Abstract

Urticarial vasculitis is characterized clinically by urticarial skin lesions and histologically by leukocytoclastic vasculitis. Hypocomplementemic urticarial vasculitis is associated with connective tissue diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). We report a case of urticarial vasculitis that preceded manifestations of SLE.

Urticarial vasculitis is characterized by recurrent episodes of urticaria with biopsy evidence of leukocytoclastic vasculitis (1). Although urticarial vasculitis is frequently idiopathic, it has been reported to be associated with infection, malignancy, certain drugs, and connective tissue diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and Sjogren's syndrome (2). Here, we report a case wherein urticarial vasculitis preceded the manifestations of SLE.

In August 2005, a 50-yr-old woman visited our hospital with a 3-month history of recurrent multiple urticarial rashes and wheals on the face, trunk and back. These skin manifestations would persist for more than 24 hr and resolved with hyperpigmentation. The patient presented with marked swelling of the face and lip. Treatment with antihistaminic and prednisolone resulted in improvement of her skin lesions, and she thereafter received prednisolone intermittently depending on her symptom recurrence.

After 1 yr, she visited our hospital due to a malar rash and pitting edema of both the legs and recurrent episodes of urticaria (Fig. 1). She had not experienced dry eye or dry mouth. Laboratory tests revealed the following findings: hemoglobin level, 9.6 g/dL; white blood cell (WBC) count, 1,970/µL (neutrophils 62%); platelets, 269×103/µL; total protein, 6.3 g/dL; albumin, 2.7 g/dL; blood urea nitrogen (BUN), 14 mg/dL; creatinine, 1.0 mg/dL; and C-reactive protein, 1.4 mg/L. A high titer of antinuclear antibodies (ANA) was detected (1:640, speckled), while the test for double-stranded DNA antibody was negative. Anti-smith, anti-Ro, and anti-La antibodies were all positive.

The C3 level (28.7 mg/dL; normal range, 55-120 mg/dL), C4 level (6.3 mg/dL; normal range, 20-50 mg/dL), CH50 level (6.7 U/mL; normal range, 23-46 U/mL), and C1q level (6.6 mg/dL; normal range, 10-20 mg/dL) were markedly decreased, whereas the anti-C1q antibody level was increased to 23.3 U/mL (normal level, <10 U/mL). The C1 esterase inhibitor level was normal (25 mg/dL; normal range, 6-25 mg/dL) and cryoglobulin was not detected. The serological test results for hepatitis B and C viruses were negative. Urinary analysis showed protein, ++; red blood cell (RBC) count, 6-10/high-power field (HPF); and 24-hr urine protein, 1.1 g/day, and the creatinine clearance rate was 44.0 mL/min.

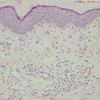

Skin biopsy revealed diffuse polymorphonuclear leukocyte infiltration in the dermis. In particular, distinct infiltration of neutrophils and nuclear dust was noted at the walls of small vessels (Fig. 2). Renal biopsy revealed subepithelial and mesangial immune deposits. IgG was positive along the capillary loop, and C1q and C3 were positive in the mesangium. Renal biopsy findings were compatible with membranous nephritis (Fig. 3).

The diagnosis of SLE was established because of the presence of a malar rash, proteinuria, leukopenia, high ANA titer, and the presence of the anti-smith antibody. The patient's skin lesion was diagnosed as hypocomplementemic urticarial vasculitis (HUV).

An intravenous steroid pulse (1.0 g/day×3 days) followed by a high-dose oral steroid (1 mg/kg) were administered after the disappearance of the vasculitic wheal and angioedema. Hematuria and proteinuria were resolved, and mycophenolate mofetil (500 mg, bid) and hydroxychloroquine were added to the therapy. However, in July 2007, the tapering of the steroid administration was accompanied by the recurrence of urticaria, angioedema, conjunctivitis, and episodes of abdominal pain. Despite mycophenolate mofetil, the patient's skin lesions recurred without recurrence of proteinuria. Treatment with prednisone and dapsone was initiated, and the urticaria resolved. Dapsone and steroid therapy did not completely relieve, but instead attenuated the urticarial vasculitic lesions.

Urticarial vasculitis resembles urticaria, is usually painful or nonpruritic, and typically persists for more than 24 hr (1). The lesion can sometimes be pruritic, but is more commonly asymptomatic or painful. It usually resolves with hyperpigmentation or purpura (1).

Patients with urticarial vasculitis can be divided into two groups, those with normal complement levels and those with HUV (1, 2). The latter are more likely to exhibit systemic manifestations, including constitutional symptoms (fever, malaise, and fatigue), arthralgia, arthritis, serositis, glomerulonephritis, interstitial nephritis, and Raynaud's phenomenon (2). Angioedema-like lesions are present in as many as 40% of patients, frequently involving the lips, tongue, periorbital tissue, and hands (2). Some patients have ocular inflammation like conjunctivitis and episcleritis (3).

By definition, serum complement levels are decreased in HUV. Complement measurements with low C1q and C4 levels and variably decreased C3 levels indicated activation of the classical pathway. C1q precipitins were identified and were later confirmed to be autoantibodies against C1q (anti-C1q autoantibody) (4). Antibodies against C1q act as a diagnostic marker for HUV (1, 3). However, they are not specific to HUV and have also been observed in SLE. Anti-C1q antibodies were detected in 30% of patients with SLE and 80% of SLE patients with glomerulonephritis (5). This patient also showed decreased levels of C3, C4, CH50, and C1q and increased levels of the anti-C1q antibody. She simultaneously exhibited HUV and SLE with glomerulonephritis, both of which are possible causes of decreased complement and the presence of anti-C1q antibody.

In most cases, the histological findings of urticarial vasculitis include a majority of features of completely developed leukocytoclastic vasculitis (2). Direct immunofluoroscence of skin biopsy samples from HUV patients usually show immunoglobulin and complement deposition in a granular pattern in and around the blood vessels of the upper dermis and the basement membrane (2).

This patient exhibited typical findings of HUV. She experienced recurrent urticaria with vasculitis, episodes of angioedema and eye inflammation, and the serum anti-C1q autoantibody was positive. She also fulfilled the criteria of SLE with urticarial lesions that persisted for more than 24 hr and left a brownish pigmentation, which is different from true urticaria.

The clinicopathologic features of HUV are similar to those of SLE. Some authors suggest the possible progression of HUV to SLE, and others have defined HUV as an SLE subtype (6, 7). At times, a hypocomplementemic patient initially diagnosed with an idiopathic HUV has an underlying disease such as SLE or Sjogren's syndrome (1). HUV is associated with SLE in most cases (54%), but normocomplementemic urticarial vasculitis is not strongly associated with SLE (2%) (8). This patient suffered from urticaria and angioedema for several years. Serum complement levels were not checked initially, and a skin biopsy was performed 1 yr after disease onset; the results revealed urticarial vasculitis. However, in this case, we assume that urticarial vasculitis was the presenting symptom of SLE.

HUV has been reported to be recurrent in some patients, with an unpredictable response to therapy (1, 2). Intravenous methylprednisolone and cyclophosphamide or high-dose oral corticosteroids, colchicines, dapsone, hydroxychloroquine, and low-dose methotrexate have all been reported to be effective treatments (1, 2, 9). In this patient, the skin lesions resolved initially with steroids, but were subsequently refractory to treatment. We increased the dose of steroid and added dapsone. Mycophenolate mofetil, which was administered for lupus nephritis, did not affect urticarial vasculitis.

In conclusion, if urticarial vasculitis is suspected, lesional skin should be biopsied. When histological findings suggest leukocytoclastic vasculitis, complement levels should be measured. Although HUV resembles SLE both clinically and immunologically, an association HUV and SLE is not clear yet.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 1Urticarial vasculitic skin lesions on the back of the patient. Urticarial plaques frequently persisted for more than 24 hr. |

References

3. Wisnieski JJ, Baer AN, Christensen J, Cupps TR, Flagg DN, Jones JV, Katzenstein PL, McFadden ER, McMillen JJ, Pick MA, Richmond GW, Simon SR, Smith HR, Sontheimer RD, Trigg LB, Weldon D, Zone JJ. Hypocomplementemic urticarial vasculitis syndrome: clinical and serologic findings in 18 patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 1995. 74:24–41.

4. Wisnieski JJ, Naff GB. Serum IgG antibodies to C1q in hypocomplementemic urticarial vasculitis syndrome. Arthritis Rheum. 1989. 32:1119–1127.

5. Siegert CE, Kazatchkine MD, Sjöholm A, Würzner R, Loos M, Daha MR. Autoantibodies against C1q: view on clinical relevance and pathogenic role. Clin Exp Immunol. 1999. 116:4–8.

6. Nishijima C, Hatta N, Inaoki M, Sakai H, Takehara K. Urticarial vasculitis in systemic lupus erythematosus: fair response to prednisolone/dapsone and persistent hypocomplementemia. Eur J Dermatol. 1999. 9:54–56.

7. Aydogan K, Karadogan SK, Adim SB, Tunali S. Hypocomplementemic urticarial vasculitis: a rare presentation of systemic lupus erythematosus. Int J Dermatol. 2006. 45:1057–1061.

8. Davis MD, Daoud MS, Kirby B, Gibson LE, Rogers RS 3rd. Clinicopathologic correlation of hypocomplementemic and normocomplementemic urticarial vasculitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998. 38:899–905.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download