Abstract

We report a case of pituitary apoplexy resulting in right internal carotid artery occlusion accompanied by hemiplegia and lethargy. A 43-yr-old man presented with a sudden onset of severe headache, visual disturbance and left hemiplegia. Investigations revealed a nodular mass, located in the sella and suprasellar portion and accompanied by compression of the optic chiasm. The mass compressed the bilateral cavernous sinuses, resulting in the obliteration of the cavernous portion of the right internal carotid artery. A border zone infarct in the right fronto-parietal region was found. Transsphenoidal tumor decompression following conservative therapy with fluid replacement and steroids was performed. Pathological examination revealed an almost completely infarcted pituitary adenoma. The patient's vision improved immediately after the decompression, and the motor weakness improved to grade IV+ within six months after the operation. Pituitary apoplexy resulting in internal carotid artery occlusion is rare. However, clinicians should be aware of the possibility and the appropriate management of such an occurrence.

Pituitary apoplexy is a well-known clinical syndrome characterized by headache, meningeal irritation, visual loss, ophthalmoplegia, and alterations in consciousness (1). Cerebral infarction associated with pituitary apoplexy is rare. In the present report, we report a rare case of a 43-yr-old man with pituitary apoplexy presenting with hemiplegia.

A 43-yr-old man presented with a sudden onset of severe headache, visual disturbance and left hemiplegia. He was lethargic and unable to walk on his own. The initial neurological examination showed an impaired direct/indirect light reflex of the right eye and a right third nerve palsy, accompanied by anisocoria and ptosis. His motor power was grade II on the left side. Computed tomography (CT) scans of the brain showed an enlarged pituitary fossa containing a hemorrhagic pituitary tumor (Fig. 1A). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a nodular mass, approximately 3×2×3 cm in size, located in the sella and suprasellar portion, accompanied by compression of the optic chiasm (Fig. 1B-D). The mass compressed the bilateral cavernous sinuses, resulting in the obliteration of the cavernous portion of the right internal carotid artery (Fig. 2A). A border zone infarct in the right fronto-parietal region was also found (Fig. 2B).

The patient was initially treated with fluid replacement and steroids. Although the patient's level of consciousness improved during the next 24 hr, the focal neurological signs persisted. Transsphenoidal tumor decompression was performed within four days of symptom onset. The patient's vision improved immediately after the decompression, but the left hemiplegia persisted.

Pathological examination revealed an almost completely infarcted pituitary adenoma (Fig. 3). A conventional cerebral angiography performed one week after the operation and MR angiography demonstrated the restoration of flow within the right internal carotid artery (Fig. 4). His left side motor power improved to grade IV+ within six months after the operation.

The occurrence of cerebral ischemia, or infarct, in patients with pituitary apoplexy is rare, with only 13 cases reported thus far. The ischemic events were attributed to cerebral vasospasm in six cases (2-6) and to mechanical compression by tumor in seven cases (7-13). The pathophysiology of vasospasm following pituitary apoplexy remains unclear. However, several hypotheses have been proposed to account for vasospasm following surgery for pituitary adenoma and other parasellar tumors (14, 15), such as the presence of subarachnoidblood, the release of vasoactive chemical substances from the tumor, hypothalamic damage and dysfunction, and intraoperative manipulation. Bilateral involvement of the intracerebral arteries was common in cases of cerebral vasospasm.

In our case, the restoration of cerebral blood flow following the decompression of the apoplexy was confirmed angiographically. The characteristics of patients whose ischemic events were attributed to the mechanical compression of the cerebral arteries by a pituitary apoplexy are summarized in Table 1. Pituitary apoplexy was associated with both a cerebral angiography and a triple bolus test with the intravenous injection of luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone, thyrotropin-releasing hormone and regular insulin (7, 11). The occlusion sites of the compromised vessels were primarily located in the supraclinoid or cavernous portions of the internal carotid artery. Theoretically, the pressure of the pituitary apoplexy should be stronger than the intraarterial pressure for the mechanical compression. Intrasellar pressure measurements in patients with pituitary apoplexy were conducted in a previous study (16). The measurements ranged from 25-58 mmHg, with a median pressure of 47 mmHg. Moreover, the tight dural attachment of the cavernous and clinoid segments in addition to the surrounding bony structures could create additional pressure and a barrier that occludes the compensatory space of the compromised vessels, resulting in further mechanical compression. Therefore, the primary goal of management is to reduce the intratumoral pressure.

Emergent decompression was performed in two cases (9, 11) of pituitary apoplexy associated with cerebral infarction. The decompression of the internal carotid artery resulted in a patent vessel, but the procedure was also likely to result in the hemorrhagic transformation of the infarct area. The combined effect of the infarct and the brain edema was usually the cause of mortality in patients who underwent emergent decompression. On the other hand, delayed decompression following conservative therapy with steroids was associated with better outcomes in patients with cerebral infarct. We performed delayed surgery following steroid administration in our patient, which resulted in the immediate improvement of the patient's vision. The patient's motor weakness steadily recovered with physiotherapy, and the patient is now capable of walking without assistance.

If the pituitary apoplexy is associated with cerebral ischemia rather than infarct, as in the case described by Bernstein et al. (7), early operative management to restore the flow in the carotid artery may result in the resolution of the neurological deficits. Motor weakness following pituitary apoplexy is rare, but clinicians should pay close attention to the initial images in order to differentiate between infarct and ischemia in cases of pituitary apoplexy.

Figures and Tables

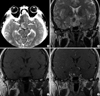

Fig. 1

Computed tomography scan (A) showing a heterogeneous mass of high density in the right side. Coronal magnetic resonance (MR) image showing heterogeneous high-signal intensity on the T2-weighted image (B), slightly elevated signal intensity on the T1-weighted image (C) and focal enhancement with gadolinium (D), suggesting a necrotic or hemorrhagic site.

Fig. 2

Non-visualization of the right internal carotid artery on MRA (A) and linear high signal intensity in the right fronto-parietal region on a diffusion-weighted image (B).

Fig. 3

Microscopic examination showing the infarct region in which viable cells are seen only around the vascular channels (H&E, ×100 [A] and ×200 [B]).

References

1. Dubuisson AS, Beckers A, Stevenaert A. Classical pituitary tumour apoplexy: clinical features, management and outcomes in a series of 24 patients. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2007. 109:63–70.

2. Akutsu H, Noguchi S, Tsunoda T, Sasaki M, Matsumura A. Cerebral infarction following pituitary apoplexy-case report. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 2004. 44:479–483.

4. D'Haens J, Baleriaux D, Mockel J, Flamment-Durand J, Brotchi J. Ischemic pituitary apoplexy and cerebrovascular accident. Neurochirurgie. 1983. 29:401–405.

5. Itoyama Y, Goto S, Miura M, Kuratsu J, Ushio Y, Matsumoto T. Intracranial arterial vasospasm associated with pituitary apoplexy after head trauma-case report. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 1990. 30:350–353.

6. Pozzati E, Frank G, Nasi MT, Giuliani G. Pituitary apoplexy, bilateral carotid vasospasm, and cerebral infarction in a 15-year-old boy. Neurosurgery. 1987. 20:56–59.

7. Bernstein M, Hegele RA, Gentili F, Brothers M, Holgate R, Sturtridge WC, Deck J. Pituitary apoplexy associated with a triple bolus test. Case report. J Neurosurg. 1984. 61:586–590.

8. Clark JD, Freer CE, Wheatley T. Pituitary apoplexy: an unusual cause of stroke. Clin Radiol. 1987. 38:75–77.

9. Lath R, Rajshekhar V. Massive cerebral infarction as a feature of pituitary apoplexy. Neurol India. 2001. 49:191–193.

10. Majchrzak H, Wencel T, Dragan T, Bialas J. Acute hemorrhage into pituitary adenoma with SAH and anterior cerebral artery occlusion. Case report. J Neurosurg. 1983. 58:771–773.

11. Rosenbaum TJ, Houser OW, Laws ER. Pituitary apoplexy producing internal carotid artery occlusion. Case report. J Neurosurg. 1977. 47:599–604.

12. Sakalas R, David RB, Vines FS, Becker DP. Pituitary apoplexy in a child. Case report. J Neurosurg. 1973. 39:519–522.

13. Schnitker MT, Lehnert HB. Apoplexy in a pituitary chromophobe adenoma producing the syndrome of middle cerebral artery thrombosis; case report. J Neurosurg. 1952. 9:210–213.

14. Aoki N, Origitano TC, al-Mefty O. Vasospasm after resection of skull base tumors. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1995. 132:53–58.

15. Hyde-Rowan MD, Roessmann U, Brodkey JS. Vasospasm following transsphenoidal tumor removal associated with arterial change of oral contraception. Surg Neurol. 1983. 20:120–124.

16. Zayour DH, Selman WR, Arafah BM. Extreme elevation of intrasellar pressure in patients with pituitary apoplexy: relation to pituitary function. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004. 89:5649–5654.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download