Abstract

Shwachman-Diamond syndrome (SDS) is an autosomal recessive genetic disorder, consisting of exocrine pancreatic insufficiency, chronic neutropenia, neutrophil chemotaxis defects, metaphyseal dysostosis, short stature, dental caries, and multiple organ involvements. Although SDS is the second most common hereditary abnormality of exocrine pancreas following cystic fibrosis in the Western countries, it has rarely been reported in Asia. We diagnosed a case of SDS in a 42-month-old girl, and genetic analysis including the relatives of the patient confirmed the diagnosis for the first time in Korea. She had short stature, steatorrhea, dental caries, and recurrent prulent otitis media and pneumonias. Laboratory studies revealed cyclic neutropenia, and serum levels of trypsin, amylase, and lipase were decreased. Simple radiography revealed metaphyseal sclerotic changes at the distal femur. A CT scan demonstrated a fatty infiltration and atrophy of the pancreas. On direct sequencing analysis of Shwachman-Bodian-Diamond Syndrome gene exon 2 region, the patient was homozygous for the c.258+2T>C mutation and heterozygous for the c.183_184TA>CT mutation and c.201A>G single nucleotide polymorphism. Treatment with pancreatic enzyme replacement, multivitamin supplementation, and regular to high fat diet improved her weight gain and steatorrhea.

Shwachman-Diamond syndrome (SDS; congenital pancreatic hypoplasia with hematological abnormalities; OMIM 260400) is an autosomal recessive disease with characteristics of exocrine pancreatic insufficiency, due to fatty infiltration and atrophy, short stature, and chronic neutropenia (1-3). After cystic fibrosis, SDS is the most common inherited cause of exocrine pancreatic dysfunction in the Western world. However, it has rarely been reported in Asia; only two cases of SDS have been reported in Korea: a child who died of hematological malignancy (4) and another case of a 21-yr-old woman who underwent allogeneic bone marrow transplantation (5).

The SDS phenotype is extremely heterogeneous, and specific features of this disease change with advancing age. Diagnosis is made primarily based on clinical symptoms, and for diagnostic confirmation, genetic analysis may be performed.

The recently discovered, causative gene for this disorder, Shwachman-Bodian-Diamond syndrome (SBDS) gene is located at chromosome 7q11 and contains five exons. A pseudo gene (SBDSP) has also been identified with a locally duplicated 305 kb genomic segment and 97% nucleotide identity with the disease-causing gene (6). Genetic analysis in Western patients has identified two common mutations: c.258+2T>C (p.84Cfs3), and c.183_184TA>CT (p.K62X), resulting from conversion of exon 2 segments (6).

We report a child with diverse clinical manifestations of SDS including short stature, steatorrhea, dental caries, skeletal system abnormalities, and neutropenia; the clinical diagnosis was confirmed by genetic analysis for the first time in Korea.

A 42-month-old girl was admitted to Konkuk university hospital because of steatorrhea and short stature. The patient was born at 36 weeks and four days of gestation with a birth weight of 2.5 kg (25-50 percentile) and height of 51 cm (90 percentile). There were no problems during the perinatal period; early growth and development were normal. However, at the age of about three months, she presented to the hospital with convulsion and neutropenia. Since then she has had frequent prulent otitis media and pneumonias. After teething, dental caries developed early; she required frequent dental treatment. During late infancy, steatorrhea with foul odor developed; the amount of stool was large for age. The patient had performed normal, active physical and cognitive activities for age. The family history was negative for similar clinical problems.

Her height was 87.7 cm (less than third percentile), weight was 11.5 kg (less than third percentile), head circumference was 48 cm (50th percentile), and the body proportions were appropriate. The vital signs were normal for age. She had angular stomatitis, and examination of the teeth revealed many dental caries and crown prostheses. The liver and spleen were not palpated. Examination of the musculoskeletal system and neurological examinations were all normal.

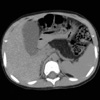

The results of the laboratory studies were as follows: hemoglobin 11.3 g/dL, leukocytes 3,000/µL (neutrophils 17.3%, lymphocytes 59.5%, monocytes 22.9%, basophils 0.3%, and eosinophils 0%), platelets 152 K/µL, serum amylase less than 30 U/dL, serum lipase 15 U/L, serum trypsin 38 ng/mL, glucose 88 mg/dL, aspartate aminotransferase (AST) 61 IU/L, alanine aminotransferase (ALT) 40 IU/L, prothrombine time (PT) 78% (INR 1.19), and activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) 48.3 sec. Serum calcium, phosphate, total protein, and albumine levels and urinalysis were normal; the size of fat in stool was increased (170 µm). On radiological examination, the bone age was 27 months; transverse sclerotic changes were detected at the metaphysis of distal femurs. On the abdominal CT scan, marked fatty infiltration of the pancreas was detected (Fig. 1). A small bowel series revealed no abnormality.

Genetic analysis of the patient and her relatives was performed. The sequence of the primer for Sbds2D1 was AAATGGTAAGGCAAATACGG and primer for Sbds2R was ACCAAG TTCTTTATTATTAGAAGTGAC (7). The genotype of the patient was homozygous for the c.258+2T>C mutation and heterozygous for the c.183_184TA>CT mutation and c.201A>G single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP); her father and paternal grandmother were heterozygous for the c.183_184TA>CT; 258+2T>C mutations, and c.201A> G SNP, and her mother was heterozygous for the c.258+2T>C mutation. The patient's younger twin brothers, grandfather, and paternal aunt revealed wild-type sequence in exon 2 region of the SBDS gene (Fig. 2, 3).

Initially, the patient was treated with parenteral nutrition, with pancreatic enzyme replacement (Beasae®, Daewoong pham., Seoul, Korea, 1 tablet: higher than 20,000 USP unit amylase, higher than 25,000 USP unit protease, 15,000 IU) based on the amount of lipase required for age, and with multivitamins (Alvityl syrup®, Youngjin phama., Seoul, Korea), while providing normal to high-fat diet. The amount of feces decreased, the consistency became harder, and malodor also decreased. The size of fat in stool decreased. The patient's weight increased to 12.7 kg, and she was discharged from the hospital. In the outpatient clinic, vaccination for pneumococcus was performed, and recently, powdered pancrelipase (Viokase®, Axcan pharm., Montreal, Canada; lipase 16,800 USP/0.8 gm) was obtained from Canada; she is taking 0.25-0.3 gm (5,000 USP) per meal with a regular diet and multivitamin supplement, and her bowel movements further improved with this treatment.

SDS was described by Bodian et al. for the first time in 1964 (1); however, the report by Shwachman et al. on five cases in pediatric patients with severe pancreatic exocrine insufficiency and bone marrow dysfunction was the first systematic report (2).

The clinical course of SDS is diverse. Common findings include exocrine pancreatic insufficiency, short stature, metaphyseal chondrodysplasia, hematological abnormalities, frequent infection, dental caries, mental retardation, pontine leukoencephalopathy, decreased muscle tone, hepatomegaly and elevated serum aminotransferases, renal tubular dysfunction, ichthyosis in the skin, delayed puberty, diabetes mellitus, myocardial fibrosis, and Hirschsprung's disease.

The essential elements needed to consider the diagnosis are exocrine pancreatic insufficiency and bone marrow dysfunction; short stature, skeletal abnormalities, hepatomegaly, elevation of aminotransferase are used to provide supportive evidence of the diagnosis of SDS. Genetic analysis may be used to confirm the diagnosis, or for prenatal diagnosis or presymptomatic diagnosis within a family as in this case.

Management of a patient with SDS should be multidisciplinary; specialties involved in patient care include pediatric gastroenterologist, hematologist, dentist, dietician, and psychologist. Because a significant percentage of patients suffer from skeletal, dental, and hematological disorders, anticipatory monitoring is advocated. For gastrointestinal manifestations, the mainstay of treatment is pancreatic enzyme therapy, medium-chain triglyceride, and fat-soluble vitamin supplements, together with a normal to increased fat diet. With this treatment, steatorrhea resolves and body weight increases; however, growth is not generally accelerated (3).

An increased risk for developing myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) and acute myeloid leukemia (AML) are the main hematological manifestations (8). The detection of various acquired cytogenetic abnormalities in the bone marrow are markers for a clonal evaluation and often heralds transformation to a more severe form of MDS and/or AML (9). Hence, regular hematological surveillance is required. For the treatment of hematological abnormalities in SDS, stem cell transplantation has been attempted (10); bone marrow transplantation for hematological malignancies in SDS has also been reported (5, 11). However, SDS patients may be more susceptible to transplant-related complications than other transplant patients.

SDS inherits as an autosomal recessive trait (3). The SBDS gene is located on chromosome 7q11. The SBDS gene is composed of 5 exons; it has a 1.6-kb transcript and encode a protein of 250 amino acids, which is a member of highly conserved protein family. Its pseudogene (SBDSP), which has a 90% genetic homology with the SBDS gene, is located in the vicinity and contains critical deletions and nucleotide changes that would render the hypothetical encoded nonfunctional protein.

Genetic analysis in Caucasion patients has revealed two common mutations associated with SDS, those resulting from gene conversion due to recombination between the SBDS and SBDSP genes. The c.258+2T>C mutation results in premature protein truncation due to a change in the splice site (p.84Cfs3) at the second exon; this is the most frequent mutation (6). In this study, genetic analysis of the patient and relatives revealed the c.258+2T>C mutation; the patient was a homozygote for the c.258+2T>C mutations. The patient's father, paternal grandmother, and the patient's mother were heterozygous for the c.258+2T>C mutation. In addition to the c.258+2T>C mutation, the c.183_184TA>CT mutation that results in in-frame stop codon (p.K62X) at position 62 was the second common mutation in a Western study (6).

In our case, the patient's father and paternal grandmother were also heterozygous for the c.183_184TA>CT mutation. This result suggests that the c.183_184TA>CT mutation may also be responsible for SDS in Korea. A recent study from Japan also revealed that the c.258+2T>C mutation and the c.183_184TA>CT mutation were common (12). Therefore, the c.258+2T>C mutation and the c.183_184TA> CT mutation may be the important mutations underlying SDS in Asians, similar to Western reports. The c.201A>G SNP found in the patient's father and paternal grandmother was turned out to be silent polymorphism (6).

With respect to haplotype, the proband had [c.183_184TA>CT; c.201A>G; c.258+2T>C] with wild genomic DNA sequence at 141, and this haplotype was found in one chromosome out of seven patients with SDS in Japan (13). [c.141C> T; c.183_184TA>CT; c.201A>G; c.258+ 2T>C] haplotype was found in two chromosomes out of 15 patients with SDS in Italy (7) and in one chromosome out of seven patients in Japan (13).

A recent Italian study revealed novel mutations for SDS, not resulting from gene conversion events, but rather a missense mutation, nonsense mutation, and frame-shift mutation (7).

The identification of mutations makes it possible for definite diagnosis in presymptomatic patients, including siblings of the proband as in the case reported here, as well as confirmation of the diagnosis when the clinical manifestations are not conclusive. In addition, this information provides the basic knowledge for recurrence risk assessment and genetic counseling for affected families. The relationship between genotype and phenotype has not been established in SDS, yet. Two Italian patients had [c.141C>T; c.183_184TA>CT; c.201A> G; c.258+2T>C]+[c.258+2T>C] genotype; one with anemia, neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, pancreatic insufficiency, metaphyseal dyschondroplasia of the femoral head, narrow chest, and genu valgum, while the other had neutropenia, pancreatic insufficiency, and metaphyseal dyschondroplasia of the femoral head (7). The patient of the present report had a similar genotype except with wild genomic DNA sequence at 141, but she had cyclic neutropenia and pancreatic insufficiency without definite skeletal abnormalities, yet.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 2

Mutations in SBDS causing SDS. (A) Map of SBDS (coding regions in light blue, non-coding regions in dark blue) and sequence alignment of the exon 2 region of SBDS and SBDSP, with genetic-specific (green) and pseudogene-specific (red) sequences indicated. The sequence differences in SBDSP present at position 141, 183, 201, 258+2, 258+124, and 258+126. (B) Electropherogram for direct sequencing from the exon 2 region of SBDS showed sequence changes (arrow) in proband with SDS that was derived from gene mutation (c.258+2T>C homozygous mutation). (C) On direct sequencing analysis of SBDS exon 2 region of the the patient's relatives revealed c.183_184TA>CT mutation and c.201A>G single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) in addition to c.258+2T>C mutation.

Fig. 3

The pedigree of the family is shown with the proband affected with SDS indicated by black symbol. On direct sequencing analysis of SBDS exon 2 region, the proband were shown to be homozygous for the c.258+2T>C mutation and heterozygous for the c.183_184TA> CT mutation and c.201A>G single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP). Her father and paternal grandmother were heterozygous for the c.183_184TA>CT; 258+2T>C mutations and c.201A>G SNP. Her mother was heterozygous for the c.258+2T>C mutation. Her twin brothers, grandfather, and paternal aunt had no mutations in the exon 2 region of the SBDS gene.

Numbers represent sequence of genomic DNA .

Nt, nucleotide.

References

1. Bodian M, Sheldon W, Lightwood R. Congenital hypoplasia of the exocrine pancreas. Acta Paediatr. 1964. 53:282–293.

2. Shwachman H, Diamond LK, Oski FA, Khaw KT. The syndrome of pancreatic insufficiency and bone marrow dysfunction. J Pediatr. 1964. 65:645–663.

3. Aggett PJ, Cavanagh NP, Matthew DJ, Pincott JR, Sutcliffe J, Harries JT. Shwachman's syndrome: a review of 21 cases. Arch Dis Child. 1980. 55:331–347.

4. Kwak JW, Kim S, Lim YT. A case of Shwachman-Diamond syndrome. Korean J Pediatr. 2004. 47:900–903.

5. Park SY, Chae MB, Kwack YG, Lee MH, Kim IH, Kim YS, Kim CS. Allogenic bone marrow transplantation in Shwachman-Diamond syndrome with malignant myeloid transformation: a case report. Korean J Intern Med. 2002. 17:204–206.

6. Boocock GR, Morrison JA, Popovic M, Richards N, Ellis L, Durie PR, Rommens JM. Mutations in SBDS are associated with Shwachman-Diamond syndrome. Nat Genet. 2003. 33:97–101.

7. Nicolis E, Bonizzato A, Assael BM, Cipolli M. Identification of novel mutations in patients with Shwachman-Diamond syndrome. Hum Mutat. 2005. 25:410–417.

8. Woods WG, Roloff JS, Lukens JN, Krivit W. The occurrence of leukemia in patients with the Shwachman syndrome. J Pediatr. 1981. 99:425–428.

10. Vibhakar R, Radhi M, Rumelhart S, Tatman D, Goldman F. Successful unrelated umbilical cord blood transplantation in children with Shwachman-Diamond syndrome. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2005. 36:855–861.

11. Mitsui T, Kawakami T, Sendo D, Katsuura M, Shimizu Y, Hayasaka K. Successful unrelated donor bone marrow transplantation for Shwachman-Diamond syndrome with leukemia. Int J Hematol. 2004. 79:189–192.

12. Kawakami T, Mitsui T, Kanai M, Shirahata E, Sendo D, Kanno M, Noro M, Endoh M, Hama A, Tono C, Ito E, Tsuchiya S, Igarashi Y, Abukawa D, Hayasaka K. Genetic analysis of Shwachman-Diamond syndrome: phenotypic heterogeneity in patients carrying identical SBDS mutations. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2005. 206:253–259.

13. Nakashima E, Mabuchi A, Makita Y, Masuno M, Ohashi H, Nishimura G, Ikegawa S. Novel SBDS mutations caused by gene conversion in Japanese patients with Shwachman-Diamond syndrome. Hum Genet. 2004. 114:345–348.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download