1. Alexander SW, Walsh TJ, Frifeld AG, Pizzo PA. Pizzo PA, Poplack DG, editors. Infectious complications in pediatric cancer patients. Principles and practice of pediatric oncology. 2002. 4th ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Co;1239–1283.

2. Dickout WJ, Chan CK, Hyland RH, Hutcheon MA, Fraser IM, Morgan CD, Curtis JE, Messner HA. Prevention of acute pulmonary edema after bone marrow transplantation. Chest. 1987. 92:303–309.

3. Lee CK, Gingrich RD, Hohl RJ, Ajram KA. Engraftment syndrome in autologous bone marrow and peripheral stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1995. 16:175–182.

4. Maiolino A, Biasoli I, Lima J, Portugal AC, Pulcheri W, Nucci M. Engraftment syndrome following autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: definition of diagnostic criteria. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2003. 31:393–397.

5. Colby C, McAfee S, Sackstein R, Dey B, Saidman S, Sachs DH, Sukes M, Spifzer TR. Engraftment syndrome following nonmyeloablative conditioning therapy and HLA-matched bone marrow transplantation for hematologic malignancy. Blood. 2000. 96:520a.

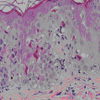

6. Canninga-van Dijk MR, Sanders CJ, Verdonck LF, Fijnheer R, van den Tweel JG. Differential diagnosis of skin lesions after allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Histopathology. 2003. 42:313–330.

7. Moreb JS, Kubilis PS, Mullins DL, Myers L, Youngblood M, Hutcheson C. Increased frequency of autoaggression syndrome associated with autologous stem cell transplantation in breast cancer patients. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1997. 19:101–106.

8. Sutkowi L, Pohlman B, Kalaycio B, Andresen S, Lichtin A, Goormastic M, McBee D, DeMars E, Kephart B. Clinical correlations of the engraftment syndrome. Blood. 1999. 94:146a.

9. Edenfield WJ, Moores LK, Goodwin G, Lee N. An engraftment syndrome in autologous stem cell transplantation related to mononuclear cell dose. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2000. 25:405–409.

10. Ravoet C, Feremans W, Husson B, Majois F, Kentos A, Lambermont M, Wallef G, Capel P, Beauduin M, Delannoy A. Clinical evidence for an engraftment syndrome associated with early and steep neutrophil recovery after autologous blood stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1996. 18:943–947.

11. Cahill RA, Spitzer TR, Mazumder A. Marrow engraftment and clinical manifestations of capillary leak syndrome. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1996. 18:177–184.

12. Moore MA. Review: Stratton Lecture 1990. Clinical implications of positive and negative hematopoietic stem cell regulators. Blood. 1991. 78:1–19.

13. Jadus MR, Wepsic HT. The role of cytokines in graft-versus-host reactions and disease. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1992. 10:1–14.

14. Takamatsu Y, Akashi K, Harada M, Teshima T, Inaba S, Shimoda K, Eto T, Shibuya T, Okamura S, Niho Y. Cytokine production by peripheral blood monocytes and T cells during haemopoietic recovery after intensive chemotherapy. Br J Haematol. 1993. 83:21–27.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download