Abstract

Albendazole binds to parasite's tubulin inhibiting its glucose absorption. Its common adverse effects are nausea, vomiting, constipation, thirst, dizziness, headache, hair loss and pruritus. Although mainly metabolized in the liver, abnormal liver function tests were a rare adverse effect during clinical trials and we found no literature about albendazole-induced hepatitis requiring admission. This patient had a previous history of albendazole ingestion in 2002 resulting in increase of liver function tests. And in 2005, the episode repeated. We evaluated the patient for viral hepatitis, alcoholic liver disease, and autoimmune hepatitis, but no other cause of hepatic injury could be found. Liver biopsy showed periportal steatosis and periportal necrosis. The initial abnormal liver function test improved only with supportive care. These findings and the Roussel Uclaf Causality Assessment Method of the Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences (RUCAM/CIOMS) score of 9 are compatible with drug-induced hepatitis so we report the case of this patient with a review of the literature.

Albendazole (Su Do Albendazole 400 mg®, Su Do Pharm, Ind. Seoul, Korea) binds to parasite's tubulin inhibiting its glucose absorption. Its common adverse effects are nausea, vomiting, constipation, thirst, dizziness, headache, hair loss and pruritus (1). Although mainly metabolized in the liver, abnormal liver function test is known to be a rare adverse effect, and after prolonged administration, a mild increase of the liver function tests has been reported. But we found no previous reports about drug-induced hepatitis caused by albendazole requiring admission.

We experienced a case with a marked increase of aminotransferase levels due to albendazole ingestion. So we report this case with a review of the literature.

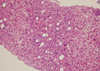

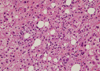

A 47-yr-old male patient came to our emergency center due to fever, chill, myalgia, nausea, vomiting and skin rash on both forearms for 6 hr after antiparasitic drug ingestion 2 days before. He received medication for common cold at local clinic for 2 days but showed no improvement of the symptoms. There was no history of specific medication. He was a social alcohol drinker and had a previous history of admission due to unknown origin hepatitis 3 yr before at our hospital, which the patient correlated with albendazole ingestion. The initial vital signs were blood pressure 150/70 mmHg, heart rate 72/min, respiratory rate 20/min and body temperature 38.3℃. He had no recent history compatible with acute hypotension or having underlying heart disease. In the physical examination liver was not palpable, liver percussion span was normal and there was no remarkable finding except icteric sclerae. In laboratorial analysis WBC was 6,790/µL (eosinophil 8.2%), hemoglobin 15.7 g/dL, and platelet 147,000/µL showing mild increase of eosinophil count. Prothrombin time 17.4 sec (INR 1.44), AST 5,402 IU/L, ALT 4,622 IU/L, alkaline phosphatase 40 IU/L, total bilirubin 2.8 mg/dL, r-GTP 101 IU/L, LDH 8,799 IU/L, total protein 6.9 g/dL, albumin 4.0 g/dL, serum glucose 115 mg/dL, and BUN/Cr, 19/1.1 mg/dL. IgM anti-HAV, HBsAg, IgM anti-HBc and anti-HCV Antibodies were negatives. Anti-CMV, anti-EBV, and anti-HSV were also negatives. Antinuclear antibody was weakly positive with homogeneous pattern and anti-mitochondrial antibody, anti-smooth muscle antibody were negative. The level of copper (urine) was 48.40 g/day, ceruloplasmin 26.1 mg/dL, IgG 1,313.2 mg/dL, and IgM 56.2 mg/dL showing normal values. Liver sonography showed no significant abnormality except increased liver echogenicity. Sonography-guided liver biopsy showed periportal invasion of inflammatory cells, cytotoxic necrosis and different sizes of steatosis (Fig. 1, 2). We suspected drug-induced hepatitis due to albendazole. And after a new interrogation of his past medical history, we knew that he had a previous history of albendazole ingestion before hospital admission due to unknown origin toxic hepatitis 3 yr previously. We diagnosed the patient as toxic acute hepatitis due to the Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences (CIOMS) score of 9 and performed conservative medical treatment. The patient showed rapid improvement of liver function test with AST 35 IU/L, ALT 301 IU/L, alkaline phosphatase 45 IU/L and total bilirubin 0.8 mg/dL on 8th day of admission. The patient was discharged and on follow-up at the outpatient department without significant symptoms.

Drug-induced liver injuries are reported with differences depending of methods of analysis and diagnosis, ranging from 1 of 600 to 3,500 of all admitted patients, and 2 to 3% of patients admitted due to drug-induced toxicity (2). Also even some approved drugs cause hepatitis by particular reactions with a frequency of 1 from 100,000 (3). In present days there is an unfounded belief that alternative medicine should cause less damage than usual medications, leading to its abuse (4). Also in the case of antiparasitic drugs the general population frequently ingests them for prophylactic purposes. Druginduced hepatitis is defined as hepatitis caused by some medication with or without prescription. Toxic hepatitits also includes traditional, alternative or natural medications (5). Usually toxic and drug-induced hepatitis are classified in direct toxic agents and idiosyncratic agents. Direct toxic agents are those which liver injury can be predicted by its use, has a dose-dependant nature and in most cases the time between exposure and latent period is short. With the use of idiosyncratic agents liver injury usually cannot be predicted and it is not dose-dependant. But extrahepatic hypersensitivity symptoms like skin eruptions, arthralgia, fever, leukocytosis and eosinophilia appear (2). In clinical trials, treatment with albendazole has been associated with mild to moderate elevations of hepatic enzymes in approximately 16% of patients. Although generally returned to normal upon discontinuation of therapy, there have been case reports of hepatitis (5). In the case of our patient the diagnosis of drug-induced hepatitis could be established due to the history of antiparasitic agent ingestion, fever, eosinophilia, and development of the symptoms within 12 hr since the ingestion moment.

Liver injuries are classified in 3 types: hepatocellular injury, cholestatic and combined (6). In the present case ALT was increased to 4,622 IU/L and ALP within normal limit being classified as hepatocellular injury type.

For the diagnosis of toxic hepatitis there are not absolute criteria or specific diagnosis methods. So scales with diagnostic points are utilized. The most commonly used is the semi-qualitative Roussel Uclaf Causality Assessment Method of the Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences (RUCAM/CIOMS) scale, which correlates a causing agent and toxic liver injury and the possible results are: 'highly probable', 'probable', 'possible', 'unlikely' or 'excluded' based on the total score obtained (7, 8).

In this case, a rechallenge test with albendazole was not performed because of the potential risk of severe liver injury. Nevertheless, as symptoms appeared 6 hr after albendazole administration, the time course and the absence of other probable causes of acute liver damage both are suggestive of a causative role for this drug. Also the local medication for common cold was administered after the symptoms began and even considering its possibility, a RUCAM/CIOMS score 9 was applied which indicated that a diagnosis of albendazole induced liver injury was "highly probable". Also clinical feature and laboratorial analysis improved rapidly during the past and present admission only with conservative manages. Hepatitis A, B, and C were negatives with serum analysis and sonography-guided liver biopsy excluded the possibilities of autoimmune and biliary hepatitis, showing features of acute hepatocellular hepatitis. Also hemoglobinopathy or Wilson's disease were excluded. The past history of the patient with previous ingestion of antiparasitic drug, the same symptoms (fever, myalgia, and right upper abdominal pain) and the laboratorial analysis values were similar. The possibility of immunologic liver injury could be considered because of fever, eosinophilia, liver biopsy and the development of the symptoms within 12 hr since the ingestion of the drug.

Previously Morris and Smith have reported abnormalities of liver function tests in seven patients during treatment of 40 patients for Echinococcus granulosus with oral albendazole. Six of these patients had the hepatocellular type of abnormality and one developed an obstructive jaundice (9). Jagota also reported a case of jaundice due to albendazole in a patient with hydatid disease of the liver, who was confirmed in a rechallenge with recurrence of hepatitis (10). In a letter by the same author recommends an albendazole dose of 400 mg twice daily, taken with meals, for a total of 28 days. Three such 28 days cycles may be given at 14 days intervals (11). The actual recommended dose of albendazole for hydatid disease patients with less than 60 kg by GlaxoSmithKline is 15 mg/kg/day (5).

Limitations in our case are the lack of exact medical record about antiparasitic drug ingestion 3 yr before, so we had to depend on the patient's memory. But, based on the previously mentioned criteria we think that the diagnosis of albendazole-induced hepatitis could be established.

We found literatures about the possible trial of steroids in drug induced hepatitis patients with allergic symptoms. Also in cholestatic drug induced hepatitis, ursodiol could be of use (12, 13). Our patient presented with symptoms of allergic reactions such as mild eosinophilia and skin rash, but improved rapidly only with conservative manages. Also in patients with history of previous liver disease, including hepatic echinococcosis, appear to be more susceptible to bone marrow suppression leading to pancytopenia, aplastic anemia, agranulocytosis, and leucopenia, but our patient did not present those signs. Albendazole should not be used in pregnant women except in clinical circumstances where no alternative management is appropriate (5). Long-term carcinogenicity and infertility studies in mice and rats showed no evidence of their increased incidence but albendazole has shown to be teratogenic in pregnant rats and rabbits (Pregnancy Category C) (5).

It's frequent that the general population ingests antiparasitic drugs every year for prophylactic purposes which can be bought without prescription and exact knowledge about the drug. As presented in our case albendazole can cause severe liver injury, so physicians must have in mind its possibilities despite of its rareness. The use of these easily accessible antiparasitic drugs for prophylactic purposes must be contraindicated and must be consulted with a physician about its indication. Based on this case we conclude that during the history taking of a hepatitis patient the possible ingestion of antiparasitic drug must be asked and further studies and reports about albendazole induced liver injuries are required.

Figures and Tables

References

1. Albendazole. 2000. MICROMEDEX;Available at:

http://www.micromedex.com

.

2. Kwak SJ, Oh HY, Yeo MA, Park SH, Kim JS, Lee JS, Kim HG. Fluoxetine-induced acute toxic hepatitis. Korean J Hepatol. 2000. 6:236–240.

3. Chae HB. Clinical features and diagnosis of drug-induced liver injury. Korean J Hepatol. 2004. 10:7–18.

4. Son HS, Kim GS, Lee SW, Kang SB, Back JT, Nam SW, Lee DS, Ahn BM. Toxic hepatitis associated with carp juice ingestion. Korean J Hepatol. 2006. 12:103–106.

5. Albenza® (albendazole) Tablets. Prescribing Information. 2007. Glaxo-SmithKline.

6. Seo JC, Jeon WJ, Park SS, Kim SH, Lee KM, Chae HB, Park SM, Youn SJ. Clinical experience of 48 acute toxic hepatitis patients. Korean J Hepatol. 2006. 12:74–81.

7. Benichou C. Criteria of drug-induced liver disorders. Report of an international consensus meeting. J Hepatol. 1990. 11:272–276.

8. Danan G, Benichou C. Causality assessment of adverse reactions to drugs--I. A novel method based on the conclusions of international consensus meetings: application to drug-induced liver injuries. J Clin Epidemiol. 1993. 46:1323–1330.

9. Morris DL, Smith PG. Albendazole in hydatid disease-hepatocellular toxicity. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1987. 81:343–344.

10. Jagota SC. Jaundice due to albendazole. Indian J Gastroenterol. 1989. 8:58.

11. Choudhuri G, Prasad RN. Jaundice due to albendazole. Indian J Gastroenterol. 1988. 7:245–246.

12. Ahn BM. Acute toxic hepatitis: RUCAM application to drug-induced liver injury and its limitations. Korean J Hepatol. 2006. 12:1–4.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download