Abstract

We report a case of fatal fungal peripheral suppurative thrombophlebitis, caused by Candida albicans, which was disseminated to the blood, lungs, eyes, and spine. Clinical suspicion and aggressive management are important in managing fungal peripheral suppurative thrombophlebitis. Early clinical suspicion is important in managing fungal peripheral suppurative thrombophlebitis, and radical excision of the affected veins, recognition of metastatic foci, and use of systemic antifungal agents are essential to avoid septic shock and death.

Use of intravenous catheters for fluid infusion therapy and hemodynamic monitoring is sometimes complicated by catheter-related infection. While most cases are resolved by catheter removal and treatment with antibiotics, serious complications can occur, including suppurative thrombophlebitis, infective endocarditis, and metastatic infection (1). In addition, thrombophlebitis is a common cause of postoperative fever.

The commonly isolated organisms are normal skin flora, such as Staphylococcus epidermidis and Staphylococcus aureus, followed by Gram-negative rods (1). The incidence of fungal infection, particularly with Candida species, is very low. In recent decades, however, there has been a dramatic increase in Candida infection in critically ill patients (2). Here we present an unusual case of peripheral suppurative thrombophlebitis due to Candida albicans, in which the infection was disseminated to the blood, lungs, eyes, and spine.

A 49-yr-old man diagnosed with rectal cancer underwent a low anterior resection. An ileostomy was performed on the seventh postoperative day due to an anastomotic leakage. Four days after the ileostomy, the patient developed a high fever, with his axillary temperature remaining at 40.2℃ for 2 days. Upon transfer to the intensive care unit (ICU), the patient was mentally alert but had a febrile sensation. His temperature was 39.4℃, his pulse was 125 beats/min and regular, his blood pressure was 145/80 mmHg, and his respiratory rate was 33 breaths/min. Physical examination showed basilar rales and erythema over the left antecubital vein, through which fluids and antibiotics had been administered previously. There was no evidence of pharyngeal injection or neck stiffness. His abdomen was mildly distended but there was no tenderness or rebound tenderness and no abnormalities of the surgical drains or of the ileostomy. Laboratory parameters included a leukocyte count of 7,700 cells/µL and a C-reactive protein level of 7.86 mg/dL. A chest roentgenogram revealed segmental atelectasis in the right lower lobe. Abdomino-pelvic computed tomography showed a small amount of fluid collection around the anastomotic site.

The fever was thought to be due to atelectasis, intraabdominal fluid collection, and thrombophlebitis. Ceftizoxime (1 g/8 hr) and metronidazole (500 mg/8 hr), which had been administered postoperatively, were discontinued on the fifth postoperative day. Starting on the eighth postoperative day, the patient was treated with intravenous vancomycin (500 mg/6 hr) and meropenem (500 mg/6 hr) for 4 days. To rule out suppurative thrombophlebitis, aspiration of the area of erythema on the left arm was attempted using a 21-gauge needle. However, it failed to yield any aspirate. His temperature continued to increase, to 40.5℃. On the third ICU day, he developed bilateral, patchy, pulmonary consolidation, and pulmonary edema, suggesting septic pneumonia rather than primary pneumonia. The patient was then intubated and given positive-pressure mechanical ventilation. Since there was no clinical improvement of the left arm erythema after the removal of the peripheral catheter, the phlebitic vein was explored. Purulent material and thrombus were found, and a 20 cm segment of the involved vein was excised up to where the vessel appeared normal.

Blood culture obtained on the ICU admission day revealed C. albicans. Candida was also grown from the excised vessel, and the antibiotic regimen was modified to include amphotericin B 1 mg/kg for 3 weeks. There were no signs of nephrotoxicity after starting amphotericin treatment. We performed fundoscopy, transthoracic echocardiography, and transesophageal echocardiography to examine the metastatic foci of the candida. Fundoscopy revealed multiple raised, white, fluffy, cottonball-like chorioretinal lesions, indicative of endophthalmitis (Fig. 1). The echocardiogram showed no evidence of metastatic infection.

After phlebectomy, the patient rapidly effervesced and all signs of inflammation resolved. The pneumonia and pulmonary edema also resolved. However, on the tenth ICU day, we found another, previously unsuspected peripheral thrombophlebitis lesion on the right antecubital vein. Exploration of this lesion showed that it was also a fungal peripheral thrombophlebitis with pus and thrombus. On the eleventh ICU day, he was extubated and transferred to a general ward.

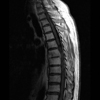

The patient was discharged after one month in hospital. Shortly after discharge, the patient experienced severe back pain with no sign of infection. A radiograph and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the thoraco-lumbar region displayed diffuse hypointensity of the T7 and T8 vertebrae (Fig. 2). This finding was highly suggestive of bone metastasis secondary to colon cancer. He received up to 4,000 cGy radiation therapy for 20 days, but his back pain was not relieved. An open biopsy of the tumor-like mass in the spine showed no evidence of tumor, but tissue culture revealed C. albicans. This finding corresponded to fungal spondylitis. After administering amphotericin B 1 mg/kg for 6 weeks, the patient's back pain resolved and he was discharged from the hospital. Following discharge, he was prescribed 400 mg/day oral fluconazole for 2 months.

Suppurative thrombophlebitis is a serious postoperative infectious complication that develops in 7% of patients with intravenous catheter infections and can lead to a significant morbidity and, if untreated, death (1). The pathogenesis of suppurative thrombophlebitis is believed to be related to endothelial trauma, invasion of skin-colonizing organisms via an indwelling cannula, or inadequate local skin care in patients cannulated for longer than 48 hr (3, 4).

Risk factors for the development of candidal thrombophlebitis are similar to those reported for nosocomial candidal infections: current use of multiple antibiotics, prior treatment with multiple antibiotics, use of total parenteral nutrition, ICU admission, previous abdominal surgery, steroid use, and an immunocompromised state. Overgrowth of Candida in the gastrointestinal tract resulting from long-term antimicrobial therapy may seed the intravenous device (3). Thus, in patients with the above risk factors, there should be a high index of suspicion of serious Candida-related complications.

In contrast to bacterial suppurative thrombophlebitis, fungal thrombophlebitis is unimpressive in appearance, and thus is often not discovered until specifically investigated. Unfortunately, this usually only occurs after the recognition of fungemia, shock, or organ failure (5-7). Our patient had an anastomotic leakage and had prior and current treatment with multiple antibiotics (prophylactic antibiotics for 5 days and empiric antibiotics for 4 days) through an intravenous catheter. Surgical patients, especially those with intraabdominal infection, who are critically ill while being treated with long-term antimicrobial therapy should be suspected of fungal infection.

In addition to suppurative thrombophlebitis, infectious foci metastatic to other visceral organs may develop in patients with candidal infections associated with intravenous catheters. Endophthalmitis is a relatively high metastatic infection that can be present in up to 20% of patients with fungal septicemia associated with suppurative thrombophlebitis. Once candidemia has occurred, choroidal lesions may develop, followed by retinal lesions. Ophthalmoscopic examination can detect fungal endophthalmitis at an early stage, as well as monitor the progress of candidemia, the development of lesions and systemic involvement. The infection can spread to other visceral organs, resulting in pneumonia, septic arthritis, meningitis, and infective spondylitis. As with endophthalmitis, metastatic infection to other organs should be followed up to determine the prognosis and monitor the response to treatment (8). The duration of antifungal treatment should be adjusted according to the symptoms and signs of suppurative thrombophlebitis and metastatic foci (9).

Radical excision of the affected vein, along with treatment with an antifungal agent, is the treatment of choice for patients with peripheral candidal suppurative thrombophlebitis (1). In this case, despite the excision of the affected veins and systemic antifungal treatment, undetected metastatic spondylitis was aggravated and caused a systemic infection. MRI can assess the presence and degree of many spinal disorders and can differentiate between infections and neoplasms in the spine. In some cases, however, atypical spondylitis, including fungal infection, tuberculous spondylitis and hematogenous epidural abscesses, does not show the classical pattern (10). In our patient, MRI could not reliably differentiate between a spinal tumor and spinal infection. Patients with a history of systemic fungemia should be suspected of having a metastatic infection.

In patients who develop fungemia after placement of postoperative peripheral indwelling catheters, it is imperative to rule out peripheral thrombophlebitis as a focus of fungal infection. Peripheral thrombophlebitis may cause lethal complications such as persistent bacteremia, shock, and metastatic infection.

Once properly diagnosed, patients should be treated with early radical excision of affected veins, recognition of other metastatic foci, and use of antifungal agents, thus improving their prognosis.

Figures and Tables

References

1. Arnow PM, Quimosing EM, Beach M. Consequences of intravascular catheter sepsis. Clin Infect Dis. 1993. 16:778–784.

2. Deitch EA, Marini JJ, Huseby JS. Suppurative Candida phlebitis of a peripheral vein. J Trauma. 1980. 20:618–620.

3. Torres-Rojas JR, Stratton CW, Sanders CV, Horsman TA, Hawley HB, Dascomb HE, Vial LJ. Candidal suppurative peripheral thrombophlebitis. Ann Intern Med. 1982. 96:431–435.

4. Hauser CJ, Bosco P, Davenport M, Davenport M, Ehrensaft D, Latif M, McNamara BT. Surgical management of fungal peripheral thrombophlebitis. Surgery. 1989. 105:510–514.

5. Yackee JM, Topiel MS, Simon GL. Septic phlebitis caused by Candida albicans and diagnosed by needle aspiration. South Med J. 1985. 78:1262–1263.

6. Murray CK, Beckius ML, McAllister K. Fusarium proliferatum superficial suppurative thrombophlebitis. Mil Med. 2003. 168:426–427.

7. Benoit D, Decruyenaere J, Vandewoude K, Benoit D, Roosens C, Hoste E, Poelaert J, Vermassen F, Colardyn F. Management of candidal thrombophlebitis of the central veins: case report and review. Clin Infect Dis. 1998. 26:393–397.

8. Omuta J, Uchida K, Yamaguchi H, Shibuya K. Histopathological study on experimental endophthalmitis induced by bloodstream infection with Candida albicans. Jpn J Infect Dis. 2007. 60:33–39.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download