Abstract

For diagnosis and management of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), the easily administered assessment tool is essential. Structured Interview for PTSD (SIP) is a validated, 17-item, simple measurement being used widely. We aimed to develop the Korean version of SIP (K-SIP) and investigated its psychometric properties. Ninety-three subjects with PTSD, 73 subjects with mood disorder or anxiety disorder as a psychiatric control group, and 88 subjects as a healthy control group were enrolled in this study. All subjects completed psychometric assessments that included the K-SIP, the Korean versions of the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS) and other assessment tools. The K-SIP presented good internal consistency (Cronbach's α=0.92) and test-retest reliability (r=0.87). K-SIP showed strong correlations with CAPS (r=0.72). Among three groups including PTSD patients, psychiatric controls, and normal controls, there were significant differences in the K-SIP total score. The potential cut-off total score of K-SIP was 20 with highest diagnostic efficiency (91.9%). At this point, the sensitivity and specificity were 95.5% and 88.4%, respectively. Our result showed that K-SIP had good reliability and validity. We expect that K-SIP will be used as a simple but structured instrument for assessment of PTSD.

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a chronic and disabling disorder, characterized by specific symptoms that develop following exposure to trauma where the person's response involves intense fear, helplessness or horror (1). Nowadays, PTSD is not merely a disease confined to an individual patient, but a suffering which makes social impacts and requires national structured system preparing for disaster, especially in highly industrialized countries.

Since PTSD was first introduced in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, third edition (DSM-III) (2), a number of interviewer-administered scales have been developed for the assessment of symptoms of PTSD. These structured interview-based measures of PTSD include the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID) (3), the Clinician Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS) (4), the PTSD Interview (5), Structured Interview for PTSD (SIP) (6), Short PTSD rating inventory (SPRINT) (7), and the Posttraumatic Stress Scale (8). And some self-rating assessment tools such as Davidson Trauma Scale (DTS) (9), Impact of event scale-revised (IES-R) (10) are also have been developed and used widely. All of these scales show good psychometric reliability and validity and are comprehensive in assessing the core symptoms of PTSD. Among these, CAPS, a most comprehensive and psychometrically sound interview-based measurement is only one standardized in Korea (11). However, CAPS has a major limitation that it takes more than one hour and not easily applicable for clinical practice or emergent situation such as disaster. Therefore, we need the more practical instrument for screening, diagnosing, and assessing treatment effect in relative short time, SIP is one of the adequate measures for that purpose.

SIP was first developed by Davidson et al. (12) in 1989 with reference to DSM-III criteria and modified several time for assessment of diagnosis, treatment effect, and symptom severity (13). This scale comprises 17 items reflective of the DSM-IV criteria for PTSD. So this can be readily administered for diagnosis according to DSM-IV in about 20 min. Cronbach's α, a measure of internal consistency, was 0.80, and correlation with other measures of PTSD, depression, and anxiety were also high (6).

In this study, we aimed to develop and validate the Korean version of SIP (K-SIP). First, we performed the translation of SIP into Korean language while maintaining its basic structure. And we figured out the validity and reliability of K-SIP for testing the usefulness in Korean patients.

Total of 254 subjects were recruited from 18 medical institutions in all states and territories of Korea, from January 2006 until December 2006. Among those are 93 subjects with PTSD, 73 subjects with mood disorder or anxiety disorder as a psychiatric control group, and 88 subjects as a healthy control group. All of the subjects were between 18 and 65 yr of age. PTSD and other psychiatric disorders were diagnosed by the MINI International Neuropsychiatric Interview using the criteria of the DSM-IV (14, 15). The diagnoses of subjects in the psychiatric control included major depressive disorder (N=54), panic disorder (N=7), generalized anxiety disorder (N=12). There were no significant difference in mean age and gender among PTSD group, psychiatric control group and healthy control group.

Each of the healthy controls demonstrated that they did not have a lifetime history of psychiatric and medical disorders in a semi-structured interview. Each of the subjects provided informed consents for their participation in this study after the procedure had been fully explained and the institutional review board approved this study.

First of all, the SIP was translated in Korean by two psychiatrists and one psychologist, and any English phrases that were difficult to understand were translated into Korean after consulting a Korean professor of English literature. Then, the Korean SIP was back-translated by a person bilingual in English and Korean, to validate the translation, and the back-translated version was reviewed. After obtaining permission from the original author of the translated version, we established the final Korean translation version of the SIP (K-SIP).

The Korean version of CAPS was used to assess the convergent validity of the K-SIP. The CAPS is a comprehensive, psychometrically sound, structured clinical interview designed to assess adults for the seventeen symptoms of PTSD outlined in the DSM-IV along with five associated features (guilt, dissociation, derealization, depersonalization, and reduction in awareness of surroundings). It consisted of CAPS-1 and CAPS-2, which were designed to assess the current or lifetime PTSD status and PTSD symptoms experienced during the previous week, respectively. The Korean version of CAPS has excellent internal consistency, with Cronbach's α-coefficient of 0.95 (11). In this study, we only used the CAPS-2 in which the assessment period corresponded to that of K-SIP.

The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) and the Spielberger State Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) was also performed to assess the correlations of peripheral or related aspects of PTSD and K-SIP. The BDI, a 21-item self-administered questionnaire, was developed to assess the severity of subjective depressive symptoms, and the STAI, which is a self-reporting questionnaire, was designed to evaluate the severity of the anxiety symptoms and is composed of 20 questions for anxiety and 20 questions for trait anxiety (16, 17). The Korean version of the BDI demonstrated good psychometric properties, and its internal consistency coefficient was reported to be 0.85 (18). The Korean version of STAI has previously been shown to exhibit excellent psychometric properties, and its internal consistency has been reported as having a Cronbach's αcoefficient of 0.91 (19).

The raters in this study were experienced board-certificated psychiatrists who participated in formal consensus meetings concerning the use of the K-SIP and the Korean version of CAPS. The consensus meetings consisted of observing the administration of the evaluations by an experienced supervisory psychiatrist and videotaped administrations featuring standard PTSD patients. The inter-rater reliability values of the K-SIP and the Korean version of CAPS were high, with intra-class correlation coefficients of 0.85 and 0.76, respectively.

Group comparisons were performed using the analysis of variance (ANOVA) and χ2 analyses to compare the quantitative and categorical variables, respectively. Internal consistency was assessed using Cronbach's α. Test-retest reliability was calculated by means of the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC). The inter-rater reliability was also analyzed on the basis of ICC. The concurrent validity between the K-SIP and other measures were evaluated using Pearson correlation coefficients. ANOVA and Tukey's post hoc test were applied to identify the between-group difference by the severity measured by the K-SIP. The factorial validity of the K-SIP was examined using an unrotated principal components factor analysis in the PTSD patients. The sensitivity, specificity, predictive values, and diagnostic efficiency were calculated according to the standard formulae. We analyzed a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve to obtain the optimal cut-off score to detect PTSD in all subjects. All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS for Windows, version 10.0.

The mean ages of the PTSD, psychiatric control, and normal control group were 44.9 (SD=15.7), 44.6 (SD=14.6), and 43.0 (SD=13.2) years, respectively. The numbers of males in the three groups were 48 (51.6%), 28 (37.5%), and 50 (56.8%), respectively. No significant differences were found for age (F=1.303, p=0.274) or gender ratio (χ2=5.677, p=0.059) between the three groups. There was no significant difference in marital status, although a significant difference in economic status was found among the three groups (χ2=10.480, p=0.033).

The mean duration of symptoms in the PTSD group was 5.4 (SD=10.9; range=0.1-52.0) yr. The worst traumas experienced in the PTSD group were serious accidents, such as automobile or man-made disasters (N=54, 58.1%), assault (N=11, 11.8%), combat experience (N=7, 7.5%), imprisonment (N=4, 4.3%), sexual abuse (N=3, 3.2%), disease (N=2, 2.2%), and witnessing an accident (N=1, 1.1%).

Cronbach's α was used to evaluate the internal consistency of the K-SIP in 93 PTSD patients. The coefficient was 0.92 at baseline for the 17 items in K-SIP. Based on the criterion of 0.30 as an acceptable corrected item-total correlation (20), all 17 items performed adequately (range=0.45-0.76). (Table 1)

The test-retest reliability was examined by comparing the baseline K-SIP score with a K-SIP assessment performed 2 weeks later. The PTSD patients only included those who claimed that there was no change in their PTSD symptoms and agreed to a second K-SIP assessment. Among the 93 PTSD patients, 42 subjects were recruited for the evaluation of the test-retest reliability. The test-retest reliability was determined to be 0.87 (p<0.001).

The total scores±standard error (SE) of K-SIP in the PTSD group, the psychiatric controls and normal controls were 39.82±1.34, 15.73±2.32, and 2.44±4.21, respectively. These values significantly varied by ANOVA (overall F=186.14, p<0.001). The Tukey's post-hoc test showed that there were significant differences among the three groups. These results showed a good construct validity of the K-SIP

For validity to assess the core symptoms of PTSD, concurrent validity of K-SIP was assessed by comparison with CAPS. Total K-SIP score was highly correlated with weekly CAPS score (r=0.72, p<0.001; N=48). Concurrent validity was also assessed being compared to other measures that address peripheral or related aspects of PTSD. The total K-SIP score was correlated with BDI (r=0.61, p<0.001; N=82), the state anxiety of STAI (r=0.28, p=0.010; N=84), and trait anxiety of STAI (r=0.40, p<0.001; N=85). Thus, the correlation of K-SIP was strong with CAPS, and relatively weak with STAI, and intermediate with BDI (Table 2).

The explorative factor analysis with varimax rotation on the items of the K-SIP for 93 subjects from PTSD group showed that there were three factors that explained 61.71% of the total variance. Factor I accounted for 43.57% of the variance (eigenvalue, 7.41) and was interpreted as numbness and depression, with loadings for each item ranging from 0.58 to 0.78. Factor II accounted for 10.63% of the variance (eigenvalue, 1.81) loaded on avoidance and distress at exposure to reminder of events. Factor III (eigenvalue, 1.28) loaded on hyperarousal (Table 3).

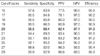

An ROC analysis was conducted to obtain the cut-off score on the K-SIP for the diagnosis of PTSD. The sensitivity, specificity, predictive values, and diagnostic efficiency were calculated for every possible K-SIP cut-off score. Table 4 shows ten different threshold scores and their corresponding sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive values, and diagnostic efficiency. The highest diagnostic efficiency was found at a total score of 20, where the sensitivity and specificity were 95.5% and 88.4%, respectively.

The area under the ROC curve (AUC) is an overall index of the accuracy of the discrimination provided by the K-SIP. The AUC ranges from 0 to 1, with an AUC above 0.85 generally considered to be an indication of good diagnostic ability (21). The AUC of the K-SIP is 0.94 and its standard error is 0.019 (p<0.001). This AUC value confirmed the excellent diagnostic ability of the K-SIP.

We developed The Korean version of SIP, and test the reliability and validity in the Korean population. The original version of SIP was developed as one of several interview-based measures of PTSD for assessment of diagnosis, treatment effect, and symptoms severity (13). The SIP consists of 17 items according to the DSM-IV criteria for PTSD, supplemented by two measures of survival and behavioral guilt, which represent holdovers from the DSM-III criteria and which are felt to the phenomenologically important when present because they may have some bearing on treatment management and outcome (22). Each item is rated on a 0-4 scale and represents a composite of frequency, severity, and functional impairment. There is a maximum total score of 68 for the DSM-IV symptoms without guilt.

In our results, we found out that K-SIP presented good reliability and validity. Internal consistency of K-SIP indicated a Cronbach's α of 0.92 and this coefficient was within the optimal range considering that an ideal value of α should be between 0.70 and 0.90 (23). And this is consistent with the Cronbach's α of 0.80 in the original SIP (6). The test-retest reliability of K-SIP was determined to be 0.87 in the Pearson correlation and also consistent with 0.89 of the original SIP (6). The test-retest interval in this study was two weeks. In clinical settings, longer test-retest intervals mean greater possibilities of symptom changes. Most of the PTSD subjects assessed in this study were chronic types whose mean duration of symptoms was 4.9 yr, and all of the subjects claimed that there were no changes in their symptoms. However, some subjects refused to enter the retest due to painful experiences with individual stressors. Consequently, 42 PTSD subjects (45.2%) were enrolled in the test-retest study. The result of the test-retest reliability was quite good. Thus, we can conclude that the K-SIP showed good reliability as compared with the original SIP

In order to assess the concurrent validity, we compared the K-SIP total score with the weekly CAPS total score. The CAPS is widely used for the diagnosis of PTSD and is often considered the gold standard for the assessment of PTSD (24). The K-SIP and CAPS demonstrated a strong correlation in our results (r=0.72), which was comparable to that of original SIP (r=0.67) from the Davidson group who developed the scale (6). Thus, K-SIP as well as the original SIP might be more ideal for use in routine clinical or research assessments of PTSD considering that they performed similarly to the CAPS and took less time to administer than the CAPS. The correlation between K-SIP and other measures such as BDI and STAI was also significant. PTSD is easily comorbid with depressive and anxiety disorder, and PTSD symptoms are very often presented with depressive symptoms and anxiety. So, this correlation is not surprising. However, the correlation with other measures is weaker than that with CAPS, which shows that K-SIP is more useful and specific scale for PTSD.

The best diagnostic efficiency was 91.9% when the cut-off score of the K-SIP was 20 in this study, and this is similar with the original SIP (6). Sensitivity and specificity was very good as 95.5% and 88.4% when using 20 as the cut-off score. The determination of the optimal cut-off point for the diagnosis of a disorder of concern is an invaluable process in the validation study. However, the best cut-off point to achieve optimal sensitivity and specificity may have considerable variances from one clinical setting to another (25). The differences in the standard to define a case, the particular disorders included in the cases, the timing of the interview relative to the administration of the screening, the prevalence and severity of the disorder in the studied population and socioepidemiological variables such as age, gender, and education could be included as possible sources of variation in the threshold (26). There were also some variations between different cultures and even between different institutes within the same culture (27). Therefore, the optimal cut-off point of the scale may not be fixed in accordance with various situations.

The findings of this study have the following limitations. The sample sizes of the individual events were relatively small, thus making it difficult to draw any definite conclusions. In addition, most of the healthy controls and non-PTSD patients did not experience the traumatic event that was strictly met by DSM-IV diagnostic criterion A for PTSD. Instead, they recollected the most distressing traumatic event past one year and interviewed with a rater.

In conclusion, our findings demonstrate that the K-SIP had good psychometric properties and can be used as a reliable, valid, and timesaving tool to diagnose and assess PTSD. Further studies are needed to fully evaluate the K-SIP, including researches applying it to the general population and in a primary medical setting where the prevalence of PTSD is relatively low.

Figures and Tables

Table 1

The correlation between scores of each item and total score of K-SIP (Structured Interview for PTSD-Korean version)

Table 2

Pearson's correlations among K-SIP, CAPS, BDI, and STAI in the PTSD patients

*p<0.05 level of significance; †p<0.001 level of significance.

K-SIP, Structured Interview for PTSD-Korean version; CAPS, Clinicians Administered PTSD Scale; BDI, Beck Depression Inventory; STAI-S, State-Trait Anxiety Inventory-state anxiety subscale; STAI-T, State-Trait Anxiety Inventory-trait anxiety subscale.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by a grant of the Korean Academy of Anxiety Disorders, Korean Neuropsychiatric Association, and Korean Health 21 R & D Project, Ministry of Health and Welfare (A060273), and the Specific Research Program (M10644000013-06N4400-01310), Ministry of Science & Technology, Republic of Korea.

References

1. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 1994. 4rd ed. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association.

2. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 1980. 3rd ed. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association.

3. Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Gibbon M, First MB. Structured clinical interview for DSM-III-R (SCID). 1990. New York: Biometric Research Department, State Psychiatric Institute, New York.

4. Blake DD, Weathers FW, Nagy LM, Kaloupek DG, Gusman FD, Charney DS, Keane TM. The development of a clinician-administered PTSD scale. J Trauma Stress. 1995. 8:75–90.

5. Watson CG, Juba MP, Manifold V, Kucula T, Anderson PE. The PTSD interview: rationale descriptions, reliability, and concurrent validity of a DSM-III based technique. J Clin Psychol. 1991. 47:179–188.

6. Davidson JR, Malik MA, Travers J. The structured interview for PTSD (SIP): psychometric validation for DSM-IV criteria. Depress Anxiety. 1997. 5:127–129.

7. Conner KM, Davidson JR. SPRINT: a brief global assessment of post-traumatic stress disorder. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2001. 16:279–284.

8. Foa EB, Tolin DF. Comparison of PTSD symptom scale interview version and the clinician-administered PTSD scale. J Trauma Stress. 2000. 13:181–191.

9. Davidson JR, Book SW, Colket JT, Tupler LA, Roth S, David D, Hertzberg M, Mellman T, Beckham JC, Smith RD, Davison RM, Katz R, Feldman ME. Assessment of a new self-rating scale for post-traumatic stress disorder. Psychol Med. 1997. 27:153–160.

10. Horowitz M, Wilner N, Alvarez W. Impact of Event Scale: a measure of subjective stress. Psychosom Med. 1979. 41:209–218.

11. Lee BY, Kim Y, Yi SM, Eun HJ, Kim DI, Kim JY. A reliability and validity study of a clinician-administered PTSD scale. J Korean Neuropsychiatr Assoc. 1999. 38:514–522.

12. Davidson J, Smith RD, Kudler H. Validity and reliability of the DSM-III criteria for posttraumatic stress disorder. Experience with a structured interview. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1989. 177:336–341.

13. Solomon SD, Keane TM, Newman E, Kaloupek DG. Carlson EB, editor. Choosing self-report measures and structured interviews. Trauma Research Methodology. 1996. Lutherville, MD: Sidran;56–71.

14. Sheehan DV, Lecruiber Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, Hergueta T, Baker R, Dunbar GC. The MINI international neuropsychiatric interview (MINI): the development and validation of a structured interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998. 59:Suppl 20. 22–33.

15. Yoo SW, Kim YS, Noh JS, Oh KS, Kim CH, Nam KK, Chae JH, Lee GC, Jeon SI, Min KJ, Oh DJ, Joo EJ, Park HJ, Choi YH, Kim SJ. Validity of Korean Version of the MINI international neuropsychiatric interview. Anxiety Mood. 2006. 2:50–55.

16. Beck AT, Steer RA. BDI, Beck depression inventory. 1987. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corp.

17. Spielberger CD, Gorsuch RL. State-trait anxiety inventory. 1983. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press.

18. Rhee MK, Lee YH, Park SH, Sohn CH, Chung YJ, Hong SK, Lee BK, Chang P, Yoon AR. A standardization study of Beck depression inventory I; Korean version (K-BDI): reliability and factor analysis. Korean J Psychopathol. 1995. 4:77–95.

19. Hahn DW, Lee CH, Chon KK. Korean adaptation of Spielberger's STAI (K-STAI). Korean J Health Psychol. 1996. 1:1–14.

20. Nunnally JC, Bernstein IH. Psychometric theory. 1994. 3rd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill.

22. Davidson JR, Kudler HS, Saunders WB, Erickson L, Smith RD, Stein RM, Lipper S, Hammett EB, Mahorney SL, Cavenar JO Jr. Predicting response to amitriptyline in posttraumatic stress disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1993. 150:1024–1029.

23. Nunnally JC. Introduction to Psychological Measurement. 1978. New York: McGraw-Hill, NY.

24. Weathers FW, Keane TM, Davidson JR. Clinician-administered PTSD scale: a review of the first ten years of research. Depress Anxiety. 2001. 13:132–156.

25. Chen CH, Shen WW, Tan HK, Chou JY, Lu ML. The validation study and application of stratum-specific likelihood ratios in the Chinese version of SPAN. Compr Psychiatry. 2003. 44:78–81.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download