Abstract

Drug Rash with Eosinophilia and Systemic Symptoms (DRESS) syndrome reflects a serious hypersensitivity reaction to drugs, characterized by skin rash, fever, lymph node enlargement, and internal organ involvement. So far, numerous drugs such as sulfonamides, phenobarbital, sulfasalazine, carbamazepine, and phenytoin have been reported to cause the DRESS syndrome. We report a case in a 29-yr-old female patient who had been on celecoxib and anti-tuberculosis drugs for one month to treat knee joint pain and pulmonary tuberculosis. Our patient's clinical manifestations included fever, lymphadenopathy, rash, hypereosinophilia, and visceral involvement (hepatitis and pneumonitis). During the corticosteroid administration for DRESS syndrome, swallowing difficulty with profound muscle weakness had developed. Our patient was diagnosed as DRESS syndrome with eosinophilic polymyositis by a histopathologic study. After complete resolution of all symptoms, patch tests were positive for both celecoxib and ethambutol. Although further investigations might be needed to confirm the causality, celecoxib and ethambutol can be added to the list of drugs as having the possibility of DRESS syndrome.

Drug hypersensitivity syndrome (DHS) refers to a severe, potentially life-threatening, drug reaction. To better individualize this drug reaction, the term "Drug Rash with Eosinophilia and Systemic Symptoms (DRESS) syndrome" has recently been used.

DRESS syndrome was first introduced in 1996 by Bocquet et al. (1). Fever, rash, lymphadenopathy, and internal organ involvement with marked eosinophilia constitute the main manifestations. The most frequently involved organ is the liver, followed by the kidney and lungs. The most frequently incriminated drugs are anticonvulsant, sulfonamides, dapsone, allopurinol, minocycline, and gold salt. The pathophysiology of DRESS syndrome remains unclear, but a defect in detoxification of causative drug, immunological imbalance, and infections such as human herpes virus type 6 (HHV 6) have been suggested (2). The overall mortality in DRESS is about 10% and occurrs in patients with severe multi-organ involvement (1).

We report here a case of DRESS syndrome induced by celecoxib and anti-tuberculosis (Tb) drugs including isoniazid, rifampicin, ethambutol, and pyrazinamide in a patient presented first as knee joints pain.

A 29-yr-old woman with no prior known medical illness presented on March 2004 with an oral ulcer and knee joint pain. She had no specific past medical history before. Celecoxib was prescribed by a rheumatologist on 17 March under the suspicion of arthritis.

During the course of routine clinical examination, one pulmonary nodule was found in the left upper lung field on chest radiography. High-resolution lung computed tomography (CT) suggested active pulmonary tuberculosis. She was treated with isoniazid, rifampicin, ethambutol, and pyrazinamide from March 25th. On April 28th (34 and 42 days after the initiation of anti-Tb drugs and celecoxib, respectively), she was hospitalized due to jaundice and hepatomegaly.

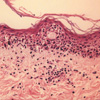

On admission, her temperature was 38℃, blood pressure was 90/60 mmHg, and heart rate was 90 beats per min. She had an exanthematous rash on her trunk and limbs with some pustules (Fig. 1), decreased bibasilar lung sound, icteric sclera, hepatosplenomegaly, cervical lymphadenopathy, and posterior pharyngeal wall injection. Blood cell counts showed hemoglobin 12.4 g/dL, leukocyte count 19,990/µL (polymorphs 45.6%, lymphocytes 28.4%, and eosinophils 12.4% [upper limit of normal (ULN) 6%]), and platelet count 261,000/µL. On her peripheral blood smear, neutrophilic leukocytosis with eosinophilia was noted without atypical lymphocytosis. Laboratory data at the patient's first admission are summarized in Table 1. Serologic tests for viral infections including hepatitis A and B, Epstein-Barr virus, human immunodeficiency virus, and cytomegalovirus were negative. Auto-antibody screening revealed negative antinuclear antibody (ANA) and anti-smooth-muscle antibody (SMA). A skin biopsy (Fig. 2) showed intraepidermal eosinophil infiltration and spongiosis with pustule formation. Perivascular inflammatory cell cuffing was also noted. The chest radiography showed right pleural effusion with pneumonic consolidation. The previous nodule in the left upper lung showed no interval change. DHS was suspected and all anti-Tb drugs and celecoxib were stopped. Intravenous methylprednisolone (1,000 mg daily) for DHS and antimicrobial therapy (intravenous ceftriaxone 2 g daily and amikacin 1 g daily) for pneumonia were administered for 5 days, followed by oral prednisone 75 mg daily and ursodeoxycholic acid 200 mg three times daily. Fever and rash gradually resolved and liver function started to improve. She was discharged on day 19 (17 May).

Seven days later (24 May), the patient was readmitted. She took her medicine intermittently after discharge. She presented with a rash on forearm, sore throat, myalgia, swallowing difficulty, and dyspnea. Over the next 3 days, she was febrile up to 38℃, and the rash extended to whole body with vesicle and pustule formation. Laboratory findings at second admission are also outlined in Table 1. The CT scan of abdomen showed hepatomegaly with perihepatic fluid collection. A bone marrow biopsy disclosed moderate hypercellular marrow with diffuse infiltration of eosinophils.

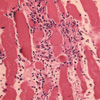

The diagnosis of a recurrent DRESS syndrome was made, and methylprednisolone 1,000 mg daily was infused intravenously for 3 days. On day 4 of readmission, myalgia and swallowing difficulty became more profound and muscle weakness developed. Right biceps muscle biopsy (Fig. 3) showed diffuse endomysial and perimysial infiltration of eosinophils with myonecrosis. Her serum creatine kinase (CK) increased up to 18,943 IU/L (ULN 217 IU/L), and electromyography showed typical myopathic changes. Tests were negative for SMA and anti Jo-1 antibodies. A diagnosis of eosinophilic polymyositis was made. Intravenous cyclosporine 100 mg daily and oral methylprednisolone 60 mg daily were initiated. However, respiratory muscle weakness exacerbated requiring mechanical ventilatory support with intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) infusion (1 g/kg/day for 2 days) on day 8 of readmission. After 2 weeks of mechanical ventilation, her respiratory function improved and the ventilator was weaned. At that time, a trans bronchial lung biopsy disclosed chronic granulomatous inflammation without significant eosinophilic infiltrate and a sputum AFB stain revealed a positive finding. Anti-Tb treatment with second-line drugs (cycloserine 500 mg daily, ofloxacin 400 mg daily, prothion-amide 250 mg daily, and streptomycin 1 g five times weekly) was restarted on June 12th, and cyclosporine was discontinued on June 27th. After two more cycles (each cycle included 2 days of immunoglobulin infusion [1 g/kg/day]) of IVIG, skin lesions and liver function improved. The prednisone was gradually tapered to 40 mg daily, and the patient was discharged on July 9th.

Over the next two months, the prednisone dosage was reduced to 20 mg daily and an azathioprine (AZT) 50 mg daily was added on August 27th because her serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) level was fluctuating and we worried about the side effect of long-term steroid therapy in the patient with Tb. Two weeks after initiation of AZT, she had a return of fever, up to 37.6℃, jaundice, and a tender liver. Laboratory findings at the third admission showed a cholestatic pattern, which was common in AZT toxicity (Table 1). AZT was stopped on September 12th, and only oral prednisone was maintained at a dosage of 10 to 20 mg daily with one more cycle of IVIG. Afterwards, the serum ALT level became normalized and complete resolution of all symptoms was achieved 14 months after discontinuation of the celecoxib and first line anti-Tb drugs. Prednisone was completely tapered in June 2005.

Four weeks after discontinuation of the prednisone, patch-testing was performed with the celecoxib and first-line anti-Tb drugs to evaluate a causal relationship. Tablets were crushed and incorporated at 10% and 50% in white petrolatum. The results showed diffuse erythematous rash around the celecoxib, rifampicin, and ethambutol at day 2. Then, the rash was localized to the celecoxib and ethambutol at day 4, and it was more prominent near the celecoxib (Fig. 4). Taken together, her episode was more likely induced by the celecoxib which probably played a major contributory role, and other first-line anti-Tb drugs played a minor contributory role. Second-line anti-Tb drugs were administered until October 2005. Her liver function had been completely normalized without recurrence of symptoms, and follow-up lung CT also showed complete resolution of pulmonary Tb.

Our patient was diagnosed as DRESS syndrome as defined by Bocquet et al. (1). Clinical features were typical: fever, lymphadenopathy with pharyngitis, rash followed by exfoliative dermatitis, hypereosinophilia >1,500/µL, and visceral involvement (hepatitis and pneumonitis). The symptoms began 34 and 42 days after the introduction of anti-Tb drugs and celecoxib, respectively, in our patient.

The side effects reported with celecoxib have been generally benign exanthemas. Recently, two cases of severe drug hypersensitivity syndrome due to celecoxib have been reported (3). In both cases, the celecoxib patch tests were positive. In the first 2 yr of marketing, the reporting rate for Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis with celecoxib was 6 cases per million person-years of use (4). The reporting rate was somewhat higher than the background rate of 1.9 cases per million population per year. In our patient, celecoxib was not suspected at first as the causative drug, but in the patch test it showed stronger reaction than other anti-Tb drugs.

Celecoxib, a selective cyclo-oxygenase-2 inhibitor, is a diaryl-substituted pyrazole derivative containing a sulfonamide substituent. Sulfonamide is one of the most frequently incriminated drugs in DRESS syndrome. The aromatic amine portion of the sulfonamide is considered to be critical in the development of hypersensitivity syndrome. Since celecoxib does not contain the aromatic amine, adverse reactions such as hypersensitivity syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis would not be expected to occur at the same frequency as they do with sulfonamides. Reports showing lack of cross-reactivity balance the few case reports suggesting cross-reactivity (5). In the present case, we also considered the possibility of transferring the aromatic amine portion from anti-Tb drugs to celecoxib, but we did not verify such a reaction in vitro.

Our patient's patch tests were positive to both celecoxib and ethambutol. In the test, rifampicin also showed positive reaction on day 2 but disappeared on day 4, then interpreted as an irritant reaction. However, the patch test result is not a confirmative one, and the rifampicin allergy with a negative patch test also has been reported previously (6).

Ethambutol is a relatively safe drug. In a study by Pitt (7), there were less than 2% of adverse reactions in the 2,000 patients who received 15 mg/kg ethambutol. Skin reactions due to ethambutol included hair loss, urticaria, erythema multiforme, angioedema, hyperhidrosis, skin striae, bullous eruptions, and exfoliative dermatitis (8). But a severe cutaneous reaction of toxic epidermal necrolysis associated with ethambutol has been reported (9). In a review of the literature, we could not find other case report of DRESS syndrome attributable to ethambutol.

Clinical and pathologic findings of our patient were consistent with eosinophilic polymyositis (EM). Eosinophilic myositis is a clinically and pathologically diverse group of inflammatory muscle diseases associated with blood and/or tissue eosinophilia (10). Clinical presentation of EM is distinct from other eosinophilic myositis. Tender muscle swelling associated with proximal weakness accompanies a systemic illness. The etiologies of eosinophilic myopathy include parasitic infection, vasculitis, malignancies, and idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome. The pathogenesis remains unclear. An increase in eosinophil production and activation mediated by cytokines like interleukin (IL)-5 are thought to play an important role. Elevated muscle IL-5 induces local accumulation of eosinophils and the subsequent release of eosinophilic granular proteins. This eosinophilic degranulation is blocked by cyclosporin A and prednisone (11). In the same way, internal organ involvement by eosinophil infiltration in DRESS syndrome is also thought to be induced by IL-5. Systemic corticosteroids can inhibit the effect of IL-5 on eosinophil accumulation and reduce the symptoms of DRESS syndrome (12, 13).

In the present case, respiratory muscle weakness progressed resulting in the respiratory failure despite the cyclosporine infusion. Such a fulminant EM following DRESS syndrome is a rare association. IVIG with prednisone was administered after the onset of myositis, and the respiratory function resumed with the resolution of DRESS syndrome and polymyositis. In the previous reports on recurrent DRESS syndrome, IVIG administration showed improvement (14).

After complete resolution of our patient's symptoms, laboratory tests for anti-HHV 6 IgG antibody showed positive reaction but the polymerase chain reaction for HHV6 DNA was negative. So the confirmation of exact association with HHV6 was not made. If HHV6 reactivation was a possibility, our patient's recovery after IVIG therapy could be explained. Although the mechanism of IVIG treatment in DRESS remains unknown, the therapeutic effects might be dependent on functional capabilities of anti-virus IgG contained in IVIG. So far, the only undisputed way to treat severe DHS is prompt withdrawal of the offending drug. Systemic corticosteroid administration is classically reported in the case of organ- or life-threatening disease (15).

In a severe DHS as in present case, provocation test is not ethically recommended. Also, in such a case which involves multiple complexed drugs, patch test may be a useful method for detecting the culprit drugs (16). This approach has been advocated in previous reports on DRESS syndrome (17, 18).

In conclusion, we report here a case of DRESS accompanying EM, the cause of which might be associated with both celecoxib and ethambutol according to the patch test. Celecoxib and ethambutol can be added to the list of drugs causing DRESS syndrome, but further investigations including lymphocyte toxicity assay might be needed to confirm the causality.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 2Histologic examination shows intraepidermal eosinophil infiltration and spongiosis. Perivascular inflammatory cell cuffing is also noted. Hematoxylin and eosin stain (H&E), ×400. |

References

1. Bocquet H, Bagot M, Roujeau JC. Drug-induced pseudolymphoma and drug hypersensitivity syndrome (Drug Rash with Eosinophilia and Systemic Symptoms: DRESS). Semin Cutan Med Surg. 1996. 15:250–257.

2. Sullivan JR, Shear NH. The drug hypersensitivity syndrome: what is the pathogenesis. Arch Dermatol. 2001. 137:357–364.

3. Marques S, Milpied B, Foulc P, Barbarot S, Cassagnau E, Stalder JF. Severe cutaneous drug reactions to celecoxib (Celebrex). Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2003. 130:1051–1055.

4. La Grenade L, Lee L, Weaver J, Bonnel R, Karwoski C, Governale L, Brinker A. Comparison of reporting of Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis in association with selective COX-2 inhibitors. Drug Saf. 2005. 28:917–924.

5. Knowles S, Shapiro L, Shear NH. Should celecoxib be contraindicated in patients who are allergic to sulfonamides? Revisiting the meaning of sulfa allergy. Drug Saf. 2001. 24:239–247.

6. Strauss RM, Green ST, Gawkrodger DJ. Rifampicin allergy confirmed by an intradermal test, but with a negative patch test. Contact Dermatitis. 2001. 45:108.

7. Pitt FW. Hook EW, Mandell GL, Gwaltney JM, editors. Tuberculosis, prevention and therapy. Current concepts of infectious disease. 1977. New York: John Wiley & Sons;181–194.

8. Holdiness MR. Adverse cutaneous reactions to antituberculosis drugs. Int J Dermatol. 1985. 24:280–285.

9. Pegram PS Jr, Mountz JD, O'Bar PR. Ethambutol-induced toxic epidermal necrolysis. Arch Intern Med. 1981. 141:1677–1678.

10. Kaufman LD, Kephart GM, Seidman RJ, Buhner D, Qvarfordt I, Nassberger L, Gleich GJ. The spectrum of eosinophilic myositis. Clinical and immunopathogenic studies of three patients, and review of the literature. Arthritis Rheum. 1993. 36:1014–1024.

11. Meng Q, Ying S, Corrigan CJ, Wakelin M, Assoufi B, Mogbel R, Kay AB. Effects of rapamycin, cyclosporine A, and dexamethasone on interleukin 5-induced eosinophil degranulation and prolonged survival. Allergy. 1997. 52:1095–1101.

12. Ahn CM, Moon JH, Moon JG, Lee KM, Lee JH, Hong CS, Park JW. A case of cephalosporin-induced DRESS (Drug Rash with Eosinophilia and Systemic Symptoms) syndrome with acute renal failure. J Asthma Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005. 25:69–72.

13. Valencak J, Ortiz-Urda S, Heere-Ress E, Kunstfeld R, Base W. Carbamazepine induced DRESS syndrome with recurrent fever and exanthema. Int J Dermatol. 2004. 43:51–54.

14. Kano Y, Inaoka M, Sakuma K, Shiohara T. Virus reactivation and intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) therapy of drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome. Toxicology. 2005. 209:165–167.

15. Tas S, Simonart T. Management of drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS syndrome): an update. Dermatology. 2003. 206:353–356.

16. Kim CW, Choi GS, Yun CH, Kim DI. Drug hypersensitivity to previously tolerated phenytoin by carbamazepine-induced DRESS syndrome. J Korean Med Sci. 2006. 21:768–772.

17. Lachapelle JM, Maibach HI. Patch testing. Prick testing. A practical guide. 2003. Berlin: Springer.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download