Abstract

Reactive lymphoid hyperplasia (RLH) of the liver is a rare entity and has also been termed nodular lymphoid lesion or pseudolymphoma of the liver. We report a case of hepatic RLH exhibiting unusual histiocyte-rich histologic features in a 47-yr-old woman in conjunction with a renal cell carcinoma. A follow-up computed tomography scan was done 14 months after a right radical nephrectomy for renal cell carcinoma revealed a nodular lesion in segment 5 of the liver. The lesion was interpreted as metastatic renal cell carcinoma or hepatocellular carcinoma based on the history of the patient and radiologic findings. Wedge resection of segment 5 was done with sufficient distance from the mass. Microscopically, the lesion was composed predominantly of peculiar histiocytic proliferation and was characterized by lymphoid aggregates forming a lymphoid follicle with germinal centers. The present case and prior cases reported in the literature suggest that RLH of the liver appear to be a heterogenous group of reactive inflammatory lesions that are often associated with autoimmune disease or malignant tumors.

Reactive lymphoid hyperplasia (RLH), known as pseudolymphoma, is a rare condition that has been observed in the liver. It is characterized by a marked proliferation of polyclonal and non-neoplastic lymphoid cells with the formation of abundant follicles that have active germinal centers (1, 2). It is usually localized and well demarcated from the surrounding tissue. RLH is thought to represent an immune-mediated reactive phenomenon, and may arise in association with a malignant tumor (2, 3). We report a case of RLH of the liver that mimicked a metastatic carcinoma, based on radiological findings in a patient with renal cell carcinoma. In particular, the histiocyte-rich RLH pattern observed in this case, which seems to be an uncommon feature of RLH, is discussed.

A 46-yr-old woman underwent a radical right nephrectomy for stage I renal cell carcinoma of the clear cell type. A followup computed tomography (CT) scan was done 14 months later and revealed a new mass in segment 5 of the liver. It was 1.0 cm in diameter and well-defined round-shaped mass showing high attenuation at arterial phase imaging and slight low attenuation at portal and equilibrium phase imaging. For further evaluation of this mass, a magnetic resonance (MR) examination was performed. On T2-weighted MR imaging, this mass showed an intermediate hyperintensity-like liver malignancy (Fig. 1A). On gadolinium-enhanced MR imaging, this mass showed bright nodular enhancement at arterial phase imaging (Fig. 1B) and peripheral rim-like enhancement at delayed phase imaging, which was interpreted as a metastatic renal cell carcinoma or hypervascular hepatocellular carcinoma. A physical examination and chest roentgenogram were unremarkable. Laboratory data were all within the normal range and the results of liver function tests were normal (aspartate aminotransferase [AST] 21 U/L, alanine aminotransferase [ALT] 33 U/L, total bilirubin 0.66 mg/dL, alkaline phosphatase 94 U/L, and lactate dehydrogenase [LDH] 154 U/L). A test for the hepatitis B antibody was positive. The level of carcinoembryonic antigen was 3.7 ng/mL (normal -5), and CA19-9 was slightly elevated (41.98 U/mL, normal -36). Alpha-fetoprotein levels and anti-mitochondrial antibodies were not available. A diagnosis of metastatic renal cell carcinoma from the previous renal cell carcinoma was presumed, based on the prior history of the patient and radiological findings, and wedge resection of segment 5 including the mass was performed ensuring adequate distance from the mass. Grossly, the resected liver segment contained a well-circumscribed, yellowish-white, solitary nodule of firm consistency, measuring 1 cm in diameter (Fig. 2A). Microscopically, the lesion was composed predominantly of a peculiar histiocytic proliferation without significant atypia and was characterized by lymphoid aggregates forming a lymphoid follicle with germinal centers (Fig. 2B, C). Most of the follicles were observed on the edge of the nodule. There was also marked hyalinization in part of the mass, and several bile ductules were observed on the edge of the nodule. In the surrounding liver tissue, a marked periductular fibrosis with prominent lymphocytic infiltration was also observed (Fig. 2B). However, the hepatic parenchyma distant from this nodule was normal and lymphoid infiltration was not detected in the portal tracts. The bile duct system contained no stones. Lymphoid cells positive for L-26 (B cell marker, DAKO, Glostrup, Denmark) were distributed mainly in the germinal centers, while those positive for UCHL-1 (T cell marker, DAKO) were present around the germinal centers. There were no cytokeratin-positive malignant epithelial cells in the nodule. CD68 (histiocyte marker, DAKO) immunostaining highlighted the large number of histiocytes with epithelioid cell features (Fig. 2D). HMB45 (marker for angiomyolipoma, DAKO)-positive cells were not detected. Use of special stains, such as periodic acid-Schiff, Grocott, and Ziehl-Neelsen stains failed to demonstrate any microorganisms in the lesion. A polymerase chain reaction analysis for mycobacteria was negative.

In the liver, RLH has also been variously termed as nodular lymphoid lesion (2, 4) and pseudolymphoma (5-9). A review of the literature has revealed that 17 cases of RLH of the liver have been reported to date (Table 1). Including the present case, the age of patients ranged from 36 to 85 yr (average, 60.5 yr). There was a female predilection with a female-to-male ratio of 8:1. In terms of underlying disease, chronic hepatitis (6, 8), autoimmune disease such as Sjogren's disease (9), chronic thyroiditis (10), primary biliary cirrhosis (2), CREST syndrome (2), and diabetes mellitus (1, 7) have been reported. Hence, autoimmune mechanisms seem to be most likely involved in the RLH occurrence.

By definition, the diagnosis of RLH is based on a polymorphous lymphocytic infiltration, and often numerous germinal centers, without cytologic atypia; however, on the basis of the published pathologic descriptions, this seemed to be variable both in extent and in cellular composition. In nine cases, lymphoid infiltration was seen in the portal areas around the nodule. However, including the current case, lymphoid infiltration was confined to the portal tracts immediately around the nodule; the rest of the hepatic parenchyma was normal, suggesting that this lesion was local rather than diffuse (1-3, 7, 10-13). We can speculate that several lymphoid follicles in these portal areas conglomerated and formed an RLH lesion. Few lymphoepithelial lesions were present (2, 4), and in one case Ig-light chain restriction has been observed by immunohistochemistry (2). However, there was no evidence of a monoclonal B cell population by molecular genetic analysis (2, 13). Tanizawa and colleagues reported a RLH of the liver characterized by an angiofollicular pattern with interfollicular hyalinization mimicking Castlemans desease (14). In five cases including the case reported here, hyalinized trabecular structures in the nodule were present (2, 11, 13, 14). The peculiar histiocytic proliferation in the present case consisted of a granulomatous arrangement of epithelioid histiocytes, which is similar to the characteristic features of a non-caseating granuloma. However, periodic acid-Schiff, Grocott, and Ziehl-Neelsen stains failed to demonstrate any microorganisms in the lesion. Furthermore, the histologic findings of lymphoid follicles with active germinal centers in our case are not seen in other granulomatous lesions, such as sarcoidosis. Among the RLH of the liver cases we reviewed, only one case exhibited aggregates of epithelioid histiocytes in the nodule as seen in the case presented here. These findings suggest that RLH of the liver appear to represent a heterogenous group of reactive inflammatory lesions that share a varying degree of inflammation, rather than a specific entity.

Including the present patient, seven cases of hepatic RLH accompanying malignant tumors have been reported (3, 5, 8, 11, 13): in two each cases of colon cancer (3) and gastric cancer (5, 8). One patient with multiple carcinomas (gastric, cecal, and colon cancer) has presented with hepatic RHL (13). Pantanowitz and colleagues have described an RLH of the liver in a patient with a renal cell carcinoma (11). Surprisingly, the histopathologic findings including the presence of lymphoid follicles with germinal centers, hyalinized trabecular structures, and lymphocytic infiltration in the portal tracts around the nodular lesion, are very similar to those seen in the present case. These findings suggest a possible correlation between hepatic RLH and renal cell carcinoma. However, there have been very few cases, so it is not clear whether the renal cell carcinoma was involved in the onset of the hepatic RLH. We can speculate that the etiology of RLH of the liver may be related to an immunologic abnormality that is caused by the malignant tumor itself or previous surgery for the tumors. The prognosis of the RLH associated with malignancies is good, and most patients treated by resection of this lesion have shown no recurrence or progression to lymphoma (3, 11).

Although our case showed some features of an inflammatory pseudotumor, it has other histologic findings that are not seen in an inflammatory pseudotumor, including the absence of fibroblastic proliferation, a lack of prominent fibrosis, collection of foamy histiocytes, or occlusive endophlebitis. Furthermore, the histologic features of inflammatory pseudotumors do not necessarily contain lymphoid follicles that are always found in RLH (7). Thus, our lesion is histologically different from an inflammatory pseudotumor.

Radiologically, RLH should be differentiated from other solid focal hepatic lesions as both conditions show intermediate hyper-intensity on T2-weighted MR imaging. In particular, the RLH in our case showed bright nodular enhancement on arterial phase MR imaging, which may be misinterpreted as hypervascular metastasis from a renal cell carcinoma or a hypervascular hepatocelluar carcinoma. The imaging findings of our case might be similar to those of previous reports demonstrating variable enhancement of RLH using contrastenhanced CT, CT during angiography, and direct hepatic angiography (3, 6, 8, 10, 12). However, since the imaging modalities used in published reports were variable, a further evaluation with a large number of cases will be required in order to define clearly the radiological findings of this entity.

Figures and Tables

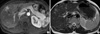

Fig. 1

(A) The respiratory-triggered T2-weighted turbo spin-echo MR imaging shows a small mass with intermediate high signal intensity (arrow) in liver segment 5. (B) The gadolinium-enhanced arterial phase MR imaging shows small bright nodular enhancement (arrow) in the same location as in A.

Fig. 2

(A) A cut section of the resected liver shows a well-circumscribed, yellowish-white mass in segment 5. (B) The lesion is composed predominantly of peculiar histiocytic proliferation and lymphoid aggregate forming lymphoid follicles on the edge of the nodule. Note the dense infiltrate of lymphocytes in several portal tracts immediately around the nodule (arrows, ×20, H&E). (C, D) The lesion is mainly composed of aggregates of epithelioid histiocytes simulating non-caseating granuloma (C ×200, D ×400, H&E). (E) Hyalinized structures in the nodule (arrow, ×200, H&E). (F) CD68 immunostaining highlights the large number of histiocytes (×200, CD68).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The author deeply appreciates Prof. M. Kojiro of Kurume University for his valuable advice and comments on histopathology.

References

1. Isobe H, Sakamoto S, Sakai H, Masumoto A, Sonoda T, Adachi E, Nawata H. Reactive lymphoid hyperplasia of the liver. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1993. 16:240–244.

2. Sharifi S, Murphy M, Loda M, Pinkus GS, Khettry U. Nodular lymphoid lesion of the liver: an immune-mediated disorder mimicking lowgrade malignant lymphoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 1999. 23:302–308.

3. Takahashi H, Sawai H, Matsuo Y, Funahashi H, Satoh M, Okada Y, Inagaki H, Takeyama H, Manabe T. Reactive lymphoid hyperplasia of the liver in a patient with colon cancer: report of two cases. BMC Gastroenterol. 2006. 6:–25.

4. Willenbrock K, Kriener S, Oeschger S, Hansmann ML. Nodular lymphoid lesion of the liver with simultaneous focal nodular hyperplasia and hemangioma: discrimination from primary hepatic MALT-type non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Virchows Arch. 2006. 448:223–227.

5. Grouls V. Pseudolymphoma (inflammatory pseudotumor) of the liver. Zentralbl Allg Pathol. 1987. 133:565–568.

6. Ohtsu T, Sasaki Y, Tanizaki H, Kawano N, Ryu M, Satake M, Hasebe T, Mukai K, Fujikura M, Tamai M, Abe K. Development of pseudolymphoma of liver following interferon-alpha therapy for chronic hepatitis B. Intern Med. 1994. 33:18–22.

7. Katayanagi K, Terada T, Nakanuma Y, Ueno T. A case of pseudolymphoma of the liver. Pathol Int. 1994. 44:704–711.

8. Kim SR, Hayashi Y, Kang KB, Soe CG, Kim JH, Yang MK, Itoh H. A case of pseudolymphoma of the liver with chronic hepatitis C. J Hepatol. 1997. 26:209–214.

9. Okubo H, Maekawa H, Ogawa K, Wada R, Sekigawa I, Iida N, Maekawa T, Hashimoto H, Sato N. Pseudolymphoma of the liver associated with Sjogren's syndrome. Scand J Rheumatol. 2001. 30:117–119.

10. Nagano K, Fukuda Y, Nakano I, Katano Y, Toyoda H, Nonami T, Nagasaka T, Hayakawa T. Reactive lymphoid hyperplasia of liver coexisting with chronic thyroiditis: radiographical characteristics of the disorder. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1999. 14:163–167.

11. Pantanowitz L, Saldinger PF, Kadin ME. Pathologic quiz case: Hepatic mass in a patient with renal cell carcinoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2001. 125:577–578.

12. Maehara N, Chijiiwa K, Makino I, Ohuchida J, Kai M, Kondo K, Moriguchi S, Marutsuka K, Asada Y. Segmentectomy for reactive lymphoid hyperplasia of the liver: report of a case. Surg Today. 2006. 36:1019–1023.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download