Abstract

A 1D point-prevalence study was performed to describe the characteristics of conventional mechanical ventilation in intensive care units (ICUs). In addition, a survey was conducted to determine the characteristics of ICUs. A prospective, multicenter study was performed in ICUs at 24 university hospitals. The study population consisted of 223 patients who were receiving mechanical ventilation or had been weaned off mechanical ventilation within the past 24 hr. Common indications for the initiation of mechanical ventilation included acute respiratory failure (66%), acute exacerbation of chronic respiratory failure (15%) (including tuberculosis-destroyed lung [5%]), coma (13%), and neuromuscular disorders (6%). Mechanical ventilation was delivered via an endotracheal tube in 68% of the patients, tracheostomy in 28% and facial mask with noninvasive ventilation (NIV) in 4%. NIV was used in 2 centers. In patients who had undergone tracheostomy, the procedure had been performed 16.9±8.1 days after intubation. Intensivists treated 29% of the patients. A need for additional educational programs regarding clinical practice in the ICU was expressed by 62% of the staff and 42% of the nurses. Tuberculosis-destroyed lung is a common indication for mechanical ventilation in acute exacerbation of chronic respiratory failure, and noninvasive ventilation was used in a limited number of ICUs.

Advances in medicine have increased the use of mechanical ventilation in intensive care units (ICUs). Lung-protective ventilation has been credited with the recent decline in mortality from acute lung injury/acute respiratory distress syndrome (ALI/ARDS) (1-3).

Although some information exists on mechanical ventilation and related issues, limited data are available from Asian countries (4-6). The prevalence of specific diseases varies from country to country; for example, the prevalence of tuberculosis is higher in Asian countries. Because of these differences, the initiation of mechanical ventilation can vary from country to country.

Epidemiologic and environmental factors in the ICU are important to critical care because they can affect care and mortality. For example, the association between hospital volume and patient outcome has been clearly established for some medical and surgical units (7, 8). In addition, the availability of intensivists in the ICU can reduce mortality and improve patient outcome (9-12).

The aim of this study was to evaluate the indications for mechanical ventilation in the ICU, the characteristics of patients receiving mechanical ventilation, and the use of available ventilator modes, airway management, and weaning methods. The second aim of this study was to conduct a survey of ICU staff to determine the characteristics of ICUs.

A prospective multicenter study was conducted in Korea on March 25, 2003. The study was performed at 11:00 a.m. and involved 35 ICUs, including 18 medical ICUs, 8 medicosurgical ICUs, 4 surgical ICUs, 3 coronary care units, and 2 neurological ICUs. A private KOrean Study group on REspiratory Failure (KOSREF), consisting of ICU doctors, participated in the study. Most members of KOSREF worked in the pulmonary or anesthesia departments of tertiary or university-affiliated hospitals. Those who were interested in studying and researching critical care participated of their own accord. Pediatric ICUs and postoperative recovery areas were excluded. The study was approved by each hospital's institutional review board.

The study was confined to patients who were receiving mechanical ventilation, undergoing a spontaneous breathing trial, or who had been extubated within the 24 hr prior to 11:00 a.m. on the study date. Information on each hospital, each ICU, and the patients receiving ventilator support or weaning were collected on data sheets. Data sheets and physician questionnaires were mailed to KOSREF members before the study date.

The data collector recorded each patient's sex, age, predicted body weight (PBD), date of admission to the ICU, APACHE II score at the time of admission, date of mechanical ventilation initiation, and mode of airway access. If a patient had undergone a tracheostomy, the date of the procedure was noted.

Indications for the initiation of mechanical ventilation were selected from the following predefined categories, as derived from the literature (4, 6, 13): 1) Acute exacerbation of chronic respiratory failure (CRF) referred to obstructive or restrictive lung disease requiring mechanical ventilation because of infection, bronchospasm, heart failure, or an acute episode. Tuberculosis-destroyed lung (TDL) referred to destroyed lung parenchyma using pulmonary radiology and a history of present or past tuberculosis (13). 2) The term 'coma' was used in reference to patients who required mechanical ventilation owing to the loss of consciousness, secondary to organic or metabolic conditions. 3) Neuromuscular disease was used in reference to patients who required mechanical ventilation owing to impairment of the peripheral nerves, myoneural junction or muscle mass. 4) Acute respiratory failure was used in reference to patients without preexisting obstructive or restrictive lung disease who required mechanical ventilation because of respiratory failure. If a patient had multiple indications for mechanical ventilation, the attending staff indicated the dominant reason.

Patients with acute respiratory failure (ARF) were subdivided into groups, according to ARDS (1), postoperative state, acute pulmonary edema/congestive heart failure, aspiration, pneumonia, sepsis/septic shock (14), and trauma (4).

The data collector recorded the mechanical ventilation mode and settings at the time of the study. Weaning was defined on the basis of the attending staff's judgment and the method of weaning was recorded.

We developed a questionnaire to determine if ICUs are equipped with enough staff and medical instruments to properly care for patients. On the day of the study, each participating staff member in the ICU completed the questionnaire. The survey provided information about the ICU and the hospital, including the number of beds, the number of patients currently in the ICU, the number of patients receiving mechanical ventilation at the time, and the respective ratios of patients to staff, residents, and nurses. The survey also determined, the approximate number of patients of the department each participant worked in that the staff, residents, and nurses were caring for at the time of the study, whether an intensivist was included among the ICU staff, whether the participant thought the numbers of doctors and nurses were sufficient to care for the patients in the ICU, whether the participant thought ICR doctors and nurses needed additional educational programs on clinical practice, whether the participant had ever encountered a shortage of mechanical ventilators and patient monitors, whether the participant thought the medical instruments in the ICU were outdated, whether the ICU possessed an arterial blood gas analysis (ABG) machine, whether the ICU staff could check portable chest radiography within 10 min, and whether the surgeons cooperate immediately when they are asked to perform a tracheostomy or a tube thoracostomy.

Results were expressed as means±standard deviations. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 12.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, U.S.A.). One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) tests and post hoc multiple comparisons using Tukey's method were used to measure differences among the categories for initiation of mechanical ventilation. Differences were considered significant if the p value was less than 0.05.

The study comprised 619 ICU beds, which were occupied by 559 patients at the time of the study. This study included 223 patients (40%) who were receiving (177 patients) or had been weaned off (T-piece trial 22 patients, extubated 24 patients) mechanical ventilation at the time of the study. Characteristics of the patients and participating hospitals are summarized in Table 1.

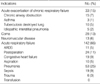

Among 216 patients studied, 66% received mechanical ventilation because of acute respiratory failure. These data did not include the seven patients who cited more than one reason for mechanical ventilation. Pneumonia was the most common indication of mechanical ventilation. An acute exacerbation of chronic respiratory failure was the precipitating cause of mechanical ventilation in 33 (15%) patients. COPD and TDL accounted for 7% and 5% of acute exacerbation of chronic respiratory failure, respectively (Table 2). In patients with CRF, age and APACHE II score were older and higher than those in patients with comas (Table 3).

Delivery of mechanical ventilation was performed using an endotracheal tube in 68% of patients, a tracheostomy in 28%, and a facial/nasal mask with noninvasive ventilation (NIV) in 4%. NIV was used in two centers. In patients receiving mechanical ventilation through endotracheal tubes, 128 (98%) were passed through the mouth and two (2%) through the nose. In patients who had undergone tracheostomy, the procedure had been performed an average of 16.9±8.1 days after intubation. The time between intubation and tracheostomy did not vary based on the underlying condition (Table 3).

In patients receiving mechanical ventilation, 51 (29%) received volume control ventilation (VCV) and 33 (19%) received pressure control ventilation (PCV). In 26 (15%), 33 (19%), and 25 (14%) patients, synchronized intermittent mandatory ventilation (SIMV), pressure support (PSV), or a combination of the two procedures were used, respectively. Nine patients (5%) received mechanical ventilation via other modes.

In patients receiving mechanical ventilation, the tidal volume was set to 8.1±2.1 mL/kg of the predicted body weight (PBW). Tidal volume varied according to underlying conditions (Table 3). The mean body weight was 58.6±9.6 kg. The mean positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) was 5.0±3.8 cm H2O and was employed in 78.6% of the ventilated patients. In those patients, a PEEP of 1-5 cm H2O was used in 39.2% of patients, while a PEEP of 6-10 cm H2O was used in 28.9% of patients and a PEEP greater than 10 cm H2O was used in 10.4% of patients. PEEP was higher in patients with acute respiratory failure than in patients with acute exacerbations of chronic respiratory failure (Table 3).

In all, 99 of 223 patients (44%), including 24 patients who were extubated within 24 hr, were in a weaning phase at the time of the study. Among the 75 patients undergoing weaning, PSV was used in 31 patients (41%) and T-piece trial was used in 22 (29%). A combination of SIMV and PSV was used in 11 (15%) patients, while SIMV was used in 6 (8%) and continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) was used in 5 (7%).

The survey response rate was 100%. The mean number of beds in the 24 participating hospitals was 866±399. The percentage of beds devoted to the ICU was 7±2%. The patient to staff ratio was 16.0±8.3, the patient to nurse ratio was 2.4±0.4, and the patient to resident ratio was 11.1±6.4. Most of the staff (79%) stated that the number of doctors working in the ICU was insufficient. Of the survey participants, 29% worked full-time in the ICU. A third of the ICU staff (32%) worked in the Department of Pulmonology, 18% worked in the Department of Anesthesiology and 50% worked in other departments.

Most of the staff (62%) and 42% of the nurses stated that they needed additional training in regard to clinical practice in the ICU. Most of the staff (83%) stated that there was a sufficient number of mechanical ventilators, and 79% of the staff felt that there was a sufficient number of patient monitors in the ICU. Seventy five percent of the staff stated that the medical instruments in the ICU were not out of date. An ABG machine was present in 33% of the ICUs. Fewer than half (42%) of the staff stated that they could check portable chest radiography within 10 min. Likewise, fewer than half (46%) felt that the ICU surgeons cooperated immediately when they were asked to do tracheostomy or a tube thoracostomy.

In this 1-D point-prevalence multicenter study of ICUs, pneumonia was the most common indication of mechanical ventilation, and COPD and TDL were common causes of acute exacerbation of chronic respiratory failure. Nasotracheal intubation and NIV were seldom used and tracheostomy after intubation was often performed late period. In addition, the survey suggested that additional personnel and training programs are needed to supplement the knowledge of ICU caregivers.

Among the patients with acute respiratory failure, the proportion of ARDS was similar in comparison to other reports (15, 16). However, pneumonia ccounted for 37% of the ventilated patients in this study. This is high proportion of patients, compared with 13% of pneumonia cases reported in the U.S.A. and 18% reported in Spain (4). It is possible that heavy consumption of cigarettes and alcohol in Korea contributes to the high occurrence of pneumonia. However, this study did not examine patient histories for evidence of alcohol and tobacco use. Among the subgroups of acute exacerbations of chronic respiratory failure, it is noteworthy that TDL was one of the common reasons for receiving mechanical ventilation. The prevalence of tuberculosis in Korea is 0.5%, which is higher than the prevalence in Westernized countries, while the mortality from tuberculosis is 6.6 people per 100,000. Therefore, TDL should be considered an important reason for mechanical ventilation in patients with CRF in an area with a high prevalence of tuberculosis.

Previous studies have found that the incidence of tracheostomy varies according to patients' underlying medical conditions (4-6). The results of our study do not support this observation. While underlying conditions or APACHE scores were similar to previous reports (4), the mean time before tracheostomy (16.9 days) was longer than that observed in North America (12 days) and Spain (11 days) (17). Furthermore, nasotracheal intubation was used in only 1% of cases, whereas this procedure is used in 5% of cases in North America and in 16% of cases in Portugal (4). We hypothesize that cultural differences could contribute to the delay in tracheostomies in Korea, which would explain why no differences were observed in the incidence of tracheostomies relative to the underlying medical conditions. Further studies of airway management and outcomes in Korean ICUs are needed.

Only two centers (4% of the mechanical ventilation mode) used NIV in this study, possibly because NIV requires trained physicians, nurses, respiratory therapists, and specific equipment. Utilization of NIV varied among hospitals, suggesting that more education on the utility and methodology of NIV is needed (18).

Although the results of this study showed that VCV was the most commonly used mode in the ICU, the use of pressure modes (PCV or PSV) was similar to the use of volume modes (VCV or SIMV). Ventilator modes were applied differently by each center (data not shown) and the use of several new ventilator modes seems limited. Future studies should follow up on these results.

The tidal volume in the ventilated patients was 8.1±2.1 mL/kg of PBW. Baseline characteristics appeared to vary according to disease groups, and ICU doctors applied different tidal volumes and PEEP according to disease groups. This suggests that physicians are aware of ventilator-induced lung injury and are making an effort to adjust the PEEP levels depending on the cause of respiratory failure.

In terms of manpower, there were both quantitative and qualitative problems involved in caring for ICU patients. Previous studies have shown that the presence of intensivists reduces mortality and improves outcome in ICUs (9-12). However, only 29% of patients in this study were treated by intensivists. About half of the ICU caregivers desired further training in regard to caring for ICU patients. The study also detected qualitative problems, such as a lack of cooperation from surgeons, limited access to portable chest radiography machines, and limited access to ABG machines in the ICU. However, the availability of instruments such as ventilators and monitors did not appear to interfere with the ability of ICU staff to care for patients.

A potential limitation of this study was that the ICUs were not selected randomly. Identification of the ICUs and their voluntary participation may have introduced a selection bias, as it cannot be assumed that the participating ICUs are entirely representative of Korean medical centers. However, our study included large, university-affiliated hospitals from different provinces in an attempt to obtain an accurate representation. Furthermore, because only a few SICU were examined, postoperative patients made up 11% of the total study population. The questions in this survey were general, so further research is needed to address specific questions and thereby improve the quality of critical care. Finally, the authors were unable to visit each medical center and relied upon the ICU staff members to provide accurate feedback.

In conclusion, the results of this study suggest that TDL is a common indication for mechanical ventilation in acute exacerbation of chronic respiratory failure, that further studies are needed to address current problems in airway management, and that ICU doctors and nurses desire more staff and additional training in the field of critical care medicine.

Figures and Tables

Table 3

Characteristics of patients and ventilator settings, according to the indication for mechanical ventilation

Data are expressed in mean±standard deviation.

*,Days from intubation to tracheostomy; †,p<0.05 compared with the coma group; ‡,p<0.05 compared with the ARF group.

MV, mechanical ventilation; CRF, acute exacerbation of chronic respiratory failure; ARF, acute respiratory failure; PBW, predicted body weight; PEEP, positive end-expiratory pressure.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

Participants are listed. Hyuk Pyo Lee (Sanggye Paik Hospital); Young-Joo Lee (Ajou University Hospital); Jung Bock Hyun (Gangneung Asan Hospital); Lim Sung Chul (Chonnam National University Hospital); Ahn Jong-Joon (Ulsan University Hospital); Jung Hyun Chang (Mokdong Hospital); Jeong Woong Park (Gil Medical Center); Kang-Hyeon Choe (Chungbuk National University Hospital); Yun Seong Kim (Pusan National University Hospital); Shin OK Koh (Shinchon Severance Hospital); Jae Hwa Cho (Inha University Hospital); Younsuck Koh, Chae-Man Lim (Asan Medical Center); Jae Ho Lee (Bungdang Seoul National University Hospital), Oh Jung Kwon (Samsung Medical Center); Kwang Seok Eom, Myung-Goo Lee, Ki-Suck Jung (Hallym University Sacred Heart Hospital).

References

1. Bernard GR, Artigas A, Brigham KL, Carlet J, Falke K, Hudson L, Lamy M, Legall JR, Morris A, Spragg R. The American-European Consensus Conference on ARDS. Definitions, mechanisms, relevant outcomes, and clinical trial coordination. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994. 149:818–824.

2. Amato MB, Barbas CS, Medeiros DM, Magaldi RB, Schettino GP, Lorenzi-Filho G, Kairalla RA, Deheinzelin D, Munoz C, Oliveira R, Takagaki TY, Carvalho CR. Effect of a protective-ventilation strategy on mortality in the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1998. 338:347–354.

3. The Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Network. Ventilation with lower tidal volumes as compared with traditional tidal volumes for acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome. The Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Network. N Engl J Med. 2000. 342:1301–1308.

4. Esteban A, Anzueto A, Alia I, Gordo F, Apezteguia C, Palizas F, Cide D, Goldwaser R, Soto L, Bugedo G, Rodrigo C, Pimentel J, Raimondi G, Tobin MJ. How is mechanical ventilation employed in the intensive care unit? An international utilization review. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000. 161:1450–1458.

5. Luhr OR, Antonsen K, Karlsson M, Aardal S, Thorsteinsson A, Frostell CG, Bonde J. Incidence and mortality after acute respiratory failure and acute respiratory distress syndrome in Sweden, Denmark, and Iceland. The ARF Study Group. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999. 159:1849–1861.

6. Esteban A, Alia I, Ibanez J, Benito S, Tobin MJ. Modes of mechanical ventilation and weaning. A national survey of Spanish hospitals. The Spanish Lung Failure Collaborative Group. Chest. 1994. 106:1188–1193.

7. Halm EA, Lee C, Chassin MR. Is volume related to outcome in health care? A systematic review and methodologic critique of the literature. Ann Intern Med. 2002. 137:511–520.

8. Kahn JM, Goss CH, Heagerty PJ, Kramer AA, O'Brien CR, Rubenfeld GD. Hospital volume and the outcomes of mechanical ventilation. N Engl J Med. 2006. 355:41–50.

9. Varelas PN, Conti MM, Spanaki MV, Potts E, Bradford D, Sunstrom C, Fedder W, Hacein Bey L, Jaradeh S, Gennarelli TA. The impact of a neurointensivist-led team on a semiclosed neurosciences intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2004. 32:2191–2198.

10. Pronovost PJ, Jenckes MW, Dorman T, Garrett E, Breslow MJ, Rosenfeld BA, Lipsett PA, Bass E. Organizational characteristics of intensive care units related to outcomes of abdominal aortic surgery. JAMA. 1999. 281:1310–1317.

11. Young MP, Birkmeyer JD. Potential reduction in mortality rates using an intensivist model to manage intensive care units. Eff Clin Pract. 2000. 3:284–289.

12. Pollack MM, Katz RW, Ruttimann UE, Getson PR. Improving the outcome and efficiency of intensive care: the impact of an intensivist. Crit Care Med. 1988. 16:11–17.

13. Park JH, Na JO, Kim EK, Lim CM, Shim TS, Lee SD, Kim WS, Kim DS, Kim WD, Koh Y. The prognosis of respiratory failure in patients with tuberculosis destroyed lung. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2001. 5:963–967.

14. Bone RC, Balk RA, Cerra FB, Dellinger RP, Fein AM, Knaus WA, Schein RM, Sibbald WJ. Definitions for sepsis and organ failure and guidelines for the use of innovative therapies in sepsis. The ACCP/SCCM Consensus Conference Committee. American College of Chest Physicians/Society of Critical Care Medicine. Chest. 1992. 101:1644–1655.

15. Knaus WA, Sun X, Hakim RB, Wagner DP. Evaluation of definitions for adult respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994. 150:311–317.

16. Ferring M, Vincent JL. Is outcome from ARDS related to the severity of respiratory failure? Eur Respir J. 1997. 10:1297–1300.

17. Griffiths J, Barber VS, Morgan L, Young JD. Systematic review and meta-analysis of studies of the timing of tracheostomy in adult patients undergoing artificial ventilation. BMJ. 2005. 330:1243.

18. Carlucci A, Richard JC, Wysocki M, Lepage E, Brochard L. Noninvasive versus conventional mechanical ventilation. An epidemiologic survey. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001. 163:874–880.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download