Abstract

Loa loa is unique among the human filariae in that adult worms are occasionally visible during subconjuntival migration. A 29-yr-old African female student, living in Korea for the past 5 yr without ever visiting her home country, presented with acute eyelid swelling and a sensation of motion on the left eyeball. Her symptoms started one day earlier and became worse over time. Examination revealed a threadlike worm beneath the left upper bulbar conjunctiva with mild eyelid swelling as well as painless swelling of the right forearm. Upon exposure to slit-lamp illumination, a sudden movement of the worm toward the fornix was noted. After surgical extraction, parasitologic analysis confirmed the worm to be a female adult Loa loa with the vulva at the extreme anterior end. On blood smear, the microfilariae had characteristic features of Loa loa, including sheath and body nuclei up to the tip of the tail. The patient also showed eosinophilia (37%) measuring 4,100/µL. She took ivermectin (200 µg/kg) as a single dose and suffered from a mild fever and chills for one day. This patient, to the best of our knowledge, is the first case of subconjunctival loiasis with Calabar swelling in Korea.

The filarial parasite Loa loa causes a chronic infection in humans that has two very characteristic clinical features: Calabar swellings (localized angioedema found predominantly on the extremities) and subconjuctival migration of the adult parasites ("eyeworm") (1). Loa loa is endemic in Central and West Africa. Since two initial reports of suspected loiasis in Korea (2, 3), there have been no further cases. We report a case of loiasis occurring in an African (Mauritanian) female living in Korea for the past five years with a history of staying in Cameroon for four years before arriving in Korea. The diagnosis was made by the removal of an adult Loa loa worm from the eye and the presence of microfilaremia and Calabar swelling.

A 29-yr-old female patient suffered from sudden eyelid swelling and a sensation of motion on the left eyeball, persisting for one day. She found a moving threadlike worm at the upper bulbar conjunctiva on the visiting day using a mirror. The patient's past medical and surgical history was unremarkable. She was born in Mauritius in East Africa, and had lived in Korea for the past five years without ever visiting her home country. From 1996 to 2000, before coming to Korea, however, she had been in Cameroon, which is included in the endemic area of the identified parasite.

Upon exposure to slit-lamp illumination, a sudden movement of the worm toward the fornix was noted. During the dim slit-lamp examination, a long threadlike worm was confirmed in the subconjuctival space. Painless swelling (oval, 5 × 3.5 cm) on the right forearm was also noted on physical examination.

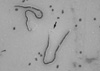

Under minimal illumination and with topical anesthesia, the presumed organism was grasped tightly with surgical toothed forceps. A 2-mm horizontal conjuctival incision was made while grasping the worm. A 5.8-cm long, 0.72-cm diameter worm was extracted through the conjuctival incision. Parasitologic analysis confirmed the worm to be a threadlike female adult Loa loa, with the vulva located at about 3 mm from the anterior end (Fig. 1). Blood analysis showed eosinophilia (37%, 4100/µL). Microfilariasis was detected using the Knott method, which allows up to 1 mL of blood to be concentrated per 10 mL of 2% formalin so that the sediment can be examined with Giemsa stain for microfilariae. Microfilariae were sheathed and averaged 261.1 µm in length. When stained, the body nuclei were continuous to the tip of the tail (Fig. 2).

After complete surgical extraction of the worm, eyelid swelling and Calabar swelling of the right forearm improved. Ivermectin (200 µg/kg) was prescribed for a single dose to prevent recurrence after confirmation of systemic microfilariasis. She presented with mild fever and chills for one day after taking the ivermection. The Calabar swelling completely disappeared within three days after taking medication.

The patient departed from Korea owing to unavoidable circumstances, and so long-term follow-up was not available.

Loa loa is restricted to Africa, with a distribution that stretches from south-eastern Benin in the west to southern Sudan and Uganda in the east, and from a latitude of 10° N to, perhaps, Zambia in the south (4). The adult worms live and migrate in the subcutaneous and deep connective tissues, and the microfilariae are found in the blood, where they can be ingested by mango flies or deerflies (Chrysops spp.). Once ingested by a fly, the microfilariae become infective in approximately 10 to 12 days. Humans are infected when the larvae enter the skin through bites by infected flies. Development into adult worms takes about 6 to 12 months, and they can survive up to 17 yr. The first clinical signs may occur as soon as 5 months post-infection (5) but clinical prepatency may last up to 13 yr (6). In this case, the patient's country of origin, Mauritius, is not reported to be an endemic area. She did have a history of staying in Cameroon for four years, which is probably where she became infected with the worm, before her arrival in Korea.

Adult Loa migrate actively throughout the subcutaneous tissue of the body and derive their popular name (eye worm) from the fact that they are most conspicuous and irritating when crossing the conjunctiva. Calabar swellings, named for the coastal Nigerian town where they were first recorded, may be several inches in diameter and is a type of allergic reaction to the metabolic products of the worms or to dead worms. These swellings can occur anywhere, but are more frequently seen on the limbs, especially the forearms. Painless swelling (oval, 5 × 3.5 cm) on the right forearm was observed in this patient.

One of the main characteristics of human infection with Loa is that a certain proportion of subjects with a recorded history of eye worm remain amicrofilaremic (7, 8). Therefore, loiasis may be suggested by the presence of fugitive swelling in association with high eosinophilia in persons who have visited or lived in endemic areas (9). Two Korean patients previously reported in Korea had a history of either living in Nigeria or traveling to Cameroon, and had Calabar swellings on their forearm or leg, high eosinophilia, and high antibody titer without microfilaremia (2, 3).

Loa-specific IgG4 measurement by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) to detect an occult infection is reportedly not very sensitive (10, 11). The best technique currently available for the diagnosis of loiasis, especially occult infection, is PCR for the detection of species-specific sequences of the repeat-3 region of the gene encoding a 15-kDa protein (12-14).

For the detection of microfilaria, we used the Knott's concentration technique, which hemolyzes the red blood cells and concentrates leukocytes and microfilariae (15), allowing us to observe moving microfilariae on the blood smear.

Loiasis can be effectively treated by surgical removal of the worms, leading to complete recovery. The most favorable removal time is when the worms are migrating through the corneal conjunctiva or across the bridge of the nose. In the present case, removal of the eye worm relieved Calabar swelling of the right forearm. Ivermectin was also administered for the elimination of microfilariae. The Calabar swelling completely disappeared within three days after taking the medication.

It should be noted that ivermectin treatment administered at the standard dose (150 µg/kg) may induce serious adverse events including encephalopathy, which may be fatal, in patients with very high Loa loa microfilaremia (16, 17).

Our patient did not exhibit high microfilaremia or other side effects except fever and chills. Long-term follow-up of this patient was not available because she departed from Korea owing to unavoidable circumstances.

As international exchange (including travel) makes the distinction between endemic and nonendemic areas less meaningful, Loa loa infection should be considered in the differential diagnosis for patients with eosinophilia and Calabar swelling in Korea.

In summary, we described a case with subconjunctival loiasis and Calabar swelling on the limbs treated with surgical excision of the worm and an oral course of ivermectin.

Figures and Tables

References

1. Klion AD, Massougbodji A, Sadeler BC, Ottesen EA, Nutman TB. Loiasis in endemic and nonendemic populations: immunologically mediated differences in clinical presentation. J Infect Dis. 1991. 163:1318–1325.

2. Min DY, Soh CT, Yoon JW. A case of Calabar swelling suspected as loiasis. Korean J Parasitol. 1987. 25:185–187.

4. Boussinesq M, Gardon J. Prevalences of Loa loa microfilaraemia throughout the area endemic for the infection. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1997. 91:573–589.

5. Churchill DR, Morris C, Fakoya A, Wright SG, Davidson RN. Clinical and laboratory features of patients with loiasis (Loa loa filariasis) in the U.K. J Infect. 1996. 33:103–109.

6. Thomas J, Chastel C, Forcain L. Latence clinique et parasitaire dans les filarioses a Loa loa et a Onchocerca volvulus. Bull Soc Pathol Exot Filiales. 1970. 63:90–94.

7. Toure FS, Deloron P, Egwang TG, Wahl G. Relation entre intensite de la transmission de la filaire Loa loa et prevalence des infections. Med Trop (Mars). 1999. 59:249–252.

8. Pion SD, Demanou M, Oudin B, Boussinesq M. Loiasis: the individual factors associated with the presence of microfilaraemia. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 2005. 99:491–500.

9. Beaver PC, Jung RC, Cupp EW. Loa loa. Clinical Parasitology. 1984. Washington: Lea & Febiger;377–380.

10. Toure FS, Mavoungou E, Deloron P, Egwang TG. Analyse comparative de deux methods diagnostiques de la loase humaine: serologie IgG4 et PCR niche. Bull Soc Pathol Exot. 1999. 92:167–170.

11. Klion AD, Vijaykumar A, Oei T, Martin B, Nutman TB. Serum immunoglobulin G4 antibodies to the recombinant antigen, Ll-SXP-1, are highly specific for Loa loa infection. J Infect Dis. 2003. 187:128–133.

12. Toure FS, Egwang TG, Wahl G, Millet P, Bain O, Georges AJ. Species-specific sequence in the repeat 3 region of the gene encoding a putative Loa loa allergen: a diagnostic for occult loiasis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1997. 56:57–60.

13. Toure FS, Kassambara L, Williams T, Millet P, Bain O, Georges AJ, Egwang TG. Human occult loiasis: improvement in diagnostic sensitivity by the use of a nested polymerase chain reaction. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1998. 59:144–149.

15. John DT, Petri WA Jr. Examination of blood, other body fluids and tissues, sputum, and urine. Markell and Voge's Medical Parasitology. 2006. St. Louis: Saunders Elsevier;422.

16. Gardon J, Gardon-Wendel N, Demanga-Ngangue , Kamgno J, Chippaux JP, Boussinesq M. Serious reactions after mass treatment of onchocerciasis with ivermectin in an area endemic for Loa loa infection. Lancet. 1997. 350:18–22.

17. Boussinesq M, Gardon J, Gardon-Wendel N, Chippaux JP. Clinical picture, epidemiology, and outcome of Loa-associated adverse events related to mass ivermectin treatment of onchocerciasis in Cameroon. Filaria J. 2003. 2:Suppl 1. S4.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download