Abstract

Fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva (FOP; OMIM 135100) is a rare but extremely disabling genetic disorder of the skeletal system, and is characterized by the progressive development of ectopic ossification of skeletal muscles and subsequent joint ankylosis. The c.617G>A; p.R206H point mutation in the activin A type I receptor (ACVR1) gene has been reported to be a causative mutation of FOP. In the present study, mutation analysis of the ACVR1 gene was performed in 12 patients diagnosed or suspected to have FOP. All patients tested had a de novo heterozygous point mutation of c.617G>A; p.R206H in ACVR1. Mutation analysis confirmed a diagnosis of FOP in patients with ambiguous features, and thus, could be used for diagnostic purposes. Early confirmation through mutation analysis would allow medical professionals to advise on the avoidance of provoking events to delay catastrophic flare-ups of ectopic ossifications.

Fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva (FOP; OMIM 135100) is a rare genetic disorder characterized by the progressive development of ectopic ossification of the skeletal muscles and subsequent joint stiffness. The worldwide prevalence of FOP is estimated to be approximately 1/2,000,000 (1). The majority of FOP cases are sporadic, but in familial cases, inheritance is autosomal-dominant with variable expression (2). Children with FOP appear normal at birth except congenital

malformations of the great toes or phalanges (3, 4). However, in general, sporadic episodes of painful soft tissue swellings (flare-ups) occur during the first decade of life (3). Even minimal trauma such as minor soft tissue injuries, muscle overstretching, overexertion and fatigue, intramuscular injections, falls, or influenza-like illnesses may lead to episodic flare-ups (1, 4). These soft tissue nodules rarely regress spontaneously, and usually they rapidly mature through an endochondral ossification to form normal lamellar bone (3, 5). Heterotopic ossification in FOP is not random but proceeds in a direction that is axial to appendicular, cranial to caudad, and proximal to distal (3). The diaphragm, extraocular, cardiac, and smooth muscles are characteristically spared from ossification (3, 6).

FOP is diagnosed based on clinical and radiographic findings. When established ectopic ossification has been confirmed in a FOP patient, no remedies are available to improve functional capability. Thus, early diagnosis and the avoidance of provoking events is essential to delay the onset of catastrophic restriction of motion. Nonetheless, the rates of diagnostic errors and of inappropriate invasive medical procedures are astonishing, which is probably caused by a lack of physician awareness (7).

Recently, FOP was found to be caused by a heterozygous point mutation of c.617G>A; p.R206H in the gene coding activin A type I receptor (ACVR1) on chromosome 2q23-24 (8). This mutation is reported to be recurrent regardless of races (8-10). To the best of our knowledge, the c.617G>A mutation is the only one that has been associated with FOP to date.

Korean familial FOP patients were included in the previous multi-center linkage analysis study to locate this disease locus to ACVR1 gene (8). In the present study, we conducted mutation analysis of c.617G>A in ACVR1 in sporadic Korean patients who were clinically and radiologically diagnosed or suspected to have FOP.

Twelve patients were included in this study. The phenotypes of the patients are summarized in Table 1. Ten patients had definite clinical manifestations of FOP, i.e., progressive ectopic ossification with resultant joint ankylosis (Fig. 1). Detailed clinical manifestations in some patients (case 7, 8, and 10) have been reported previously (11). Two patients (cases 1 & 2) showed ambiguous clinical features. An 8-yr old boy (case 1) was referred under a diagnosis of hereditary multiple exostosis. He did not have any restriction of joint motion except for limitation of terminal flexion in both elbow joints. No soft tissue mass or ectopic ossification was observed in this patient except for an osteochondroma-like bony spur on the right distal humerus. However, he was suspected to have FOP due to big toe anomalies. A 15-yr-old girl (case 2) visited complaining of in-toeing gait and calf pain after exercise. Although having mild flexion contractures on both hip and knee joints, she was athletically active. No ectopic ossification observed except for osteochondroma-like bony spurs on both distal femora (Fig. 2A). Big toe anomalies (Fig. 2B) and the 5th finger symphalangism lead us to suspect FOP. The parents recalled that a subcutaneous painless migrating scalp nodule had been detected when she was 6 months old, which spontaneously resolved in 2 weeks. Mutation analysis revealed heterozygous c.617G>A; p.R206H mutation in ACVR1, and she started to experience series of flare-up at age of 16 yr.

Peripheral blood was obtained from all patients and, if possible, from their parents (case 1, 2, and 6) after obtaining informed consent. Genomic DNA was extracted from circulating leukocytes using standard procedures. A portion of genomic DNA encompassing exon 4 of ACVR1 was amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using specific primers (5'-CCAGTCCTTCTTCCTTCTTCC-3', sense and 5'-AGCAGATTTTCCAAGTTCCATC-3', antisense) (8). PCR products were sequenced directly using an ABI Prism 3700 automated sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, U.S.A.). Results were further verified by restriction endonuclease digestion of PCR products using Cac8I (New England Biolabs, Beverly, MA, U.S.A.) and HphI (New England

Biolabs).

DNA sequence analysis demonstrated the invariable presence of a heterozygous point mutation of c.617G>A in all ten patients with obvious clinical manifestations (Fig. 3A). The mutation was not detected in any of their family members tested. In addition to direct DNA sequence analysis, the

presence of c.617G>A mutation was also verified by restriction endonuclease digestion (Fig. 3B). The c.617G>A ACVR1 mutation eliminates a Cac8I site and forms a new HphI site. The PCR product of 350 bp from the G allele (control-parents) was digested by Cac8I and produced three bands (139, 114, and 97 bp), whereas the A allele (FOP patients) appeared as two bands (253 and 97 bp). For HphI, PCR products of controls were not digested (one band) whereas bands of 228 and 122 bp, corresponding to the A allele, were detected for all FOP patients (8).

In two patients (case 1 & 2) with ambiguous clinical features, DNA sequence analysis demonstrated and restriction endonuclease digestion analysis confirmed the presence of a heterozygous de novo c.617G>A mutation.

This is the first report on mutation analysis conducted in sporadic Korean FOP patients. It shows that all 12 sporadic FOP patients had invariable heterozygous mutation of c.617G>A in ACVR1.

FOP is an extremely rare disorder and most cases are sporadic (1). Clinical manifestations of typical FOP are considerably uniform, i.e., usually ectopic ossifications occur and progress during the first decade of life and most patients are wheelchair bound by the end of the second decade (1, 3, 6). Delayed onset of ossification after age 15 yr is quite rare, although reports have been issued concerning mild cases with a late onset of ossification and unusually slow progression that remained ambulatory till their mid-forties; however, these cases were not confirmed by mutational analysis (12). This diverse clinical course causes diagnostic and counseling difficulties in patients with atypically mild FOP patients.

However, diagnosis of FOP can be erratic before the onset of established ectopic ossification (7, 11). Diagnostic errors and inappropriate medical procedures, for example, attempts to remove the heterotopic bone, may lead to explosive new bone formations and can aggravate the natural history of FOP (7). Thus, early diagnosis and confirmation of FOP is essential if such iatrogenic hazards are to be avoided.

To achieve early diagnosis before the flare-ups of ectopic ossification, great toe abnormalities and a history of migrating pre-osseous soft tissue mass on the scalp, neck or back during infancy or early childhood may be informative (11, 13). In particular, great toe abnormality is one of the most stringent and unambiguous features of FOP patients, and usually presents as short, malformed great toes with or without valgus deviation (6). All patients in the present study also showed great toe anomaly. However, these clinical manifestations without ectopic ossification only suggest diagnosis of FOP and cannot confirm it.

The variable clinical manifestation of FOP argues against the homogeneity of the FOP mutation (9). Shore et al. (8) reported that the c.617G>A ACVR1 mutation was not identified in a family who showed ambiguous FOP features. However, in the present study, mutational analysis confirmed the diagnosis even in those with exceptionally mild phenotype, e.g., in case 2. In a study using in-silico modeling of wild-type and mutant ACVR1, substitution with histidine (p.R207H), and only histidine, created a pH-sensitive switch within the activation domain of the receptor that lead to ligand-indepenent activation of ACVR1 in FOP (1). The mechanism affecting the severity of disease progression remains to be elucidated. However, our findings demonstrate that mutational analysis of the ACVR1 is helpful for confirming or excluding a diagnosis of FOP in clinically ambiguous patients. Furthermore, we recommend mutation analysis in young patients with the early stigma of FOP, e.g., great toe anomaly and a migrating mass on the scalp, neck or back during infancy or early childhood, to allow patients to avoid provoking events during earlier life.

The incidence of human spontaneous mutation increases according to parental age, especially paternal age (14). In the present study, the mean paternal and maternal age was 34 and 31, respectively. Although paternal ages were over thirties in all cases, we could not determine the effect of parental age on ACVR1 mutation.

In conclusion, the present study shows that the de novo c.617G>A; p.R206H heterozygous point mutation in the ACVR1 is present in all sporadic Korean FOP patients examined. Moreover, mutation analysis confirms a diagnosis of FOP in patients with ambiguous features, which enable the medical personnel to give early appropriate medical advice concerning the prevention of provoking events with hope for delay or prevention of catastrophic flare-ups of ectopic ossifications.

Figures and Tables

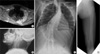

Fig. 1

Radiographic findings of FOP patients with unambiguous clinical features. Infiltration of paraspinal muscles mimicking a tumorous condition (A), ossification around the neck (B), thoracolumbar spine (C), and left thigh, which caused permanent loss of motion (D).

Fig. 2

Radiographic findings suggestive of FOP in a patient with ambiguous clinical features (case 2). (A) This patient showed no ectopic ossification but an osteochondroma-like bony spurs were observed on both distal femora, (B) Big toe abnormalities in this patient showed a slanting of metatarso-phalangeal joint (hallux valgus deformity).

Fig. 3

Mutation analysis of the ACVR1 in FOP patients with definite clinical manifestations. (A) Direct sequencing of the PCR products of the ACVR1 showed the presence of the c.617G>A mutation. R=adenine or guanine, (B) Restriction endonuclease digestion of the PCR product (350 bp). The G allele (control) was digested by Cac8I to produce three bands, whereas the A allele appeared as two bands. Because FOP patients were heterozygous for this mutation, the 139 bp and 114 bp bands were also presented. The PCR product not digested with HphI corresponds to the G allele (control) in contrast to digested products corresponding to the A allele (FOP).

References

1. Groppe JC, Shore EM, Kaplan FS. Functional modeling of the ACVR1 (R206H) mutation in FOP. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2007. 462:87–92.

2. Shore EM, Feldman GJ, Xu M, Kaplan FS. The genetics of fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva. Clin Rev Bone Miner Metab. 2005. 3:201–204.

3. Cohen RB, Hahn GV, Tabas JA, Peeper J, Levitz CL, Sando A, Sando N, Zasloff M, Kaplan FS. The natural history of heterotopic ossification in patients who have fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva. A study of forty-four patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1993. 75:215–219.

4. Kaplan FS, Glaser DL, Shore EM, Deirmengian GK, Gupta R, Delai P, Morhart R, Smith R, Le Merrer M, Rogers JG, Connor JM, Kitterman JA. The phenotype of fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva. Clin Rev Bone Miner Metab. 2005. 3:183–188.

5. Kaplan FS, Tabas JA, Gannon FH, Finkel G, Hahn GV, Zasloff MA. The histopathology of fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva. An endochondral process. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1993. 75:220–230.

6. Connor JM, Evans DA. Fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva. The clinical features and natural history of 34 patients. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1982. 64:76–83.

7. Kitterman JA, Kantanie S, Rocke DM, Kaplan FS. Iatrogenic harm caused by diagnostic errors in fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva. Pediatrics. 2005. 116:e654–e661.

8. Shore EM, Xu M, Feldman GJ, Fenstermacher DA, Cho TJ, Choi IH, Connor JM, Delai P, Glaser DL, LeMerrer M, Morhart R, Rogers JG, Smith R, Triffitt JT, Urtizberea JA, Zasloff M, Brown MA, Kaplan FS. A recurrent mutation in the BMP type I receptor ACVR1 causes inherited and sporadic fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva. Nat Genet. 2006. 38:525–527.

9. Nakajima M, Haga N, Takikawa K, Manabe N, Nishimura G, Ikegawa S. The ACVR1 617G>A mutation is also recurrent in three Japanese patients with fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva. J Hum Genet. 2007. 52:473–475.

10. Lin GT, Chang HW, Liu CS, Huang PJ, Wang HC, Cheng YM. De novo 617G-A nucleotide mutation in the ACVR1 gene in a Taiwanese patient with fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva. J Hum Genet. 2006. 51:1083–1086.

11. Choi IH, Chung CY, Cho TJ, Lee DY, Suk SI, Kim WJ, Cho HO, Lee CS, Yoo HW, Yun YH. Fibrodysplasia Ossificans Progressiva. J Korean Orthop Assoc. 1998. 33:1069–1075.

12. Janoff HB, Tabas JA, Shore EM, Muenke M, Dalinka MK, Schlesinger S, Zasloff MA, Kaplan FS. Mild expression of fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva: a report of 3 cases. J Rheumatol. 1995. 22:976–978.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download