Abstract

Complications associated with an intramural hematoma of the bowel, is a relatively unusual condition. Most intramural hematomas resolve spontaneously with conservative treatment and the patient prognosis is good. However, if the symptoms are not resolved or the condition persists, surgical intervention may be necessary. Here we describe internal incision and drainage by endoscopy for the treatment of an intramural hematoma of the duodenum. A 63-yr-old woman was admitted to the hospital with hematemesis. The esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) showed active ulcer bleeding at the distal portion of duodenal bulb. A total of 10 mL of 0.2% epinephrine and 2 mL of fibrin glue were injected locally. The patient developed diffuse abdominal pain and projectile vomiting three days after the endoscopic treatment. An abdominal computed tomography revealed a very large hematoma at the lateral duodenal wall, approximately 10×5 cm in diameter. Follow-up EGD was performed showing complete luminal obstruction at the second portion of the duodenum caused by an intramural hematoma. The patient's condition was not improved with conservative treatment. Therefore, 21 days after admission, endoscopic treatment of the hematoma was attempted. Puncture and incision were performed with an electrical needle knife. Two days after the procedure, the patient was tolerating a soft diet without complaints of abdominal pain or vomiting. The hematoma resolved completely on the follow-up studies.

Partial or complete bowel obstruction secondary to an intramural hematoma is a relatively unusual condition (1). Various etiological factors have been described in the medical literature. The most common factors include blunt trauma, anticoagulant therapy, Henoch-Schönlein purpura, and blood dyscrasias (1). An intramural hematoma is not a common complication of diagnostic or therapeutic endoscopy (1-8). Most intraluminal hematomas resolve spontaneously with conservative treatment and patients have a good prognosis. However, the abdominal pain or obstruction may not be resolved with conservative treatment and there may be evidence of infarction or peritonitis that require surgical intervention (9-11). We report endoscopic incision and drainage of an obstructive intramural hematoma of the duodenum that was not responsive to conservative management. The cause of this complication was the endoscopic treatment of a bleeding duodenal ulcer in a patient with diabetic nephropathy on hemodialysis. This is the first case report of this novel treatment in the English literature. Here we report the case with a review of the literature.

A 63-yr-old woman was admitted to the hospital with fresh bloody hematemesis, about 400 cc. The patient had a history of type 2 diabetes mellitus, essential hypertension and chronic hepatitis associated with hepatitis C virus (HCV). She was receiving hemodialysis for diabetic nephropathy three times a week. Four months prior to admission, she underwent esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD), which revealed a duodenal ulcer. The patient was started on 20 mg of a proton pump inhibitor (Rabeprazole) daily for 28 days. The patient denied taking non-steroidal anti-inflammatory, anti-platelet and anti-coagulation medications just before hospitalization. On physical examination, the temperature was 36.5℃, pulse rate was 100 beats per minute, and blood pressure was 140/80 mmHg. There was epigastric tenderness and pale conjunctivas. The relevant laboratory test results were as follows: hemoglobin 5.1 g/dL; leukocytes count 5,680/µL; platelet count 161,000/µL; prothrombin time 92%; partial thromboplastin time 34 sec; serum albumin 3.3 g/dL; total bilirubin 0.13 mg/dL; serum aspartate transaminase (AST) 29 U/L; and serum alanine transaminase (ALT) 33 U/L.

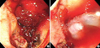

The EGD revealed multiple active ulcerations with large amounts of fresh blood clots and necrotic tissue materials at the distal portion of duodenal bulb (Fig. 1). A total of 10 mL of 0.2% epinephrine and 2 mL of fibrin glue were injected locally. The EGD also revealed the existence of multiple shallow gastric ulcers. After treatment with intravenous administration of a proton pump inhibitor and a transfusion with four pints of whole blood, the hemoglobin concentration level increased to 10.6 g/dL.

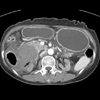

The patient developed severe abdominal pain over the entire abdomen three days after the endoscopic treatment. An emergency abdominal computed tomography (CT) revealed a huge hematoma at the lateral duodenal wall, approximately 10×5 cm in diameter (Fig. 2). Furthermore, the leukocyte count increased to 17,150/µL and the hemoglobin concentration decreased from 10.6 g/dL to 7.9 g/dL. In addition, the serum amylase level increased from 98 IU/L on admission to 5,103 IU/L. The patient was treated with intravenous administration of a proton pump inhibitor, continuous nasogastric suction and total parenteral nutrition. The serum amylase level decreased to 332 IU/L after four days and oral intake of liquid and food was started.

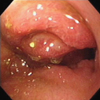

Thirteen days after admission, the patient developed hematemesis described as dark brown in color. The EGD revealed nearly complete obstruction of the lumen of the second portion of the duodenum by an intramural hematoma. The surface of the hematoma appeared to be covered with normal mucosa but was friable and red in color (Fig. 3). Sixteen days after admission, the patient developed fever (38.5℃). The leukocyte count increased to 21,950/µL and the serum amylase level increased to 530 IU/L. The follow-up abdominal CT series revealed an increase in the size of the intramural hematoma. The patient's symptoms did not improve with conservative management. Twenty-one days after admission, we attempted a novel treatment for the intramural hematoma using endoscopy instead of surgery.

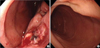

After the endoscope was inserted into the duodenum, we carefully punctured and incised the hematoma with an electrical needle knife. After the site was punctured, a large amount of a liquefied dark red colored material gushed out from the hematoma; the obstructed bowel lumen was unobstructed (Fig. 4). The follow-up EGD, seven days later, showed that the duodenal stenosis was partially improved and that the incision site was ulcerated (Fig. 5A). Further conservative treatment was followed by almost complete resolution of the duodenal stenosis and the entire hematoma. The ulcer was healed completely one month later (Fig. 5B).

Intramural hematomas, first recognized in 1838 (1), have been described in almost all areas of the gastrointestinal tract, ranging in position from the esophagus to the sigmoid colon; they are caused by a variety of etiologic factors. Many cases have been associated with blunt abdominal trauma, anticoagulant therapy, Henoch-Schönlein purpura, and blood dyscrasias (1).

An intramural hematoma is not a common complication of diagnostic or therapeutic endoscopy (1-8). Because of the fixed retroperitoneal location, and a rich submucosal blood supply, local injection or forceps biopsy can cause shearing of the mucosa from the fixed duodenal submucosa and induce the formation of an intramural hematoma (6-8). There are several therapeutic modalities for bleeding ulcers. However, the use of local injections of epinephrine, polidocanal and fibrin tissue adhesive onto the mucosa is the most common. Rohrer et al. (4), reported that the local injection of epinephrine followed by injection of polidocanol or fibrin tissue adhesive caused tissue damage, possibly leading to the development of intramural hematomas. It was therefore considered that local injection of fibrin tissue adhesive and relatively large amounts of 0.2% epinephrine solution might have caused this patient, with diabetic nephropathy on hemodialysis, to develop an intramural hematoma more easily.

Most patients with an intramural hematoma of the duodenum respond well to conservative treatment. The best conservative treatments are fluid and electrolyte replacement, nasogastric tube decompression and careful observation. If there is a history of anticoagulant medication, cessation of the anticoagulant and fresh-frozen plasma will often resolve the hyperprothrombinetic state. Vitamin K therapy should be instituted cautiously because overuse may precipitate a rebound hypercoagulable state (1, 11).

The development of abdominal pain, fever, leukocytosis, and hyperamylasemia after endoscopic intervention for duodenal ulcer bleeding suggested the presence of an acute pancreatitis due to the complications associated with the intramural hematoma of duodenum, which has a high mortality. Because of the negative blood cultures and relatively short period of fever, in this case, no secondary infection developed due to the bleeding. The presence of an intramural hematoma, with complications, should be treated as soon as possible to prevent morbidity and mortality.

The indications for surgical intervention for an intramural hematoma are not well established. Up to the early 1970s, most patients with a duodenal intramural hematoma were treated surgically, usually by careful incision and evacuation of the hematoma. A diverting gastrojejunostomy may be necessary if the duodenum is severely damaged and/or followed by bypass surgery (1). Beal et al. (9) recommended that surgical intervention might be necessary if the abdominal pain or obstruction did not resolve and the physical findings and laboratory data suggested an impending infarction. Jewett et al. (10) proposed that surgery should be reserved for those cases that remain obstructed over seven to ten days or have evidence of perforation. Polat et al. (11) suggested that surgery is indicated if generalized peritonitis or intestinal obstruction developed.

Several new therapeutic strategies have been reported since the early 1990s. Aizawa et al. (12) reported a patient with a duodenal hematoma treated with ultrasonically guided drainage and balloon dilatation. Maemura et al. (13) reported the usefulness of laparoscopic surgery for definitive treatment of an intramural duodenal hematoma caused by abdominal trauma. There are five prior reports of endoscopic incision used to treat spontaneous intramural dissection or hematoma of the esophagus (14-18).

This case illustrates that the novel treatment approach using endoscopic incision and drainage was simple, safe and effective for the treatment of obstruction caused by an intramural hematoma of the duodenum that was not responsive to conservative management. However, such intervention cannot be widely recommended based on a single case. Further study is needed to evaluate procedure related complications such as perforation and bleeding with prospective controlled trials to confirm the safety and efficacy of endoscopic treatment for an intramural hematoma.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Esophagogastroduodenoscopy on admission revealed multiple active ulcerations with large amounts of fresh blood clots and necrotic tissue materials at the distal portion of duodenal bulb (A). A total of 10 mL of 0.2% epinephrine and 2 mL of fibrin glue were injected locally (B).

Fig. 2

Contrast-enhanced abdominal CT scan findings on the 3rd hospital day. A very large hematoma at the lateral duodenal wall, approximately 10×5 cm in diameter was identified. In the hematoma, active bleeding from vessel was revealed (arrow).

Fig. 3

EGD on the 4th hospital day revealed severe stenosis of the second portion of the duodenum due to an intramural hematoma. The surface of the hematoma appeared to be covered with normal mucosa but was friable and red in color.

Fig. 4

EGD findings on the 21st hospital day. The hematoma was punctured and incised with an electrical needle knife (A). Soon after, a large amount of liquefied dark red colored material gushed out from the hematoma, and the obstructed bowel lumen was repaired (B).

Fig. 5

Follow-up EGD Findings. EGD Seven days after EGD showed that the duodenal stenosis was partially improved and the incision site was ulcerated (A). One month after EGD showed that the duodenal stenosis was almost completely resolved, and the entire hematoma collapsed. The ulcer was completely healed (B).

References

1. Hughes CE 3rd, Conn J Jr, Sherman JO. Intramural hematoma of the gastrointestinal tract. Am J Surg. 1977. 133:276–279.

2. Ghishan FK, Werner M, Vieira P, Kuttesch J, DeHaro R. Intramural duodenal hematoma: an unusual complication of endoscopic small bowel biopsy. Am J Gastroenterol. 1987. 82:368–370.

3. Zinelis SA, Hershenson LM, Ennis MF, Boller M, Ismail-Beigi F. Intramural duodenal hematoma following upper gastrointestinal endoscopic biopsy. Dig Dis Sci. 1989. 34:289–291.

4. Rohrer B, Schreiner J, Lehnert P, Waldner H, Heldwein W. Gastrointestinal intramural hematoma, a complication of endoscopic injection methods for bleeding peptic ulcers: a case series. Endoscopy. 1994. 26:617–621.

5. Lipson SA, Perr HA, Koerper MA, Ostroff JW, Snyder JD, Goldstein RB. Intramural duodenal hematoma after endoscopic biopsy in leukemic patients. Gastrointest Endosc. 1996. 44:620–623.

6. Guzman C, Bousvaros A, Buonomo C, Nurko S. Intraduodenal hematoma complicating intestinal biopsy: case reports and review of the literature. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998. 93:2547–2550.

7. Yen HH, Soon MS, Chen YY. Esophageal intramural hematoma: an unusual complication of endoscopic biopsy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005. 62:161–163.

8. Sugai K, Kajiwara E, Mochizuki Y, Noma E, Nakashima J, Uchimura K, Sadoshima S. Intramural duodenal hematoma after endoscopic therapy for a bleeding duodenal ulcer in a patient with liver cirrhosis. Intern Med. 2005. 44:954–957.

9. Beal JM, Haid S, Sherrick J, Scarff J, Rambach W, Method H. Small bowel obstruction secondary to hematoma of the mesentery. IMJ Ill Med J. 1966. 130:422–426.

10. Jewett TC Jr, Caldarola V, Karp MP, Allen JE, Cooney DR. Intramural hematoma of the duodenum. Arch Surg. 1988. 123:54–58.

11. Polat C, Dervisoglu A, Guven H, Kaya E, Malazgirt Z, Danaci M, Ozkan K. Anticoagulant-induced intramural intestinal hematoma. Am J Emerg Med. 2003. 21:208–211.

12. Aizawa K, Tokuyama H, Yonezawa T, Doi M, Matsuzono Y, Matumoto M, Uragami K, Nishioka S, Yataka I. A case report of traumatic intramural hematoma of the duodenum effectively treated with ultrasonically guided aspiration drainage and endoscopic balloon catheter dilation. Gastroenterol Jpn. 1991. 26:218–223.

13. Maemura T, Yamaguchi Y, Yukioka T, Matsuda H, Shimazaki S. Laparoscopic drainage of an intramural duodenal hematoma. J Gastroenterol. 1999. 34:119–122.

14. Murata N, Kuroda T, Fujino S, Murata M, Takagi S, Seki M. Submucosal dissection of the esophagus: a case report. Endoscopy. 1991. 23:95–97.

15. Bak YT, Kwon OS, Yeon JE, Kim JS, Byun KS, Kim JH, Kim JG, Lee CH, Choi YH, Kang DH. Endoscopic treatment in a case with extensive spontaneous intramural dissection of the oesophagus. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1998. 10:969–972.

16. Cho CM, Ha SS, Tak WY, Kweon YO, Kim SK, Choi YH, Chung JM. Endoscopic incision of a septum in a case of spontaneous intramural dissection of the esophagus. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2002. 35:387–390.

17. K C S, Kouzu T, Matsutani S, Hishikawa E, Saisho H. Early endoscopic treatment of intramural hematoma of the esophagus. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003. 58:297–301.

18. Adachi T, Togashi H, Watanabe H, Okumoto K, Hattori E, Takeda T, Terui Y, Aoki M, Ito J, Sugahara K, Saito K, Saito T, Kawata S. Endoscopic incision for esophageal intramural hematoma after injection sclerotherapy: case report. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003. 58:466–468.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download