Abstract

A 16-yr-old male patient with hemochromatosis due to multiple packed red blood cell transfusions was referred to our emergency center for the treatment of severe aplastic anemia and dyspnea. He was diagnosed with aplastic anemia at 11-yr of age. He had received continuous transfusions because an HLA-matched marrow donor was unavailable. Following a continuous, approximately 5-yr transfusion, he was noted to develop hemochromatosis. He had a dilated cardiomyopathy and required diuretics and digitalis, multiple endocrine and liver dysfunction, generalized bleeding, and skin pigmentation. A total volume of red blood cell transfusion before deferoxamine therapy was about 96,000 mL. He received a regular iron chelation therapy (continuous intravenous infusion of deferoxamine, 50 mg/kg/day for 5 days q 3-4 weeks) for approximately seven years after the onset of multiple organ failures. His cytopenia and organ dysfunctions began to be gradually recovered since about 2002, following a 4-yr deferoxamine treatment. He showed completely normal ranges of peripheral blood cell counts, heart size, and liver function two years ago. He has not received any transfusions for the last four years. This finding suggests that a continuous deferoxamine infusion may play a role in the immune regulation in addition to iron chelation effect.

Acquired aplastic anemia is characterized by the depletion of hematopoietic stem cells and progenitor cells, the hypocellularity of bone marrow and blood pancytopenia, and it commonly occurs in children and young adults (1). The standard treatments are hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) or immunosuppressive therapy in patients with life-threatening cytopenia. HSCT is the treatment of choice in young patients with an human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-matched sibling or unrelated stem cell donor and immunosuppressive therapy is indicated for patients without HLA-matched donor or older patients (1, 2). However, patients who relapsed despite these treatments or those who did not receive such active therapies depend on continuous blood transfusions, and they are ultimately fatal because of its natural clinical course, clonal evolution to other malignant diseases (3), or secondary complications such as hemochromatosis (4).

A very poor prognosis may be predicted in patients with severe aplastic anemia (SAA) in whom major organ failures occurred by multiple blood transfusions. Can the only supportive therapies such as blood component transfusions including packed red blood cell (PRBC) and continuous iron chelation be possible in normalizing the disease and recovering organ failures? The answer may be no. However, we experienced an interesting finding in a patient with SAA using a continuous iron chelation therapy. We expect that the therapy will be an alternative answer to this problem on the aspect of stem cell immunobiology. In addition, the same treatment protocol has been applied to other similar patients from our hospital, in whom a gradual improvement is being noted and a follow-up monitoring is needed.

In 1998, a 16-yr-old male patient visited our emergency center with a chief complaint of severe dyspnea. He was diagnosed with SAA at 11 yr of age. According to his medical record, his bone marrow was markedly hypocellular (<10% cellularity) without dysplastic features, and the Ham's and sucrose tests were negative. He received twice of ALG immunotherapies and supportive erythropoietin injections, but did not have any responses. He neither had an HLA-matched sibling stem cell donor nor found an unrelated stem cell donor despite continuous search. He was given oral oxymetholone and continuously had two pints of PRBC transfusion at a 1- to 2-week interval for five years while awaiting an HLA-matched unrelated stem cell donor. The total volume of PRBC (320-400 mL/pack) transfusion was approximately 96,000 mL during that period. Initial electrocardiography showed atrial fibrillation with a heart rate of 150/min. The chest radiography showed huge cardiomegaly with 80% of cardio-thoracic ratio and both pleural effusions (Fig. 1), and the erect and supine view of abdomen radiography showed a severe hepatomegaly. An echocardiographic examination presented 4% of left ventricular ejection fraction with severely dilated left ventricle and nearly akinetic cardiac wall movement. Laboratory tests showed 4.5 g/dL of hemoglobin, 20×109/L of absolute reticulocyte count, 2.7×109/L of white blood cell count (absolute neutrophil count, 0.3×109/L), 3×109/L of platelet count, 407 mg/dL of fasting blood glucose-level, and 68,800 ng/mL of serum ferritin.

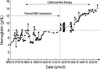

We immediately admitted him to our intensive care unit. He received appropriate doses of oxygen, digitalis, diuretics, and a continuous intravenous infusion of insulin in addition to levothyroxine, calcium, and vitamin D of his previous prescriptions. Other laboratory tests showed 0.37 ng/dL of serum free thyroxine (normal range, 0.8 to 1.9 ng/dL), 142.2 mIU/L of thyrotropin (normal range, 0.4 to 4 mIU/L), 6.0 mg/dL of serum calcium level (normal range, 8.2 to 10.2 mg/dL), 13 pg/mL of intact PTH (normal range, 15 to 70 pg/mL), and 8.4% of hemoglobin A1C (normal range, 4 to 6%). These findings were suggestive of multiple endocrine dysfunctions including hypothyroidism, hypoparathyroidism with hypocalcemia, and diabetes. Liver function tests were 2.5 mg/dL of serum total bilirubin, 2.8 g/dL of serum albumin, prolonged prothrombin time of 16.4 sec (normal range, 11.1 to 13.1 sec) and 1.437 INR (normal range, 0.9 to 1.12), 35.1 sec of activated partial thromboplastin time (normal range, 25 to 38 sec), 649 IU/L of serum aspartate aminotransferase (normal range, 8 to 40 IU/L), and 539 IU/L of serum alanine aminotransferase (normal range, 5 to 40 IU/L). Ophthalmologic examination confirmed a cataract in both eyes. Generalized skin pigmentation was seen in his skin. Abdominal ultrasonography showed severe hepatomegaly with increased parenchymal echogenecity. Based on these findings, he was diagnosed with secondary hemochromatosis accompanied by multiple organ failures which resulted from iron deposition in body organs due to multiple PRBC transfusions. Based on some published reports that iron chelation plays a prominent role in hemochromatosis (5, 6), he received a 12-hr continuous intravenous infusion of deferoxamine (50 mg/kg/day) for five days at a 4-week interval. He received PRBC during deferoxamine treatment, if necessary. He also received innumerable units of platelet concentrates. Thereafter, he was frequently admitted to the medical intensive care unit through our emergency center because of the aggravated symptoms and signs of heart failure and diabetes-related complications, multiple cerebral and subdural hematomas, and seizure. Meanwhile, he was being given a 7-yr deferoxamine treatment. The frequency of his hospitalization was markedly being lowered, and his hematologic profiles (Fig. 2) and heart size were beginning to nearly normalize after an approximately 4-yr deferoxamine treatment. His insulin requirement also decreased, and from then, a low-dose erythropoietin injection was initiated. Since then, he has only received outpatient care. He was noted to have completely normal ranges of peripheral blood cell counts, heart size, and liver functions two years ago. A defective expression of CD55/59 was not observed on either granulocytes or erythrocytes of peripheral blood. Since the event of complete response, his bone marrow aspirate and biopsy for the evaluation of bone marrow status has not been performed because of his strong refusal. He has not required any blood transfusions over the past four years (Fig. 3). He currently shows normal reference ranges of all hematologic and other laboratory tests.

The prognosis of SAA is very fatal if its therapy is the only supportive one such as transfusions. A few patients with aplastic anemia have been reported to recover spontaneously without specific therapy, but these remissions usually occur within the first 7 weeks and the remainder followed a rapidly fatal course (7). Only 1/3-1/2 of them may be alive six months after the diagnosis, and about 80% die within 18 months to two years as described in many reports. Even patients who survive infections or bleeding also lead to a dangerous situation because of secondary hemochromatosis associated with multiple major organ failures. It is very surprising that a continuous, several-year iron chelation combined with low-dose erythropoietin injection improves major organ dysfunctions and produces a complete recovery of hematologic abnormalities. Moreover, these promising results are being noted gradually in other two patients undergoing the similar disease situations.

It has been reported that iron chelator not only removes iron deposited in the tissues but also plays a role in immunologic mechanisms in spite of some controversy. Carotenuto et al. reported that deferoxamine acts as a blocker for IL-2 receptor of human T-lymphocytes, and Hoffbrand et al. indicated the immunosuppressive effect of deferoxamine in inhibiting the activity of ribonucleotide reductase in human lymphocytes (8, 9). These reports indicate the immunologic inhibitory effects of deferoxamine.

We have postulated that the deferoxamine treatment gradually had an immunologic influence on the suppressive environment of aplastic marrow and changed bone marrow stromal environment into positive hematopoiesis. In addition, erythropoietin therapy might have enhanced hematopoietic proliferation (10, 11). There are some evidences supporting our postulates: according to Aucella et al., the combination therapy using deferoxamine and recombinant erythropoietin promotes synergistically erythropoiesis in patients with chronic renal failure. Kling et al. also noted that iron deprivation increases erythropoietin production in normal subjects and patients with malignancy (12, 13). It is very surprising that a continuous iron chelation induces the recovery of organ dysfunctions. This was previously supported by Tsironi et al. who reported that combined iron chelation reversed heart failure in patients with thalassemia major (14). This makes us speculate that a continuous, long-term infusion of iron chelator can cause a partial or complete recovery of multiple organ failures due to iron deposition.

We suggest that an early introduction of continuous iron chelation could prevent secondary hemochromatosis due to multiple transfusions and also reverse their hematopoiesis by its immune modulation effect in patients with refractory or relapsed aplastic anemia who did not respond to any treatments, those who did not find an available HLA-matched stem cell donor, or those who relapsed into the original disease despite the treatments.

Figures and Tables

References

1. Keohane EM. Acquired aplastic anemia. Clin Lab Sci. 2004. 17:165–171.

2. Geissler K. Pathophysiology and treatment of aplastic anemia. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2003. 115:444–450.

3. Maciejewski JP, Risitano AM. Aplastic anemia: management of adult patients. Hematolgoy Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2005. 110–117.

4. Mwanda OW, Otieno CF, Abdalla FK. Transfusion haemosiderosis inspite of regular use of desferrioxamine: case report. East Afr Med J. 2004. 81:326–328.

5. Girot R, Thévenin M, Bouveret JP, Jeannel F, Rymer JC. Treatment of iron overload due to repeated transfusions with subcutaneous infusions of desferrioxamine. Arch Fr Pediatr. 1980. 37:241–247.

6. Cohen AR, Mizanin J, Schwartz E. Rapid removal of excessive iron with daily, high-dose intravenous chelation therapy. J Pediatr. 1989. 115:151–155.

7. Lee JH, Lee JH, Shin YR, Lee JS, Kim WK, Chi HS, Park CJ, Lee KH. Spontaneous remission of aplastic anemia: a retrospective analysis. Haematologica. 2001. 86:928–933.

8. Carotenuto P, Pontesilli O, Cambier JC, Hayward AR. Desferoxamine blocks IL 2 receptor expression on human T lymphocytes. J Immunol. 1986. 136:2342–2347.

9. Hoffbrand AV, Ganeshaguru K, Hooton JW, Tattersall MH. Effect of iron deficiency and desferrioxamine on DNA synthesis in human cells. Br J Haematol. 1976. 33:517–526.

10. Shao Z, Chu Y, Zhang Y, Chen G, Zheng Y. Treatment of severe aplastic anemia with an immunosuppressive agent plus recombinant human granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor and erythropoietin. Am J Hematol. 1998. 59:185–191.

11. Bessho M, Hirashima K, Asano S, Ikeda Y, Ogawa N, Tomonaga M, Toyama K, Nakahata T, Nomura T, Mizoguchi H, Yoshida Y, Niitsu Y, Kohgo Y; Multicenter Study Group. Treatment of the anemia of aplastic anemia patients with recombinant human erythropoietin in combination with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor: a multicenter randomized controlled study. Eur J Haematol. 1997. 58:265–272.

12. Aucella F, Vigilante M, Scalzulli P, Musto P, Prencipe M, Valente GL, Carotenuto M, Stallone C. Synergistic effect of desferrioxamine and recombinant erythropoietin on erythroid precursor proliferation in chronic renal failure. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1999. 14:1171–1175.

13. Kling PJ, Dragsten PR, Roberts RA, Dos Santos B, Brooks DJ, Hedlund BE, Taetle R. Iron deprivation increases erythropoietin production in vitro, in normal subjects and patients with malignancy. Br J Haematol. 1996. 95:241–248.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download