Abstract

Endometrioid adenocarcinoma arising from endometriosis of the uterine cervix is rare in premenopausal woman. We describe here a patient with this condition and review the clinical and pathological features of these tumors. A 48-yr-old woman complaining of severe dysmenorrhea was referred for investigation of a pelvic mass. Total abdominal hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy were performed. Histological examination revealed an endometrioid adenocarcinoma directly adjacent to the endometriosis at the uterine cervix, with a transition observed between endometriosis and endometrioid adenocarcinoma. The patient was diagnosed as having endometrioid adenocarcinoma arising from endometriosis of the uterine cervix and underwent postoperative chemotherapy. Gynecologists and pathologists should be aware of the difficulties associated with a delay in diagnosis of endometrioid adenocarcinoma arising from endometriosis when the tumor presents as a benign looking endometrioma.

Endometriosis is defined as the presence of endometrial tissue outside the uterus. The most common sites affected are the ovaries, uterine ligaments, recto- and vesico-vaginal septae, pelvic peritoneum, cervix, labia and vagina. Malignant transformation of endometriosis may occur in up to 1% of women, with the most common site being the ovary (1). The risk of ovarian cancer increases among patients with a long history of ovarian endometrioma (2), and the malignant transformation of endometriosis may be affected by the hormonal changes associated with menopause (3, 4) Endometriosis is present in 10% to 15% of patients with ovarian cancer, with the most common extra-ovarian site of neoplastic transformation being the rectovaginal septum (5). Forty patients with endometriosis-associated intestinal tumors have been reported (6-7), but malignant transformation of endometriosis in the uterine cervix is exceedingly rare.

In this report, we describe a woman with endometrioid adenocarcinoma arising from endometriosis of the uterine cervix. In addition, we review the literature on this condition, and discuss the prognostic factors and the most appropriate therapeutic approaches.

A 48-yr-old woman complaining of severe dysmenorrhea was referred for investigation of a pelvic mass. She was otherwise well, was not taking hormone medication, and had a body mass index of 24.4 kg/m2. A cervical smear revealed benign cellular changes. Magnetic resonance imaging showed an image typical of an endometrial cyst of the uterine cervix, with high intensity in T1W1 and T2W1, a smooth surface, and shading. Adenomyosis was observed in the body of the uterus, but there was no evidence of enlarged lymph nodes or ascites (Fig. 1). Her serum concentration of CA125 was 359 U/mL (normal <35 U/mL). At the time of laparotomy, she had an enlarged uterus (12×7×6 cm3), which weighed 231 g, and her uterine cervix was enlarged to the size of an egg, with multiple round masses. Severe adhesion was observed, with endometrial tissue in the posterior wall of the uterus and the peritoneum and total posterior cul-de-sac obliteration. The left ovary was adherent to the posterior surface of the uterus, with a dark brownish cyst typical of an endometrial cyst. Total abdominal hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy with adhesiolysis were performed, and the specimens were submitted for frozen section analysis. The extra-ovarian lesions were electrically cauterized. Pathologic examination of the frozen sections suggested an adenocarcinoma arising from endometriosis in the cervical wall.

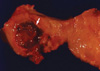

On gross examination, the cervical wall of the uterus contained a relatively well defined, cystic lesion filled with dark brown fluid, measuring 3×2.2×2.2 cm. The dark brown colored inner surface of the cyst showed multi-focal, papillary growing, solid and granular masses, measuring up to 0.8×0.8×0.5 cm (Fig. 2). Microscopically, these masses were composed of well differentiated endometrioid adenocarcinoma, which was directly adjacent to the epithelium of the endometriotic cyst of the cervical wall. Transitional areas between the glandular epithelium of the endometriosis and the endometrioid adenocarcinoma cells were observed. There was no invasion to the cervical stroma and no connection between the overlying mucosal epithelium of the endo-ectocervix and the epithelium of the endometriosis or the adenocarcinoma. A secretory phase endometrium measured 0.8 cm in thickness. There was no evidence of a primary endometrial or endocervical adenocarcinoma in the endocervix or endometrium (Fig. 3). Multiple foci of endometriosis were present within the posterior wall of the uterus and both ovaries. A serous cystadenoma was also present in the right ovary, measuring 4.0 cm in greatest dimension.

The expression of estrogen and progesterone receptors, p53 and c-erb B-2 was analyzed using paraffin immunohistochemistry. The area of endometrioid adenocarcinoma was positive for both estrogen and progesterone receptors. Weak expression of p53 and c-erbB2 (10-20% of nuclear staining) was observed in the carcinomatous area. The patient was diagnosed as having an endometrioid adenocarcinoma arising from endometriosis of the uterine cervix. Following recovery from surgery, she was treated with six courses of chemotherapy, consisting of cyclophosphamide 600 mg/m2 and cisplatin 50 mg/m2 every 4 weeks.

At the present time, she has been clinically free of disease for 24 months since undergoing surgery.

Endometriosis of the cervix is generally regarded as a rare lesion, but its incidence has been as high as 2.4% in some series (8). Previous trauma to the cervix may contribute to this condition. For example, cervical endometriosis has been observed in 43% of postconization hysterectomy specimens obtained from patients with cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) recurrence and other conditions (not endometriosis) (9). Therefore, the increasing incidence of invasive cervical procedures may increase the incidence of endometriosis. Cervical smears taken from most patients with cervical endometriosis have shown glandular cellularity (10, 11). In contrast, a cervical smear taken from our patient before exploration showed normal features. There was no invasion to the stroma of the cervix, or to the mucosal layer of the endocervix or exocervix.

Neoplastic transformation is a rare complication of endometriosis, documented in 0.3-0.8% of patients with ovarian endometriosis (7). Of 147 women with pelvic endometriosis, only one had ovarian cancer arising from the endometriosis (0.7%) (12). The risk of cancer arising from pre-existing endometriosis has been estimated at 0.7% to 1.0% (1). Of neoplasms complicating endometriosis, 75% arise in the ovaries, with the majority (almost 70%) being of endometrioid type.

Malignant ovarian tumors have been documented in women with endometriosis. Endometriosis-associated ovarian cancer (EAOC) usually occurs in younger women, has favorable outcomes, and appears as either a low-grade tumor of endometrioid cell type or as a clear cell tumor. As the pathologic features of "atypical endometriosis" may constitute a precancerous state, women with atypical endometriosis may be at an increased risk of developing EAOC. Malignant changes have also been diagnosed in extragonadal endometriosis. For example, a survey of 45 extragonadal malignancies associated with endometriosis in 1977 found that 16 (36%) were in the rectovaginal area, 5 (11%) in the colorectal area, 4 (9%) each in the bladder and vagina, 3 (7%) in the pelvic ligaments, and 2 (4%) each in the umbilicus, cervix, and fallopian tube (13). A more recent survey of 27 malignancies associated with endometriosis found that 17 (62%) were in the ovary, 3 (11%) in the vagina, 2 (7%) each in the fallopian tube or mesosalpinx, pelvic sidewall, and colon, and 1 (4%) in the parametrium (14); this report, however, did not include cervical malignancies associated with endometriosis. Malignant transformation of extra-ovarian endometriosis is thought to account for approximately 25% of all malignant transformations of endometriosis (1, 15).

Because of the rarity of malignant transformation of endometriosis at extraovarian sites, including the cervix, it is difficult to design an optimal surgical procedure. When feasible, however, primary surgical treatment should consist of complete resection of all disease containing tissue. Gross lesions in the pelvis should be surgically staged (1). Although postoperative treatment has not been clearly defined, 70% of these patients have been reported to receive chemotherapy or radiotherapy after first line surgery (1, 15).

The 5-yr survival rate for patients with estrogen-stimulated endometriosis-associated neoplasms arising at all sites has been reported to be 82% (1). Moreover, patients with endometrioid adenocarcinoma coexisting with endometriosis have a favorable prognosis (16).

To classify a malignancy as arising from endometriosis, strict histopathologic criteria need to be met (17). These include the demonstration of cancer arising in the tissue and not invading it from another source, and the presence of tissue resembling endometrial stroma surrounding the epithelial glands. Microscopic endometriosis contiguous with the malignant tissue should also be demonstrated. Our patient met all these diagnostic criteria.

The risk factors for malignant transformation in endometriosis are poorly defined. Estrogen can stimulate the growth of ectopic endometrial tissue. Thus, if any ovarian tissue remains following a hysterectomy, the disease is likely to recur in as many as 40% of women after 5 yr (6, 18). In addition, an association has been noted between unopposed estrogen therapy and the development of endometrioid or clear cell epithelial ovarian tumors (19, 20). Of 21 women with extraovarian cancers arising in endometriosis, 13 (62%) had received hormone replacement therapy (HRT) (15). In contrast, only 10% of other groups of patients, including those with ovarian cancer arising within the endometriosis, ovarian cancer with adjacent endometriosis and ovarian cancer with incidental endometriosis, had received HRT, with the majority of the latter receiving unopposed estrogen. In addition, tamoxifen therapy has been associated with endometriosis and the exacerbation of endometriotic foci in postmenopausal women (21), and obesity may affect tumor development (22). However, the body mass index of our patient was 24.4 kg/m2 and she had no previous history of estrogen or tamoxifen use. Also, our patient was 48 yr old and was premenopausal. Of three women with malignant tumors arising in endometriosis, 2 showed loss of ER and PR expression, suggesting that these tumors lose hormonal responsiveness as a result of malignant transformation (20). In contrast, the tumors in our patient showed consistent ER and PR expression, and she had no history of exposure to unopposed estrogen. These findings suggest that the loss of hormonal responsiveness did not play a part in the malignant transformation of endometriosis in our patient.

The increased association of HRT use with extraovarian cancer arising in endometriosis raises interesting questions that should prompt further investigation. Patients with endometrial cysts of the pelvic organs associated with high levels of serum CA125 should be managed with special care, even premenopausal women with no history of hormone therapy. Further work is required to determine whether the differences translate into a causal relationship. In conclusion, we present an extremely rare case of endometriosis-associated adenocarcinoma of the uterine cervix in a premenopausal woman. The clinical behavior of these tumors is unpredictable and long-term follow-up is essential in all patients. Additional case reports and prospective studies are needed to determine optimal treatment options to improve patient prognosis.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 1MRI findings of the patient. On T1, T2W sagittal images (A, B), showing multiple round masses of variable size on the uterine cervix (arrows). Adenomyosis was observed in the body of the uterus, but no enlarged lymph nodes or ascites was observed. |

| Fig. 3Histopathological findings. (A) Dilated endocervical glands in the cervix. There was no evidence of adenocarcinoma or connection with the endometriotic cyst (H&E, ×40). (B) Direct continuity was observed from the endometriosis (left upper) to the endometrioid adenocarcinoma (right side) in the cervix (H&E, ×100). (C) High-power view of endometrioid adenocarcinoma in the cervix (H&E, ×400). |

References

1. Heaps JM, Nieberg RK, Berek JS. Malignant neoplasms arising in endometriosis. Obstet Gynecol. 1990. 75:1023–1028.

2. Brinton LA, Gridley G, Persson I, Baron J, Bergqvist A. Cancer risk after a hospital discharge diagnosis of endometriosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997. 176:572–579.

3. Bergqvist A, Rannevik G, Thorell J. Estrogen and progesterone cytosol receptor concentration in endometriotic tissue and intrauterine endometrium. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand Suppl. 1981. 101:53–58.

4. Gould SF, Shannon JM, Cunha GR. Nuclear estrogen binding sites in human endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 1983. 39:520–524.

5. Mostoufizadeh M, Scully RE. Malignant tumors arising in endometriosis. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1980. 23:951–963.

6. Jones KD, Owen E, Berresford A, Sutton C. Endometrial adenocarcinoma arising from endometriosis of the rectosigmoid colon. Gynecol Oncol. 2002. 86:220–222.

7. Kurman RJ, Craig JM. Endometrioid and clear cell carcinoma of the ovary. Cancer. 1972. 29:1653–1664.

8. Veiga-Ferreira MM, Leiman G, Dunbar F, Margolius KA. Cervical endometriosis: facilitated diagnosis by fine needle aspiration cytologic testing. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1987. 157(4 Pt 1):849–856.

9. Ismail SM. Cone biopsy causes cervical endometriosis and tuboendometrioid metaplasia. Histopathology. 1991. 18:107–114.

10. Baker PM, Clement PB, Bell DA, Young RH. Superficial endometriosis of the uterine cervix: a report of 20 cases of a process that may be confused with endocervical glandular dysplasia or adenocarcinoma in situ. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 1999. 18:198–205.

11. Hanau CA, Begley N, Bibbo M. Cervical endometriosis: a potential pitfall in the evaluation of glandular cells in cervical smears. Diagn Cytopathol. 1997. 16:274–280.

12. Nishida M, Watanabe K, Sato N, Ichikawa Y. Malignant transformation of ovarian endometriosis. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2000. 50:Suppl 1. 18–25.

13. Brooks JJ, Wheeler JE. Malignancy arising in extragonadal endometriosis: a case report and summary of the world literature. Cancer. 1977. 40:3065–3073.

14. Leiserowitz GS, Gumbs JL, Oi R, Dalrymple JL, Smith LH, Ryu J, Scudder S, Russell AH. Endometriosis-related malignancies. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2003. 13:466–471.

15. Modesitt SC, Tortolero-Luna G, Robinson JB, Gershenson DM, Wolf JK. Ovarian and extraovarian endometriosis-associated cancer. Obstet Gynecol. 2002. 100:788–795.

16. Sainz de la Cuesta R, Eichhorn JH, Rice LW, Fuller AF Jr, Nikrui N, Goff BA. Histologic transformation of benign endometriosis to early epithelial ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 1996. 60:238–244.

17. Yantiss RK, Clement PB, Young RH. Neoplastic and pre-neoplastic changes in gastrointestinal endometriosis: a study of 17 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000. 24:513–524.

18. Wheeler JM, Malinak LR. Recurrent endometriosis: incidence, management, and prognosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1983. 146:247–253.

19. Purdie DM, Bain CJ, Siskind VJ, Russell P, Hacker NF, Ward BG, Quinn MA, Green AC. Hormone replacement therapy and risk of epithelial ovarian cancer. Br J Cancer. 1999. 81:559–563.

20. Reimnitz C, Brand E, Nieberg RK, Hacker NF. Malignancy arising in endometriosis associated with unopposed estrogen replacement. Obstet Gynecol. 1998. 71(3 Pt 2):444–447.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download