Abstract

Vertebrobasilar junction entrapment due to a clivus fracture is a rare clinical observation. The present case report describes a 54-yr-old man who sustained a major craniofacial injury. The patient displayed a stuporous mental state (Glasgow Coma Scale [GCS]=8) and left hemiparesis (Grade 3). The initial computed tomography (CT) scan revealed a right subdural hemorrhage in the frontotemporal region, with a midline shift and longitudinal clival fracture. A decompressive craniectomy with removal of the hematoma was performed. Two days after surgery, a follow-up CT scan showed cerebellar and brain stem infarction, and a CT angiogram revealed occlusion of the left vertebral artery and entrapment of vertebrobasilar junction by the clival fracture. A decompressive suboccipital craniectomy was performed and the patient gradually recovered. This appears to be a rare case of traumatic vertebrobasilar junction entrapment due to a longitudinal clival fracture, including a cerebellar infarction caused by a left vertebral artery occlusion. A literature review is provided.

Fractures of the clivus are very rare, occurring in only 0.55% of head injury patients. Clival fractures are classified as longitudinal, transverse, or oblique. Longitudinal fractures are associated with a 67-80% mortality rate (1, 2), apparently due to vertebrobasilar artery occlusion (3-9) and direct brain stem trauma (10, 11). There are only 11 reported cases of vertebrobasilar artery entrapment or prolapse associated with longitudinal clivus fractures. Eight of those cases were only identified at autopsy, while the other 3 cases (12-14) survived but had various neurological deficits.

The present report describes a rare case of traumatic vertebrobasilar junction entrapment due to a longitudinal clival fracture. The patient was treated using surgical decompression of the left cerebellar infarction caused by the left vertebral artery occlusion. The patient survived and showed an improved Glasgow coma scale (GCS) score.

A 54-yr-old man sustained major craniofacial injuries following a traffic collision. The patient was riding bicycle and landed face-down on a hard road surface. He presented with severe right facial and ocular swelling, and profuse cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) rhinorrhea. Neurological findings included a stuporous mental state (GCS=8) and left hemiparesis (Grade 3). Brain and facial computed tomography (CT) revealed a comminuted fracture of the right frontal bone and anterior skull base extending to the clivus posteriorly, inferior and medial orbital wall fractures with extension to the maxillary sinus, diffuse but predominantly right-sided subdural hematoma, and a right-sided parenchymal frontotemporal hemorrhagic contusion with a 6.65 mm midline shift to the left side (Fig. 1). The initial CT scan demonstrated no cerebellar or brainstem lesion.

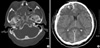

The patient underwent surgical decompression and removal of the hematoma. After surgery, the patient showed decreased consciousness (GCS=5), aggravated left hemiparesis (Grade 2), and worse right arm and leg response (Grade 3) under noxious stimuli. A brain CT scan on the second postoperative day demonstrated low-density lesions in the left cerebellum and lateral pons (Fig. 2), indicating a left posterior inferior cerebellar artery (PICA) territory infarction. A CT angiogram (Fig. 3A) and its source images (B) revealed the right vertebral artery (a, b), and the entrapped vertebrobasilar junction (c, d) and basilar artery (e).

A transfemoral conventional angiogram showed obstruction of the left vertebral artery in the cervical region (Fig. 4).

The patient underwent a suboccipital decompressive craniectomy and a C1 laminectomy in order to widen the foramen magnum (Fig. 5). The patient initially made a fair recovery in terms of consciousness and quadriparesis. At one month after surgery, the patient had normal cognitive function. A tracheostomy had to be maintained. The patient remained dependent in terms of daily living activities, and required a wheelchair for movement.

Fractures in the clivus are usually associated with high-impact blunt head trauma. While longitudinal clivus fractures are associated with a 67-80% mortality, transverse or oblique fractures have a better prognosis but are still associated with cranial nerve deficits. They are sometimes associated with carotid artery injury (1, 2).

Menku et al. identified nine cases involving clival fractures from the CT scans of 2,500 head injury patients. Five of those patients had longitudinal fractures, and three of them died (15). Corradino et al. reported 17 cases of clival fracture from the CT scans of 3,000 head injury patients. Six patients had longitudinal fractures. There were four deaths among them, including a case involving a trapped vertebral artery according to the vertebral angiogram (2). Joslyn et al. identified 11 cases of clival fracture from another series of 2,000 head injury patients. Five patients had longitudinal fractures, and four of those five died (1). All of the three aforementioned reports suggested that vascular injury affecting the posterior circulation was a key reason for such a high mortality rate.

To date, there have only been 11 confirmed cases (including Corradino's case) of longitudinal clival fractures associated with prolapse or entrapment of the vertebrobasilar arteries (Table 1). Most of those cases were fatal. Autopsy results in several cases showed complete occlusion of the prolapsed artery within the fracture, or thrombosis of the proximal basilar artery (2-7, 10-13). In the present case, even though there was occlusion of the left vertebral artery and narrowing of the vertebrobasilar junction according to the CT angiogram, there was good distal basilar arterial flow. Thus, the degree of brain stem and cerebellar infarction was manageable. In addition, the decompressive suboccipital craniectomy was probably helpful in reducing brain stem compression caused by the infarction.

In the current study, CT angiography was used to confirm the diagnosis of vascular entrapment. However, in most other cases, the patients died almost instantaneously as a result of the injury, and further imaging studies were not possible. Magnetic resonance (MR) angiography may reveal vascular occlusion and other additional findings in some cases (13, 14).

Clival fractures are created as a result of three potential directional forces: frontal, occipital, or axial impact (14). Sights et al. suggested (3) that frontal impact contributes to multiple facial fractures, and temporary deformation and an increased coronal dimension create a longitudinal clival fracture, such as that seen in the present patient. Occipital impact may have a similar mechanism in the formation of a longitudinal fracture (1, 8, 9). A direct blunt injury to the vertex may cause enough axial force to form a fracture (3, 6, 9).

Clivus fractures may be under-diagnosed due to the difficulty of demonstrating them on plain head radiographs. However, current bony window CT imaging has clearly shown the condition is not as infrequent as previously believed (9). The longitudinal subgroup of clival fractures is considered vulnerable. A CT angiogram is an essential diagnostic work-up in terms of associated vascular injury. In selected cases, surgical decompression may be helpful to reduce brain stem and cerebellar compression.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Initial CT scan showing a longitudinal clivus fracture extending from the frontal basal skull fracture (A), and an acute subdural hemorrhage with a partial midline shift in the right frontotemporal region (B).

Fig. 3

CT angiogram (A) and its source images (B). White arrows indicate the right vertebral artery (a), entrapped vertebrobasilar junction (b, c) and basilar artery (d, e).

References

1. Joslyn JN, Mirvis SE, Markowitz B. Complex fractures of the clivus: Diagnosis with CT and clinical outcome in 11 patients. Radiology. 1988. 166:817–821.

2. Corradino G, Wolf AL, Mirvis S, Joslyn J. Fractures of the clivus: Classification and clinical features. Neurosurgery. 1990. 27:592–596.

3. Sights WP Jr. Incarceration of the basilar artery in a fracture of the clivus. case report. J Neurosurg. 1968. 28:588–591.

4. Lindenberg R. Incarceration of a vertebral artery in the cleft of a longitudinal fracture of the skull. case report. J Neurosurg. 1966. 24:908–910.

5. Loop JW, White LE Jr, Shaw CM. Traumatic occlusion of the basilar artery within a clivus fracture. Radiology. 1964. 83:36–40.

6. Anthony DC, Atwater SK, Rozear MP, Burger PC. Occlusion of the basilar artery within a fracture of the clivus. case report. J Neurosurg. 1987. 66:929–931.

7. Shaw CM, Alvord EC Jr. Injury of the basilar artery associated with closed head trauma. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1972. 35:247–257.

8. Sato H, Sakai T, Uemura K. A case of incarceration of the vertebral and basilar arteries in a longitudinal fracture of the clivus. No Shinkei Geka. 1990. 18:1147–1150.

9. Sato S, Iida H, Hirayama H, Endo M, Ohwada T, Fujii K. Traumatic basilar artery occlusion caused by a fracture of the clivus-case report. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 2001. 41:541–544.

10. Zhu BL, Quan L, Ishida K, Taniguchi M, Oritani S, Fujita MQ, Maeda H. Longitudinal brainstem laceration associated with complex basilar skull fractures due to a fall: an autopsy case. Forensic Sci Int. 2002. 126:40–42.

11. Sato M, Kodama N, Yamaguchi K. Post-traumatic brain stem distortion: a case report. Surg Neurol. 1999. 51:613–616.

12. Guha A, Fazl M, Cooper PW. Isolated basilar artery occlusion associated with a clivus fracture. Can J Neurol Sci. 1989. 16:81–83.

13. Taguchi Y, Matsuzawa M, Morishima H, Ono H, Oshima K, Hayakawa M. Incarceration of the basilar artery in a longitudinal fracture of the clivus: case report and literature review. J Trauma. 2000. 48:1148–1152.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download