Abstract

We aimed to evaluate the safety and clinical responses in Korean ankylosing spondylitis (AS) patients after three months of etanercept therapy. AS patients satisfying the Modified New York Criteria were enrolled. They were assessed for safety and clinical responses at enrollment and after three months of etanercept therapy. A total of 124 patients completed the study. After three months, the rate of ASsessment in AS International Working Group 20% improvement (ASAS 20) response was 79.8%. The rates of ASAS 40 and ASAS 5/6 responses were 58.5 and 62.8%, respectively. Significant improvement of Korean version of Bath AS Disease Activity Index (KBASDAI) (p<0.0001), Bath AS Functional Activity Index (BASFI) (p<0.0001), and Bath AS Metrology Index (BASMI) (p=0.0009) were achieved after three months. Quality of life was also significantly improved after three months, as demonstrated by scores for SF-36 (p<0.0001) and EQ-5D (p<0.0001). Erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein were significantly decreased (p<0.0001, p<0.0001, respectively). None of the patients developed tuberculosis and there were no serious adverse event. AS patients with inadequate response to conventional therapy showed significant clinical improvement without serious adverse events after three months of etanercept therapy.

Ankylosing spondylitis (AS) is a chronic, progressive, inflammatory disorder of unknown etiology that affects up to 1% of the population worldwide (1). It usually starts in sacroiliac joints with axial skeleton involvement as the disease progresses with inflammation of the joints and entheses eventually leading to new bone formation with syndesmophytes and ankylosis. Also, peripheral joint may be involved. It usually begins in late teens in Korea (2) and imposes considerable disease burden with disability and deformity (3).

Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) had been proven effective in AS (4), but unfortunately its efficacy is often unsatisfactory and a considerable number of patients are unable to maintain NSAIDs due to adverse events such as gastrointestinal disturbance or its effect on the cardiovascular system. Disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) such as sulfasalazine may be effective in peripheral arthritis, but there is no evidence that DMARDs are effective in axial involvement (5). Short-term effects of physical therapy in AS have been validated (6), but evidence for long-term effectiveness is lacking.

There have been numerous reports of tumor necrosis factor (TNF) playing an important role in AS. Mice transplanted with TNF-α expressing gene presenting joint symptoms similar to that of AS (7), and increase in serum TNF-α level in AS patients compared to other noninflammatory back pain patients have been reported (8). Increased expression of TNF-α mRNA and TNF protein in the sacroiliac joints demonstrated that TNF-α plays an important role in pathogenesis of AS and it was suggested that TNF blocker would be effective in treating AS (9).

Introduction of agents targeted against TNF, a proinflammatory cytokine, has provided an effective modality in treating AS. Both etanercept, a dimeric fusion protein of the TNF receptor and the Fc portion of IgG1, and infliximab, a monoclonal antibody that targets TNF, were significantly effective in improving pain and function in AS in randomized clinical trials (10-12). Adverse events related to TNF inhibitors includes injection site reactions, increased risk of infectionespecially tuberculosis (TB), development of antinuclear antibodies, lupus-like syndrome, demyelinating diseases, and worsening of preexisting congestive heart failure. Among these adverse events, injection site reaction is relatively common, especially with etanercept, but it usually diminished with repeated injections and does not pose a serious threat and incidence of TB have decreased with implementation of meticulous screening for TB and standardized guideline for treatment of latent TB in patients treated with TNF inhibitors.

In this work, we report results of clinical effectiveness measured by improvement in disease activity, function, metrologic measurements, acute phase reactants, and quality of life in both mental and physical domains after three months of etanercept therapy in Korean patients with AS.

A total of 132 AS patients fulfilling the modified New York criteria for the diagnosis of AS (13) initiating etanercept therapy due to lack of efficacy for NSAIDs and/or DMARDs were recruited consecutively from May 12th, 2005 to March 31st, 2006 at the Hospital for Rheumatic Diseases, Hanyang University. The patients included in the study were required to have severe active disease with inappropriate response to at least three consecutive months of treatment with NSAIDs and/or DMARDs as defined by a Korean version of Bath AS Activity Index (KBASDAI) (14) of over or equal to four and bilateral grade two or unilateral grade three sacroilitis. Patients who had received a biologic agent in the past were excluded.

All patients were screened for TB by detailed history, chest radiograph, and purified protein derivate tuberculin skin test (TST). Patients were required to have either negative result for TB or had received at least three weeks of prophylactic treatment for TB if tested positive for latent TB with induration of 10 mm or greater on TST. Patients with history of active TB, history of recent close contact with a known TB patient, or evidence of TB on chest radiograph were excluded. Patients with other rheumatologic diseases, chronic infection, congestive heart failure, or malignancy were also excluded. The study protocol was approved by institutional review board of Hanyang University Hospital and all patients provided written consent.

Etanercept was administered subcutaneously at a fixed dose of 25 mg twice a week for three months. DMARDs, NSAIDs, and steroids were either continued or discontinued according to the clinical judgment of the investigator.

The patients were evaluated for disease activity using the KBASDAI which assesses fatigue, spinal pain, joint pain, joint swelling, areas of localized tenderness, and morning stiffness, C-reactive protein (CRP), and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR). Functional limitation was evaluated using Bath AS Functional Activity Index (BASFI), which assesses activities related to functional anatomy, and the patient's ability to cope with everyday life (15). Spinal movement was evaluated using Bath AS Metrology Index (BASMI), which measures cervical rotation, tragus to wall distance, lumbar side flexion, modified Schober's, and intermalleolar distance (16). Short Form Health Survey-36 (SF-36) and EuroQol 5 Dimensions (EQ-5D) (17) were used to evaluate the quality of life.

Primary endpoint was the percentage of ASsessment of Ankylosing Spondylitis International Working Group 20% response criteria (ASAS20) responders (18) after three months. ASAS20 response is defined as at least a 20% and 10 mm visual analog scale (VAS) improvement on a 0-100 scale in at least three of four following domains without worsening of 20% or greater or 10 mm or greater VAS on a 0-100 scale in the remaining fourth domain: physical function measured by BASFI, spinal pain measures on a 0-100 mm VAS, patient global assessment in the last week measured on a 0-100 mm VAS, and inflammation measured as the mean of intensity and duration of morning stiffness on KBASDAI.

Secondary endpoints included ASAS40 response defined as at least a 40% and 20 mm VAS improvement on a 0-100 scale in at least three of four domains described in ASAS20 without worsening of 40% or greater or 20 mm or greater VAS on a 0-100 scale in the remaining fourth domain (18), ASAS five out of six response defined as 20% improvement in five out of six following domains without deterioration in the sixth domain: pain, patient global assessment, function, inflammation, spinal mobility, and CRP (19), ASAS partial remission defined as an absolute score smaller than two in all of four ASAS domains (18), and improvement in KBASDAI, BASFI, BASMI, ESR, CRP, SF-36, and EQ-5D after three months. Concomitant medications were also assessed.

Patients were assessed for adverse events at three months by physical examination performed by the investigator, laboratory tests including complete blood cell count, liver function test, renal function test, and chest radiograph.

A total of 124 patients completed the three month assessment and eight patients were lost to follow-up due to personal reasons. The mean age was 32.4 yr with a male predominance of 84.1% and the mean disease duration was 14.0 yr and 90.2% of the patients were positive for HLA-B27. The percentage of patients with history of uveitis was 38.6% and 52.3% had peripheral joint involvement (Table 1). Sixteen patients (12.9%) had a history of completely treated pulmonary TB with no active lesions on their chest radiography and 41 patients (33.1%) were tested positive to the TST. All patients have reported having been vaccinated with Bacillus of Calmette and Guérin. Those tested positive to TST with an induration greater than 10 mm were diagnosed as latent TB and prophylactic treatment for TB with isoniazid 300 mg once daily for nine months was initiated. They were initiated on etanercept therapy after three weeks of prophylaxis therapy according to the Guideline for the Treatment of Latent TB in Patients Receiving Biologic Agents set forth by the Korean Center for Diseases Control (20). All patients had significant AS diseases activity with KBASDAI score of at least 4. Health-related quality of life was also substantially lower than in the general population (21). SF-36 physical and mental component summary scores were low with 28.8 ±7.5 and 31.3±10.3, respectively, compared to 82.6±17.0 and 76.6±19.2, respectively, in the general Korean population (21) (Table 2). EQ-5D scores were also lower with EQ-5D profile score and VAS of 0.5±0.2 and 4.0±2.0, respectively, compared to 0.9±0.1 and 75.1±15.3, respectively, in the general Korean population (22) (Table 2).

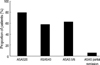

After three months, ASAS 20 was achieved in 99 of 124 patients (79.8%). ASAS 40, ASAS 5/6, and ASAS partial remission were achieved in 73 (58.9%), 77 (62.1%), and 8 (6.5%) patients, respectively (Fig. 1). There were no significant differences in ASAS response criteria according to disease duration.

Significant improvement in KBASDAI score was achieved after three months (p<0.001) and BASFI and BASMI scores also showed a significant improvement (p<0.001, for both comparisons) (Table 2). Only 14 (9.9%) patients failed to show a KBASDAI score of less than four after three months. Significant improvement was achieved in all domains of the KBASDAI with the neck, back, and hip pain domain showing the greatest improvement followed by the morning stiffness intensity domain (Table 2). Improvements in BASMI domains were less significant with the cervical rotation and intermalleolar distance domains failing to reach significance (Table 3).

Health-related quality of life also improved significantly in both the SF-36 and EQ-5D (p<0.001, for both comparisons) (Table 2). Improvements were significant in all domains. CRP and ESR also improved significantly after 3 months (p<0.001, for both comparisons) (Table 2).

At three months, patients taking NSAIDs decreased from 98.5% to 44.7%, methotrexate from 55.3% to 38.6%, sulfasalazine 47.0% to 6.1%, and steroids 29.5% to 6.8%.

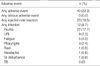

Forty (32.3%) patients experienced an adverse event. The most common treatment-related adverse event was localized infusion site reaction including pruritis and rash. Upper respiratory infection was the second most common adverse event. None of the patients developed TB during the study. No serious adverse events occurred. There were no clinically significant changes in the values in serum chemistry, hematology or urine laboratory test, or vital signs.

This study was from a prospective cohort of patients who started on etanercept treatment for treatment of AS at our hospital. The patients in our cohort were from diverse geographic location all over Korea and can be representative of the general Korean AS population. There has been long-term extended studied of etanercept (23, 24), but the patients included were from short-term randomized trials with strict inclusion criteria and cannot represent the general population. Therefore, although the study was relatively short in duration of follow-up, it provides the insight on efficacy and safety of etanercept in real life until further long-term study is available. The results were consistent with previous controlled study of etanercept (25-27). Efficacy tended to be marginally better and adverse events were also not more frequent or severe compared to the controlled trials with confined inclusion criteria. This study showed that etanercept for treatment of AS was effective in decreasing pain and disease activity, and also improving physical function and healthrelated quality of life. The improvement was apparent in all domains with the greatest improvement in the morning stiffness intensity followed by neck, back, or hip pain in KBASDAI and the least improvement in intermalloeolar distance in BASMI. BASMI score as a whole improved significantly, but the significance was lost when indices were compared individually, except for lumbar flexion. This was to be expected since BASMI primarily measures structural damage and correlates poorly with functional outcome (28). Whether etanercept can reverse structural damage or not is still under investigation and even if it does have such an effect it would not be evident only after three months of therapy. In an analysis of two randomized controlled trials infliximab (29) and etanercept (10) for predictive factor for response to treatment with TNF blocker showed that shorter disease duration, younger age, lower BASFI score, and higher ESR and CRP correlated with better responses (30). However, no single demographic, functional, laboratory, or quality of life factor correlated with favorable response in our study. TNF blockers are effective in improving symptoms, physical function, mental well-being, quality of life, and may possibly prevent deforming complications, but once ankylosis develops it is considered irreversible. So, TNF blockers should be used without delay in AS patients with inadequate response to NSAIDs. Unfortunately, even TNF blockers are not universally effective in all AS patients with less than 80% of the patient achieving ASAS20 response criteria. Adverse events also occurs and although there was no serious adverse events after three months therapy, over 30% of patients experienced minor adverse events.

Reactivation of TB are of great concern (31) especially in relative TB endemic areas. Prophylactic treatment of latent TB has been shown to be effective in preventing active TB in patients receiving biologic agents (32) and it is recommended by the Korean Center for Diseases Control. Sixteen (12.1%) patients in this study had a history of TB and 41 (33.1%) were tested positive on TST. However, with TB prophylaxis there was no incidence of TB. But this was only a three-month follow-up study and since TB tends to occur later in the course of treatment with etanercept, further extended follow-up is needed to be able to draw a conclusion on TB risk associated with etanercept use in AS.

It has been only ten years since the introduction of etanercept, but anti-TNF agents have revolutionized the treatment of AS. Preliminary studies have even demonstrated short term radiographic improvements on magnetic resonance images with these agents. However, long-term follow-up will be needed to answer long-term effects and adverse events.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Proportion of patients achieving ASAS Criteria. ASAS, Assessment in ankylosing spondylitis working group.

Table 2

Improvements in outcome measures from baseline

KBASDAI, Korean version of Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Activity Index; BASFI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Activity Index; BASMI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Metrology Index; HRQoL, Health-Related Quality of Life; SF-36, Short form-36; EQ-5D, EuroQol 5 Dimensions; VAS, visual analog scale; CRP, C-reactive protein; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate.

References

1. Ahearn JM, Hochberg MC. Epidemiology and genetics of ankylosing spondylitis. J Rheumatol Suppl. 1988. 16:22–28.

2. Lee JH, Jun JB, Jung S, Bae SC, Yoo DH, Kim TY, Kim SY, Kim TH. Higher prevalence of peripheral arthritis among ankylosing spondylitis patients. J Korean Med Sci. 2002. 17:669–673.

3. Boonen A, van der Heijde D, Landewe R, Guillemin F, Rutten-van Molken M, Dougados M, Mielants H, de Vlam K, van der Tempel H, Boesen S, Spoorenberg A, Schouten H, van der Linden S. Direct costs of ankylosing spondylitis and its determinants: an analysis among three European countries. Ann Rheum Dis. 2003. 62:732–740.

4. Sturrock RD, Hart FD. Double-blind cross-over comparison of indomethacin, flurbiprofen, and placebo in ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1974. 33:129–131.

5. Chen J, Liu C. Is sulfasalazine effective in ankylosing spondylitis? A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. J Rheumatol. 2006. 33:722–731.

6. Dagfinrud H, Kvien TK, Hagen KB. Physiotherapy interventions for ankylosing spondylitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004. CD002822.

7. Crew MD, Effros RB, Walford RL, Zeller E, Cheroutre H, Brahn E. Transgenic mice expressing a truncated Peromyscus leucopus TNF-alpha gene manifest an arthritis resembling ankylosing spondylitis. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 1998. 18:219–225.

8. Gratacos J, Collado A, Filella X, Sanmarti R, Canete J, Llena J, Molina R, Ballesta A, Munoz-Gomez J. Serum cytokines (IL-6, TNF-alpha, IL-1 beta and IFN-gamma) in ankylosing spondylitis: a close correlation between serum IL-6 and disease activity and severity. Br J Rheumatol. 1994. 33:927–931.

9. Braun J, Bollow M, Neure L, Seipelt E, Seyrekbasan F, Herbst H, Eggens U, Distler A, Sieper J. Use of immunohistologic and in situ hybridization techniques in the examination of sacroiliac joint biopsy specimens from patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Arthritis Rheum. 1995. 38:499–505.

10. Gorman JD, Sack KE, Davis JC. Treatment of ankylosing spondylitis by inhibition of tumor necrosis factor alpha. N Engl J Med. 2002. 346:1349–1356.

11. Calin A, Dijkmans BA, Emery P, Hakala M, Kalden J, Leirisalo-Repo M, Mola EM, Salvarani C, Sanmarti R, Sany J, Sibilia J, Sieper J, van der Linden S, Veys E, Appel AM, Fatenejad S. Outcomes of a multicentre randomised clinical trial of etanercept to treat ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2004. 63:1594–1600.

12. van der Heijde D, Dijkmans B, Geusens P, Sieper J, DeWoody K, Williamson P, Braun J. Efficacy and safety of infliximab in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: results of a randomized, placebo-controlled trial (ASSERT). Arthritis Rheum. 2005. 52:582–591.

13. van der Linden S, Valkenburg HA, Cats A. Evaluation of diagnostic criteria for ankylosing spondylitis. A proposal for modification of the New York criteria. Arthritis Rheum. 1984. 27:361–368.

14. Garrett S, Jenkinson T, Kennedy LG, Whitelock H, Gaisford P, Calin A. A new approach to defining disease status in ankylosing spondylitis: the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index. J Rheumatol. 1994. 21:2286–2291.

15. Calin A, Garrett S, Whitelock H, Kennedy LG, O'Hea J, Mallorie P, Jenkinson T. A new approach to defining functional ability in ankylosing spondylitis: the development of the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index. J Rheumatol. 1994. 21:2281–2285.

16. Jenkinson TR, Mallorie PA, Whitelock HC, Kennedy LG, Garrett SL, Calin A. Defining spinal mobility in ankylosing spondylitis (AS). The Bath AS Metrology Index. J Rheumatol. 1994. 21:1694–1698.

17. Kim MH, Cho YS, Uhm WS, Kim S, Bae SC. Cross-cultural adaptation and validation of the Korean version of the EQ-5D in patients with rheumatic diseases. Qual Life Res. 2005. 14:1401–1406.

18. Anderson JJ, Baron G, van der Heijde D, Felson DT, Dougados M. Ankylosing spondylitis assessment group preliminary definition of short-term improvement in ankylosing spondylitis. Arthritis Rheum. 2001. 44:1876–1886.

19. Brandt J, Listing J, Sieper J, Rudwaleit M, van der Heijde D, Braun J. Development and preselection of criteria for short term improvement after anti-TNF alpha treatment in ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2004. 63:1438–1444.

20. Guideline for the treatment of latent tuberculosis in patients receiving biologic agents. Korea Food and Drug Administration. 2004. Available online at http://www.kfda.go.kr.

21. Yun JH, Kang JM, Kim KS, Kim SH, Kim TW, Park YW, Sung YK, Sohn JH, Song BJ, Uhm WS, Yoon HJ, Lee OY, Lee JH, Lee CB, Lee CH, Jung WT, Choe JY, Choi HS, Han DS, Bae SC. Health-related quality of life in Korean patients with chronic diseases. J Korean Rheum Assoc. 2004. 11:263–274.

22. Seong SS, Choi CB, Sung YK, Park YW, Lee HS, Uhm WS, Kim TH, Jun JB, Yoo DH, Lee OY, Bae SC. Health-related quality of life using EQ-5D in Koreans. J Korean Rheum Assoc. 2004. 11:254–262.

23. Brandt J, Listing J, Haibel H, Sorensen H, Schwebig A, Rudwaleit M, Sieper J, Braun J. Long-term efficacy and safety of etanercept after readministration in patients with active ankylosing spondylitis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2005. 44:342–348.

24. Braun J, Brandt J, Listing J, Zink A, Alten R, Burmester G, Golder W, Gromnica-Ihle E, Kellner H, Schneider M, Sorensen H, Zeidler H, Reddig J, Sieper J. Long-term efficacy and safety of infliximab in the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis: an open, observational, extension study of a three-month, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2003. 48:2224–2233.

25. Baraliakos X, Brandt J, Listing J, Haibel H, Sorensen H, Rudwaleit M, Sieper J, Braun J. Outcome of patients with active ankylosing spondylitis after two years of therapy with etanercept: clinical and magnetic resonance imaging data. Arthritis Rheum. 2005. 53:856–863.

26. Braun J, Bollow M, Remlinger G, Eggens U, Rudwaleit M, Distler A, Sieper J. Prevalence of spondylarthropathies in HLA-B27 positive and negative blood donors. Arthritis Rheum. 1998. 41:58–67.

27. Davis JC Jr, Van Der Heijde D, Braun J, Dougados M, Cush J, Clegg DO, Kivitz A, Fleischmann R, Inman R, Tsuji W. Recombinant human tumor necrosis factor receptor (etanercept) for treating ankylosing spondylitis: a randomized, controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2003. 48:3230–3236.

28. Jauregui E, Conner-Spady B, Russell AS, Maksymowych WP. Clinimetric evaluation of the bath ankylosing spondylitis metrology index in a controlled trial of pamidronate therapy. J Rheumatol. 2004. 31:2422–2428.

29. Braun J, Brandt J, Listing J, Zink A, Alten R, Golder W, Gromnica-Ihle E, Kellner H, Krause A, Schneider M, Sorensen H, Zeidler H, Thriene W, Sieper J. Treatment of active ankylosing spondylitis with infliximab: a randomised controlled multicentre trial. Lancet. 2002. 359:1187–1193.

30. Rudwaleit M, Listing J, Brandt J, Braun J, Sieper J. Prediction of a major clinical response (BASDAI 50) to tumour necrosis factor alpha blockers in ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2004. 63:665–670.

31. Gomez-Reino JJ, Carmona L, Valverde VR, Mola EM, Montero MD. Treatment of rheumatoid arthritis with tumor necrosis factor inhibitors may predispose to significant increase in tuberculosis risk: a multicenter active-surveillance report. Arthritis Rheum. 2003. 48:2122–2127.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download