Abstract

The exact pathogenesis of transient mid- and basal ventricular ballooning, a new variant of transient left ventricular (LV) ballooning, remains unknown. We report two cases of transient mid- and basal ventricular ballooning associated with catecholamines. These cases suggest that catecholamine-mediated myocardial dysfunction might be a potential mechanism of this syndrome.

Transient mid- and basal ventricular ballooning is a new variant of transient left ventricular (LV) ballooning similar to transient LV apical ballooning syndrome, mainly due to emotional and physical stress (1-4). Its exact mechanism of pathogenesis remains unknown. We report transient mid- and basal ventricular ballooning associated with catecholamines in two patients. These cases showed similar clinical courses to transient LV apical ballooning syndrome and catecholamine-mediated myocardial dysfunction, which might be a potential mechanism of this syndrome.

A 32-yr-old man presented to our emergency department with palpitation and squeezing chest pain. His initial blood pressure was 190/112 mmHg and electrocardiogram showed sinus tachycardia of 120/min. The initial electrocardiogram showed slight ST segment elevation in the inferior leads (lead II, III, and aVF). Echocardiography demonstrated a dilated mid portion of the LV and LV ejection fraction was 35% (Fig. 1A, B). However, the motion of the LV apex was normal. During the echocardiographic examination, his heart rate decreased suddenly to 70/min from 122/min. Serum level of creatinine kinase (CK) was 177 IU/L (normal range: 55-170 IU/L), CK-MB was 7.8 ng/mL (normal range: 0-4 ng/mL), and troponin I was 1.74 ng/mL (normal range: 0-0.05 ng/mL). The serum level of N-terminal-pro-B type natriuretic peptide (NT-pro-BNP) was increased up to 733 pg/mL (normal range: <200 pg/mL).

We performed emergent cardiac catheterization to rule out acute myocardial infarction. The coronary arteries were free of any organic stenosis and LV showed severe hypokinesia in the mid to basal portion. However, the LV apical wall motion was preserved (Fig. 2).

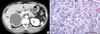

To rule out pheochromocytoma, we performed abdominal computerized tomography (CT). An abdominal CT showed an approximately 7.8×8.3×10.0 cm large septated cystic mass with irregular wall enhancement of the right adrenal gland (Fig. 3A). His serum catecholamine levels were reported as follows: epinephrine, 436.1 pg/mL (normal range: 0-140 pg/mL) and norepinephrine, 509.7 pg/mL (normal range: 0-450 pg/mL). The urinary catecholamine levels were as follows: epinephrine, 1,530.6 µg/day (normal range: 10-20 µg/day), norepinephrine, 1,048.8 µg/day (normal range: 15-80 µg/day) and metanephrine, 22,107.4 µg/day (normal range: 52-341 µg/day). From these findings, catecholamine induced cardiomyopathy showing midventricular ballooning was our final diagnosis.

The patient was treated with oral furosemide, an oral alpha blocker (prazosin) and intravenous nitrate infusion. The low dose of beta blocker was initiated after alpha blockade. The follow up echocardiography after three days of treatment showed marked improvement of LV systolic function and decreased LV dimension. The LV ejection fraction was 59%, with no regional wall motion abnormalities (Fig. 1C, D). He underwent successful surgical resection and the pathologic findings of the excised adrenal gland were compatible with pheochromocytoma (Fig. 3B).

A 47-yr-old man with no cardiac history presented with hypotension after resection of an inverted papilloma of the left nasal cavity. He was treated with subcutaneous epinephrine (epinephrine HCl 1 mg/ample) injection, about 0.2-0.3 mL, to the nasal mucosa to prevent excessive bleeding. After the injection, his systolic blood pressure and heart rate transiently increased to 170 mmHg and 140/min, respectively, then decreased to 50 mmHg and 70/min, respectively. Electrocardiogram showed normal sinus rhythm and no significant change of his initial electrocardiogram.

Echocardiography demonstrated a dilated LV, akinesia of the basal to mid portion of the LV with sparing of apex and LV ejection fraction was 28% (Fig. 4A, B). Serum level of CK was 248 IU/L (normal range: 55-170 IU/L), CK-MB was 9.1 ng/mL (normal range: 0-4 ng/mL), and troponin I was 5.4 ng/mL (normal range: 0-0.05 ng/mL). The serum level of NT-pro-BNP was increased up to 4,277 pg/mL (normal range: <200 pg/mL). No coronary angiography was performed because of the low probability of coronary arterial disease and a normal preoperative treadmill exercise test. A follow-up echocardiogram obtained after two days of conservative treatment showed normalized LV size and function (Fig. 4C, D). The LV ejection fraction was 56%, with no regional wall motion abnormalities. Treatment with β-blocker and angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor was initiated and continued for about one month after normalization of LV function.

We report two cases of transient mid- and basal ventricular ballooning syndrome associated with catecholamines. Transient mid- and basal ventricular ballooning is a new variant of the transient LV apical ballooning syndrome, which is also known as "stress cardiomyopathy", and includes transient cardiac contractile abnormalities and heart failure precipitated by acute emotional or physical stress. However, the involvement of the LV's mid- and basal ventricle with sparing of the apical segment is the unique finding of this variant (1, 2). Proposed potential mechanisms of transient LV apical ballooning are multivessel epicardial spasm, microvascular dysfunction of the coronary arteries, impaired fatty acid metabolism, myocarditis and catecholamine-mediated myocardial dysfunction (1, 3, 5). Although the mechanism underlying the association between sympathetic stimulation and myocardial stunning is unknown, several proposed mechanisms have been proposed including coronary arterial spasm (6) and direct injury to myocytes (7). Moreover, transient LV apical ballooning can be observed in patients with excessive circulating catecholamines with pheochromocytoma (8). Although there was a case report of apical ballooning associated with pheochromocytoma, our report seems to be the first to demonstrate that mid- and basal ventricular ballooning is related with high blood catecholamines (8).

The reason for apical ballooning with sparing of the basal segment is unknown. One possible explanation is different distribution of sympathetic nerves (9) and dissimilar density of sympathetic nerves in the heart (10), which make the apex more vulnerable to a sudden increase in circulating catecholamine levels. In our cases, the patients showed severe mid- and basal ventricular dysfunction from transient elevation of blood catecholamine level probably due to hemorrhagic necrosis of the adrenal pheochromocytoma and injection of epinephrine, respectively. The variations in segmental involvement regardless of coronary anatomy in patients with excessive catecholamine levels may suggest different susceptibility to sympathetic stimulation from individual to individual.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 1An apical four-chamber view of the left ventricle in the emergency department is shown at end-diastole (A) and end-systole (B). At end-systole, mid- and basal ventricular ballooning was noted. The follow-up echocardiographic study was performed after three days of treatment. The left ventricular dimension was decreased and ballooning had disappeared (C at end-diastole and D at end-systole). |

| Fig. 2The coronary angiogram showed normal left (A) and right coronary arteries (B). The left ventriculogram in the right anterior oblique view showed at end-diastole (C) and end-systole (D). At end-systole, mid- and basal ventricular ballooning was noted. However, LV apical motion was normal. |

| Fig. 3

(A) Abdominal computerized tomography showed an approximately 7.8×8.3×10.0 cm sized large septated cystic mass with irregular wall enhancement of the right adrenal gland (arrow). (B) Large and pink cells are arranged in nests with capillaries between them in the high power field image, which is compatible with pheochromocytoma. |

| Fig. 4An apical four-chamber view of the left ventricle after operation is shown at end-diastole (A) and end-systole (B). At end-systole, the mid-and basal ventricular ballooning was noted with sparing of the LV apex. A follow-up echocardiographic study was performed after two days. The left ventricular dimension had decreased and ballooning was no longer present (C at end-diastole and D at end-systole). |

References

1. Hurst RT, Askew JW, Reuss CS, Lee RW, Sweeney JP, Fortuin FD, Oh JK, Tajik AJ. Transient midventricular ballooning syndrome: a new variant. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006. 48:579–583.

2. Yasu T, Tone K, Kubo N, Saito M. Transient mid-ventricular ballooning cardiomyopathy: a new entity of Takotsubo cardiomyopathy. Int J Cardiol. 2006. 110:100–101.

3. Tsuchihashi K, Ueshima K, Uchida T, Oh-mura N, Kimura K, Owa M, Yoshiyama M, Miyazaki S, Haze K, Ogawa H, Honda T, Hase M, Kai R, Morii I. Angina Pectoris-Myocardial Infarction Investigations in Japan. Transient left ventricular apical ballooning without coronary artery stenosis: a novel heart syndrome mimicking acute myocardial infarction. Angina Pectoris-Myocardial Infarction Investigations in Japan. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001. 38:11–18.

4. Park JH, Kang SJ, Song JK, Kim HK, Lim CM, Kang DH, Koh Y. Left ventricular apical ballooning due to severe physical stress in patients admitted to the medical ICU. Chest. 2005. 128:296–302.

5. Wittstein IS, Thiemann DR, Lima JA, Baughman KL, Schulman SP, Gerstenblith G, Wu KC, Rade JJ, Bivalacqua TJ, Champion HC. Neurohumoral features of myocardial stunning due to sudden emotional stress. N Engl J Med. 2005. 352:539–548.

6. Lacy CR, Contrada RJ, Robbins ML, Tannenbaum AK, Moreyra AE, Chelton S, Kostis JB. Coronary vasoconstriction induced by mental stress (simulated public speaking). Am J Cardiol. 1995. 75:503–505.

7. Bolli R, Marban E. Molecular and cellular mechanisms of myocardial stunning. Physiol Rev. 1999. 79:609–634.

8. Takizawa M, Kobayakawa N, Uozumi H, Yonemura S, Kodama T, Fukusima K, Takeuchi H, Kaneko Y, Kaneko T, Fujita K, Honma Y, Aoyagi T. A case of transient left ventricular ballooning with pheochromocytoma, supporting pathogenetic role of catecholamines in stress-induced cardiomyopathy or takotsubo cardiomyopathy. Int J Cardiol. 2007. 114:e15–e17.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download