Abstract

Dermatomyositis (DM) is an uncommon inflammatory myopathy with characteristic rash accompanying, or more often preceding, muscle weakness. There is a well-recognized association between DM and several cancers, such as ovarian cancer, breast cancer, melanoma, colon cancer, and non-Hodgkin lymphoma. We report the first case of cancer of unknown primary site associated with DM. A 62-yr-old woman presented to us with both shoulder painful swelling and facial edema. She was diagnosed previously as cancer of unknown primary site, histologically confirmed with squamous cell carcinoma in a pelvic mass. For the following days, she complained of erythematous face followed by progressive weakness of the proximal muscles of upper and lower limbs. The laboratory tests showed an increased muscle enzyme and acute phase reactants. The electromyogram showed the typical findings of DM. After the treatment with high dose steroid and methotrexate, the proximal motor weakness improved, and she received palliative radiation therapy.

Dermatomyositis (DM) is an idiopathic inflammatory myopathy with characteristic cutaneous manifestations (1). It is strongly associated with malignancy, which is diagnosed in about 25% of DM patients above the age of 50. Malignant disease may occur before the onset of myositis, concurrently, or afterward. The most commonly observed cancers in patients with DM are breast and gynecological cancers among women, lung cancer among men, and gastrointestinal malignancies in both sexes (2, 3).

A small number of cancers first appear in one or more metastatic sites, and the primary site is not known despite full evaluation. So it is called cancer of unknown primary site (CUPS). CUPS is present in 5-10 percent of all malignancies.

Although many malignancies are associated with DM, CUPS has not been reported to be associated with DM to the best of our knowledge. We report here on the first case of CUPS associated with DM.

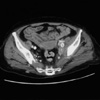

A 62-yr-old woman visited our hospital and presented to us with hip pain. She was a nonsmoker, not addicted to alcohol, and she had no significant past gynecological or family history. Physical examination showed painful tenderness and swelling on the left gluteal lesion along the lower extremities. Laboratory findings revealed no significant abnormalities including tumor markers, such as CA-125, CEA. Chest radiogragh showed no mass-like lesion or infiltration. A computed tomographic scan of the pelvis revealed a large lobulated mass in left iliopsoas muscle (Fig. 1). Multiple lymphadenophathies were shown in the paraaortic and left common iliac chain. For confirmative diagnosis, she received biopsy on the iliopsoas mass. The tissue showed metastatic, well differentiated squamous cell carcinoma. For the evaluation of the primary site, she received chest computed tomography, esophagogastroscopy, anoscopy, gynecologic examination, and positron emission tomography. These intensive workup revealed no specific findings except for positron emission tomography, which revealed hypermetabolic lesions in the iliopsoas muscle with regional lymph nodes. However, the primary site was not identified. We concluded the diagnosis as CUPS and planned to perform palliative chemoradiotherapy for the iliopsoas mass. However, her general condition was poor, with a Easten Co-operative Oncology Group (ECOG) score of 3, so she just received opioid for pain management at an outpatient clinic.

Two weeks after diagnosis, she was admitted to hospital because of facial edema, shoulder pain, dysphagia, and progressive weakness of the proximal muscles of her upper and lower limbs. Her performance status score was ECOG 4 due to pain and weakenss. Physical examination showed the heliotropic discoloration of the eyelids with periorbital edema, red, violaceous, nonpurpuric skin rash (Gottron's sign) on the interpharyngeal joints, face, neck, anterior chest, and arms (Fig. 2).

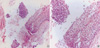

The characteristic clinical pictures of DM were supported by several laboratory abnormalities: increases in creatine kinase of 5,835 U/L (normal range, 30-225), serum myoglobin of 681 ng/mL (normal range, 0-65), serum lactate dehydrogenase of 639 U/L (normal range, 100-220), and erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 66 mm/hr (normal range, 0-20). Antinuclear antibodies, anti-Jo-1 antibody, anti-RNP antibody, anti-Ro antibody, and anti-La antibody were negative. These data could rule out primary autoimmune disease. To exclude skin metastasis, she received biopsy from the violaceous skin for histologic examination, which demonstrated pericapillary inflammation. Electromyographic examination revealed myopathic and neurologic abnormalities (fibrillations, polyphasic motor unit potentials of low amplitude, and short duration) compatible with myositis. The diagnosis was confirmed as DM based on the typical skin rash, proximal muscles weakness, elevated levels of serum muscle enzymes, and electromyogram showing a myopathic pattern. She was treated with 60 mg/day of prednisone intravenously immediately after diagnosis. She showed the improvement in skin lesions and muscle weakness as well as reduction of muscle enzyme. After treatment with prednisone (60 mg/day) for 2 weeks, she received additional methotrexate (7.5 mg/week) and steroid at a tapered dose and she showed improvement in the swallowing and muscular weakness of lower limbs. Four weeks after the initiation of treatment, she could start radiation therapy at an out-patient clinic and showed relatively good general condition, with a score of ECOG 2. Restaging workup after radiation therapy (total 7,000 cGy) showed nearly complete response. Currently, she has received low dose steroid (7.5 mg/day) and methotrexate (7.5 mg/week), and we are planning palliative chemotherapy (Fig. 3).

The association between malignancy and DM has revealed that the cancer rate in DM was five to seven times higher than that of the general population (4). Kim et al. already reported about 10% of dermatomyositis/polymyositis patients associated with malignancy (5).

Cancer can be diagnosed before, at the time when the cancer first becomes obvious, or after the diagnosis of myositis with a peak incidence occurring within the two-year period before and after the development of myositis (6, 7). The highest risk for developing subsequent tumors is within a short period after diagnosis of DM (8). The etiology of DM in patients with cancer is poorly understood. Proposed mechanisms include: common environmental factors such as virus, a drug, or a chemical, triggering both cancer, and myositis in a genetically predisposed host, an immune complex or cellular immune reaction involving tumor antigens cross-reacting with both muscle and skin antigens, tumor myotoxin or other products causing muscle and skin inflammation, and both the tumor and myositis resulting from a subtle host abnormality of humoral and cellular immunity (9, 10). In this case, CUPS preceded the development of DM, and this temporal relation suggests a paraneoplastic syndrome. It has been noted that DM improves after the treatment of cancer, with muscle weakness resuming at the relapse of the malignant disease.

The management of malignancy-associated DM includes steroids and/or azathioprine as an alternative and steroid-sparing agent. However, DM associated with cancer is generally more resistant to corticosteroid and cytotoxic therapies compared to idiopathic myositis. The activity of DM can reflect the state of the underlying malignancy. Effective antitumor treatment may be accompanied by regression of the inflammation, and conversely, it may deteriorate with progressive malignant disease (11).

A wide variety of cancers have been reported in patients with DM. Compared with the general population, lung, breast, colon, pancreas, and gynecologic tumors were more common in DM (12-15). Especially, women constitute two-thirds of DM patients with malignancy, and most of the malignancies were of the female genital tract with epithelial ovarian carcinoma predominating (16). In consideration of histologic subtypes of dermatomyositis associated with cancer, Hill et al. reported that adenocarnicoma was the most common histologic subtype (3).

To our knowledge, the association between DM and CUPS has not been reported previously. In this case, the first manifestation of proximal muscle weakness was overlooked as general weakness associated with cancer progression. However, typical skin rash and elevated muscle enzyme were the clue to the diagnosis. The improvement of performance status after treatment of DM enabled complete radiation therapy and the better clinical outcome.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 1Abdominopelvic CT showed a large lobulated mass with speckled calcification in left iliopsoas muscle. |

References

2. Zantos D, Zhang Y, Felson D. The overall and temporal association of cancer with polymyositis and dermatomyositis. J Rheumatol. 1994. 21:1855–1859.

3. Hill CL, Zhang Y, Sigurgeirsson B, Pukkala E, Mellemkjaer L, Airio A, Evans SR, Felson DT. Frequency of specific cancer types in dermatomyositis and polymyositis: a population-based study. Lancet. 2001. 357:96–100.

4. Ponyi A, Constantin T, Garami M, Andras C, Tallai B, Vancsa A, Gergely L, Danko K. Cancer-associated myositis: clinical features and prognostic signs. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2005. 1051:64–71.

5. Kim SM, Choi YH, Oh MD, Nam TS, Chung MH, Pai HJ, Song YW, Choe KW. A clinical analysis of 100 patients with dermatomyositis-polymyositis. Korean J Med. 1990. 39:812–822.

6. Lakhanpal S, Bunch TW, Ilstrup DM, Melton LJ 3rd. Polymyositis-dermatomyositis and malignant lesions: Does an association exist? Mayo Clin Proc. 1986. 61:645–653.

7. Sigurgeirsson B, Lindelöf B, Edhag O, Allander E. Risk of cancer in patients with dermatomyositis or polymyositis. A population-based study. N Engl J Med. 1992. 326:363–367.

8. Wakata N, Kurihara T, Saito E, Kinoshita M. Polymyositis and dermatomyositis associated with malignancy: a 30-year retrospective study. Int J Dermatol. 2002. 41:729–734.

9. Buchbinder R, Hill CL. Malignancy in patients with inflammatory myopathy. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2002. 4:415–426.

10. Andras C, Ponyi A, Constantin T, Csiki Z, Illes A, Szegedi G, Danko K. Myositis associated with tumors. Magy Onkol. 2002. 46:253–259.

11. Carsons S. The association of malignancy with rheumatic and connective tissue diseases. Semin Oncol. 1997. 24:360–372.

12. Whitmore SE, Rosenshein NB, Provost TT. Ovarian cancer in patients with dermatomyositis. Medicine (Baltimore). 1994. 73:153–160.

13. Eum EA, Choi SW, Min YJ, Koh SH, Suh HS, Suh JH. A case of pancreatic cancer presenting as dermatomyositis. J Korean Geriatr Soc. 2006. 10:43–46.

14. Park EJ, Ryu JH, Kim KH, Kim KJ. A case of dermatomyositis associated with nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Korean J Dermatol. 2004. 42:1069–1072.

15. Hyun DH, Song JS, Lee MH, Lee SY, Kim YS, Kim IH, Park W, Kim CS. A case of breast cancer recurrence presenting as dermatomyositis. J Korean Rheum Assoc. 2003. 10:451–455.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download