Abstract

The patient was a 44-yr-old man with end-stage renal disease who had developed chorea as a result of hypoglycemic injury to the basal ganglia and thalamus and who was subsequently diagnosed with depression and restless legs syndrome (RLS). For proper management, the presence of a complex medical condition including two contrasting diseases, chorea and RLS, had to be considered. Tramadol improved the pain and dysesthetic restlessness in his feet and legs, and this was gradually followed by improvements in his depressed mood, insomnia, lethargy, and feelings of hopelessness. This case suggests that the dopaminergic system participates intricately with the opioid, serotoninergic, and noradrenergic systems in the pathophysiology of RLS and pain and indirectly of depression and insomnia.

The patient in this report was suffering from diabetic neuropathy, end-stage renal disease, restless legs syndrome (RLS), and depression. He had injuries of both basal ganglia and the thalamus as a result of hypoglycemia, causing chorea and more severe leg pains and dysesthetic sensations. RLS is a sensorimotor disorder characterized by unpleasant leg sensations together with an irresistible inner urge to move. Chorea is a neurological syndrome characterized by abrupt involuntary movements resulting from a continuous flow of random muscle contractions. The first-line pharmacological treatment for RLS is a dopaminergic agent, whereas anti-dopaminergic drugs are the main pharmacological treatment for chorea. In general, greater D2-receptor blocking action results in greater anti-choreic efficacy (1). Dopaminergic drugs for RLS would aggravate the choreic movements, while anti-dopaminergic agents for the treatment of chorea would exacerbate the RLS. In this report, the association between the complex medical conditions and symptoms of a patient with two coexisting, opposing diseases is discussed. This report also introduces the process through which proper diagnoses and treatments were sought.

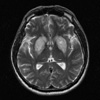

A 44-yr-old man with insomnia and depression was referred to the psychiatric department of our institution. He complained that he rarely fell asleep because of dysesthetic sensations and pain in the lower legs and feet and that he was depressed and feeling hopeless. Although he was aware of having had a high blood sugar level for 10 yr, he never sought treatment. About 3 yr earlier, in summer 2003, he began to experience cold, numbing, and pins-and-needles sensations on his toes that eventually spread throughout his feet. About a year later, he started taking hypoglycemic agents. However, the pain in his feet became severe, and restlessness as a result of creeping sensations in his lower legs gradually started to occur when he was lying down or sitting awake. He tried massaging and beating his legs and walking around. The unpleasant sensations and restlessness were temporarily relieved by massage and walking, but the pain in his feet remained little changed. These dysesthetic sensations were most severe when he lay down to sleep, increasing his sleep latency to longer than one hour. He woke repeatedly and had a difficulty falling back asleep because of further dysesthetic sensations. In July 2005, the patient received hemodialysis for end-stage renal disease. In those days his serum hemoglobin, iron, and ferritin levels were 7.4 g/dL, 29 µg/dL, and 97 ng/mL, respectively, so oral iron supplementation was administered. He gradually became depressed, experienced feelings of worthlessness, lost his appetite, and eventually stopped eating. His speech became slow, and his arms and legs trembled and twitched involuntarily. Subsequently, he showed irregular, spasmodic, involuntary movements in his limbs and on his face. He was taken to the emergency center of St. Vincent's Hospital on 26 June 2006 by his son. His blood sugar level was very low (49 mg/dL). T2- and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR)-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans showed high signal changes over the bilateral basal ganglia and right thalamus, although abnormal enhancing lesions were not found after contrast infusion (Fig. 1). The patient was diagnosed with hypoglycemic injury of both basal ganglia and the right thalamus and received conservative medical treatment. One week later, he presented to the psychiatric department complaining of depression and insomnia. He was depressed and feeling hopeless and had severe sleep disturbance and thoughts of suicide. He was transferred to the psychiatric ward. He complained that the most distressing problem was the difficulty in falling asleep and staying asleep because of the dysesthetic restlessness. He satisfied the diagnostic criteria for RLS in the International Classification of Sleep Disorders (2). He was prescribed citalopram 20 mg for depression, gabapentin 900 mg, and clonazepam 0.5 mg for peripheral neuropathy and RLS, oral iron supplements for iron deficiency anemia and RLS, and haloperidol 1.5 mg for choreic movements, and received daily supportive psychotherapy. Also, he received hemodialysis three times a week.

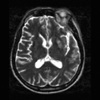

The dysarthria and involuntary hyperkinetic movements gradually improved over his whole body, except for his left arm. The pain in his feet remained severe, and the dysesthetic restlessness continued in his lower legs. He still suffered from insomnia and depression. Four weeks later, follow-up T2-weighted MRI scans showed resolution of previously noted basal ganglia lesions, residua of the hyperintensity change in the left putamen, and an infarction as an old lesion in the right thalamus (Fig. 2). The patient showed increased deep tendon reflexes on neurological examination as well as delayed latencies and small amplitudes for complex muscle action potential and sensory nerve action potential on a nerve conduction test, suggesting peripheral polyneuropathy. He then underwent a nocturnal polysomnography to examine the causes of his insomnia. When he lay down for polysomnographic evaluation, he experienced dysesthetic sensations and an irresistible inner urge to move his legs, as usual. The patient complained that he could not endure the dysesthetic sensations and was given his usual medications before bed: gabapentin 300 mg, clonazepam 0.5 mg, citalopram 10 mg, and haloperidol 1.5 mg. The patient fell asleep 18.3 min after taking the medications. His total sleep time was 391.0 min, and sleep efficiency was 80.4%. There were 55.2 periodic limb movements per hour in sleep, and about 36% of them led to arousal. The complete diagnoses of the patient included chorea, peripheral polyneuropathy, RLS, periodic limb movement disorder, insomnia, and depression. During those days, his serum hemoglobin, iron, and ferritin levels were nearly normal: 11.4 g/dL, 62.0 µg/dL, and 210.0 ng/mL, respectively.

Although gabapentin, clonazepam, oral iron supplements, citalopram, and haloperidol were prescribed for 4 weeks, the pain, dysesthetic sensations, insomnia, and depression continued. To make matters worse, the choreic movements were aggravated. An increase in the dosage of haloperidol from 1.5 to 3 mg was prescribed. However, the choreic movements did not improve, and the dysesthetic restlessness, insomnia, and depression worsened. The haloperidol was reduced to 1.5 mg, and the gabapentine was replaced with carbamazepine 400 mg and topiramate 25 mg. However, there was no improvement after 2 weeks. Consequently, carbamazepine and topiramate were replaced with tramadol 150 mg, while maintaining haloperidol 1.5 mg, citalopram 20 mg, and clonazepam 0.5 mg. After the first administration of tramadol, the pain, dysesthetic restlessness, difficulty in initiating sleep, frequent awakenings, and difficulty in falling back to sleep after an awakening slightly improved, and then gradually improved further, followed by improvements in the depressed mood, lethargy, markedly decreased volition and appetite, and feelings of hopelessness.

Peripheral neuropathy is a disorder that needs to be differentiated from RLS because both conditions include some similar symptoms; however, it is also a main cause of secondary RLS (3). The patient's dysesthetic sensations in the present case improved with movement but worsened in the evening. The pain continued regardless of movement or time. The findings in his nerve conduction test also supported the presence of peripheral polyneuropathy. As a result, he was thought to have both disorders.

Although its pathophysiology is not completely understood, circumstantial evidence exists for the role of the dopaminergic system in the pathophysiology of RLS (4). A positron emission tomography (PET) (5) study and a single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) (6) study showed significantly decreased striatal D2 receptor activity. Also, there is circumstantial evidence for the role of iron in the pathophysiology of RLS (7). Tyrosine hydroxylase is the rate-limiting enzyme in the production of dopamine and requires iron as a cofactor for hydroxylation of tyrosine (8). Therefore, iron deficiency may reduce dopamine production in the brain indirectly, while dopaminergic agents are effective in therapy for idiopathic RLS (9). The patient had conditions that would cause RLS, such as end-stage renal disease, iron deficiency, and peripheral neuropathy, and then to make matters worse, he was injured in the basal ganglia and thalamus by hypoglycemia. Following the hemodialysis treatment for the end-stage renal disease, his symptoms of RLS were aggravated, and after the brain injury, choreic movements developed and symptoms of RLS became extremely severe. In this case, iron deficiency due to ESRD with hemodialysis and poor nutrition might lead to decreased production of dopamine, and it would have caused RLS. In addition, the injury of the basal ganglia might have raised a further decrease of dopamine, aggravating RLS.

Chorea results from various dysfunctions within the complex neural network interconnecting the basal ganglia-thalamus-motor cortex (10). In the present case, the choreic movements developed after injuries to the basal ganglia and thalamus and decreased as the injuries recovered, although the movements remained owing to the thalamic infarct. Because anti-dopaminergic drugs are used to treat chorea, dopaminergic agents for RLS could not be used in this case. Gabapentin was prescribed, but the chorea grew worse. Most studies have reported that gabapentin improved pain and dysesthetic sensations without the risk of dyskinesia, but some studies found that gabapentin induced dyskinesia or even chorea. These reports hypothesized that increased gabanergic input may precipitate more motor facilitation through the thalamus (11), augment dopaminergic activity in the striatum (12), or indirectly raise the concentration of serotonin (13).

The patient experienced alleviation of his pain, dysesthetic sensations, and insomnia after being prescribed tramadol, which produces both opioid and non-opioid analgesic effects. Tramadol acts on the central nervous system and is known to have an effect on opioid receptors, especially the µ receptor, and serotonergic and noradrenergic transporters. The positive pharmacological response to an opioid and the exacerbation of RLS by the opiate receptor blocker naloxone support the hypothesis that dysfunction of the endogenous opiate system is connected to the pathophysiology of RLS (14). Few studies have examined the effect of tramadol on RLS (15). The present case was remarkable because of the risk associated with using dopaminergic or gabanergic drugs given the patient's complicated medical condition and the observation that tramadol was an effective treatment. The positive effect of tramadol may originate not only from its action on opioid receptors but also through increased activities of dopamine, serotonin, and noradrenalin. However, not only the effect of tramadol but also the recovery from the injury of the basal ganglia, iron supplement, and improvement of depression may contribute to the alleviation of the symptoms of RLS. This case suggests that the dopaminergic system participates intricately with the opioid, serotonergic, and noradrenergic systems in the pathophysiology of RLS and pain and indirectly of depression and insomnia.

Figures and Tables

References

1. Cardoso F, Seppi K, Mair KJ, Wenning GK, Poewe W. Seminar on choreas. Lancet Neurol. 2006. 5:589–602.

2. American Academy of Sleep Medicine. International classification of sleep disorders. Diagnostic and coding manual. 2005. 2nd ed. Westcher, IL: American Academy of Sleep Medicine;81–86.

3. Polydefkis M, Allen RP, Hauer P, Earley CJ, Griffin JW, McArthur JC. Subclinical sensory neuropathy in late-onset restless legs syndrome. Neurology. 2000. 55:1115–1121.

4. Allen RP, Earley CJ. Restless legs syndrome. A review of clinical and pathophysiologic features. J Clin Neurophysiol. 2001. 18:128–147.

5. Turjanski N, Lees AJ, Brooks DJ. Striatal dopaminergic function in restless legs syndrome: 18F-dopa and 11C-raclopride PET studies. Neurology. 1999. 52:932–937.

6. Michaud M, Soucy JP, Chabli A, Lavigne G, Montplaisir J. SPECT imaging of striatal pre- and postsynaptic dopaminergic status in restless legs syndrome with periodic leg movements in sleep. J Neurol. 2002. 249:164–170.

7. Allen RP, Earley CJ. Restless legs syndrome: a review of clinical and pathophysiologic features. J Clin Neurophysiol. 2001. 18:128–147.

8. Mizuno S, Mihara T, Miyaoka T, Inagaki T, Horiguchi J. CSF iron, ferritin and transferrin levels in restless legs syndrome. J Sleep Res. 2005. 14:43–47.

9. Brodeur C, Montplaisir J, Godbout R, Marinier R. Treatment of restless legs syndrome and periodic movements during sleep with Ldopa: a double-blind, controlled study. Neurology. 1988. 38:1845–1848.

10. DeLong MR. Primate models of movement disorders of basal ganglia origin. Trends Neurosci. 1990. 13:281–285.

11. Loescher W, Hoenack D, Taylor CP. Gabapentin increases aminooxyacetic acid-induced GABA accumulation in several regions of rat brain. Neurosci Lett. 1991. 128:150–154.

12. Agid Y, Bonnet AM, Ruberg M, Javoy-Agid F. Pathophysiology of L-dopa-induced abnormal involuntary movements. Psychopharmacology. 1985. 2:(Suppl). 145–159.

13. Rao ML. Gabapentin augments whole blood serotonin in healthy young men. J Neural Transm. 1988. 73:129–134.

14. Walters AS. Review of receptor agonist and antagonist studies relevant to the opiate system in restless legs syndrome. Sleep Med. 2002. 3:301–304.

15. Lauerma H, Markkula J. Treatment of restless legs syndrome with tramadol: an open study. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999. 60:241–244.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download