD group had undergone percutaneous coronary intervention and those with findings of residual ischemia were excluded by exercise test. This exclusion may have resulted in selection of patients with lower risk and less extensive coronary artery disease.

However, as a limitation of this study, we do not have enough information on the duration and extent of CAD in the patient group. Also, it is not possible to investigate this speculation further by measuring biomarkers of NO production and oxidative stress. Another potential limitation is that only brachialankle PWV was measured in our study. If markers of central blood pressure (20, 21) had been measured, different findings might have been found. In previous studies, aerobic exercise improved peripheral arterial stiffness but not central arterial stiffness (22), and central arterial stiffness was a better prognostic factor than peripheral arterial stiffness (23). However, this does not mean that peripheral arterial stiffness is meaningless, which has been shown to have prognostic value in another study (24), and also shown to be correlated to central arterial stiffness (8). It is likely that central arterial stiffness is a better index but peripheral arterial stiffness measured by baPWV is a very convenient alternative. These points should be subjects of future studies.

Another weakness of the study is that we do not have data on the heart rate and blood pressure at the time of PWV measurement. Because these variables acutely influence baPWV, this can be a potential source of confounding. However, we assume that heart rate and blood pressure was probably not different from the baseline at 10 min post-exercise.

Though our study showed immediate short-term response to exercise, evidence is scarce on whether repeated short-duration exercise may result in a persistent and long-term improvement of arterial stiffness. Further study is needed on this question, considering that frequent short-bout exercise is being discussed as a practical alternative to conventional long-duration exercise (25, 26).

In conclusion, in the present study, we prospectively investigated the effects of short-duration exercise on arterial stiffness by measuring baPWV in patients with or without CAD. A significant reduction in baPWV was observed at 10 min after short-term aerobic exercise in both groups, and in the CAD group this decrease was more prominent. These observations suggest that short-duration exercise training may be effective at improving arterial stiffness even in patients with coronary artery disease, at least in short-term. Clinical study is needed to see whether repeated short-duration exercise will improve arterial stiffness in CAD patients in long-term.

Figures and Tables

Table 2

Correlations between baPWV and clinical parameters at baseline

The values shown are Pearson correlation coefficients.

BMI, body mass index; SBP, systolic blood pressure; MAP, mean arterial pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; HR, heart rate; HDL-C, high density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C, low density lipoprotein cholesterol, TG, triglyceride; baPWV, brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity.

References

1. Sugawara J, Otsuki T, Tanabe T, Maeda S, Kuno S, Ajisaka R, Matsuda M. The effects of low-intensity single-leg exercise on regional arterial stiffness. Jpn J Physiol. 2003. 53:239–241.

2. Arnett DK, Evans GW, Riley WA. Arterial stiffness: a new cardiovascular risk factor? Am J Epidemiol. 1994. 140:669–682.

3. Sugawara J, Maeda S, Otsuki T, Tanabe T, Ajisaka R, Matsuda M. Effects of nitric oxide synthase inhibitor on decrease in peripheral arterial stiffness with acute low-intensity aerobic exercise. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004. 287:H2666–H2669.

4. Edwards DG, Schofield RS, Magyari PM, Nichols WW, Braith RW. Effect of exercise training on central aortic pressure wave reflection in coronary artery disease. Am J Hypertens. 2004. 17:540–543.

5. Wada T, Kodaira K, Fujishiro K, Maie K, Tsukiyama E, Fukumoto T, Uchida T, Yamazaki S. Correlation of ultrasound-measured common carotid artery stiffness with pathological findings. Arterioscler Thromb. 1994. 14:479–482.

6. Schiffrin EL. Vascular stiffening and arterial compliance. Implications for systolic blood pressure. Am J Hypertens. 2004. 17:39S–48S.

7. Asmar R, Benetos A, London G, Hugue C, Weiss Y, Topouchian J, Laloux B, Safar M. Aortic distensibility in normotensive, untreated and treated hypertensive patients. Blood Press. 1995. 4:48–54.

8. Yamashina A, Tomiyama H, Takeda K, Tsuda H, Arai T, Hirose K, Koji Y, Hori S, Yamamoto Y. Validity, reproducibility, and clinical significance of noninvasive brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity measurement. Hypertens Res. 2002. 25:359–364.

9. Berry CL, Greenwald SE, Rivett JF. Static mechanical properties of the developing and mature rat aorta. Cardiovasc Res. 1975. 9:669–678.

10. Kakiyama T, Sugawara J, Murakami H, Maeda S, Kuno S, Matsuda M. Effects of short-term endurance training on aortic distensibility in young males. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2005. 37:267–271.

11. Safar ME, Laurent S, Pannier BM, London GM. Structural and functional modifications of peripheral large arteries in hypertensive patients. J Clin Hypertens. 1987. 3:360–367.

12. Boutouyrie P, Lacolley P, Girerd X, Beck L, Safar M, Laurent S. Sympathetic activation decreases medium-sized arterial compliance in humans. Am J Physiol. 1994. 267:H1368–H1376.

13. Ekblom B, Kilbom A, Soltysiak J. Physical training, bradycardia, and autonomic nervous system. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 1973. 32:251–256.

14. Patil RD, DiCarlo SE, Collins HL. Acute exercise enhances nitric oxide modulation of vascular response to phenylephrine. Am J Physiol. 1993. 265:H1184–H1188.

15. Delp MD, Laughlin MH. Time course of enhanced endothelium-mediated dilation in aorta of trained rats. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1997. 29:1454–1461.

16. Green D, Cheetham C, Mavaddat L, Watts K, Best M, Taylor R, O'Driscoll G. Effect of lower limb exercise on forearm vascular function: contribution of nitric oxide. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002. 283:H899–H907.

18. Erbs S, Linke A, Hambrecht R. Effects of exercise training on mortality in patients with coronary heart disease. Coron Artery Dis. 2006. 17:219–225.

19. Nurnberger J, Dammer S, Opazo Saez A, Philipp T, Schafers RF. Diastolic blood pressure is an important determinant of augmentation index and pulse wave velocity in young, healthy males. J Hum Hypertens. 2003. 17:153–158.

20. Hirata K, Kawakami M, O'Rourke MF. Pulse wave analysis and pulse wave velocity: a review of blood pressure interpretation 100 years after Korotkov. Circ J. 2006. 70:1231–1239.

21. Takaki A, Ogawa H, Wakeyama T, Iwami T, Kimura M, Hadano Y, Matsuda S, Miyazaki Y, Matsuda T, Hiratsuka A, Matsuzaki M. Cardio-ankle vascular index is a new noninvasive parameter of arterial stiffness. Circ J. 2007. 71:1710–1714.

22. Heffernan KS, Jae SY, Fernhall B. Racial differences in arterial stiffness after exercise in young men. Am J Hypertens. 2007. 20:840–845.

23. Pannier B, Guerin AP, Marchais SJ, Safar ME, London GM. Stiffness of capacitive and conduit arteries: prognostic significance for end-stage renal disease patients. Hypertension. 2005. 45:592–596.

24. Tomiyama H, Koji Y, Yambe M, Shiina K, Motobe K, Yamada J, Shido N, Tanaka N, Chikamori T, Yamashina A. Brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity is a simple and independent predictor of prognosis in patients with acute coronary syndrome. Circ J. 2005. 69:815–822.

25. Jakicic JM, Winters C, Lang W, Wing RR. Effects of intermittent exercise and use of home exercise equipment on adherence, weight loss, and fitness in overweight women: a randomized trial. JAMA. 1999. 282:1554–1560.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download