Abstract

The extravasation of chyle into the peritoneal space usually does not accompany an abrupt onset of abdominal pain with symptoms and signs of peritonitis. The rarity of this condition fails to reach preoperative diagnosis prior to laparotomy. Here, we introduce a case of chylous ascites that presented with acute abdominal pain mimicking peritonitis caused by ovarian torsion in a 41-yr-old female patient with advanced gastric carcinoma. An emergency exploratory laparotomy was performed but revealed no evidence of ovarian torsion. Only chylous ascites was discovered in the operative field. She underwent a complete abdominal hysterectomy and salphingo-oophorectomy. Only saline irrigation and suction-up were performed for the chylous ascites. The postoperative course was uneventful. Her bowel movement was restored within 1 week. She was allowed only a fat-free diet, and no evidence of re-occurrence of ascites was noted on clinical observation. She now remains under consideration for additional chemotherapy.

Chronic chylous ascites, associated with malignant obstructions in the lymphatic channel, does not usually cause acute abdominal pain. That is, chyle extravasation into the peritoneal cavity is rarely associated with the sudden development of peritonitis (1). The rarity of this condition can lead to a missed preoperative diagnosis.

We present a case of acute chylous peritonitis in a patient with advanced gastric carcinoma who presented with signs and symptoms of peritonitis caused by ovarian torsion.

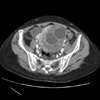

The Department of Surgery was consulted for the finding of milky peritoneal fluid in a 41-yr-old female undergoing a complete abdominal hysterectomy with bilateral salphingo-oophorectomy (TAH-BSO) by a gynecologist at our institution. The patient had been admitted to the Yonsei University Medical Center, Seoul, Korea, for chemotherapy due to advanced gastric carcinoma. A previous computed tomography (CT) scan had shown bilateral metastatic ovarian tumors. During her stay, the patient suddenly developed acute abdominal pain. A physical examination revealed direct tenderness to palpation, rebound tenderness, and guarding; she was also noted to have a palpable left supraclavicular node. A chest radiography was normal; an emergent abdominal pelvic CT scan showed increased bilateral ovarian tumors with minimal intraperitoneal fluid collection (Fig. 1). Her vital signs were stable, and the patient was afebrile. The initial blood laboratory results showed a total leukocyte count of 3,600/µL with 58% neutrophils, Hb 12.8 g/dL, platelet count 245,000/µL, Na 143 mM/L, K 3.9 mM/L, Cl 103 mM/L, BUN 13.6 mg/dL, creatinine 0.9 mg/dL, glucose 116 mg/dL, AST 20 IU/L, ALT 14 IU/L, and total bilirubin 0.6 mg/dL. Based on the physical examination and CT findings, peritonitis caused by ovarian torsion was strongly suspected, leading a gynecologist to perform an exploratory laparotomy on an emergency basis. In the operative field, no ovarian vascular compromise or torsion was found. However, a minimal to moderate amount of milky peritoneal fluid was observed in the pelvic cavity and along the right paracolic gutter.

After the TAH-BSO, the patient was evaluated at the Department of Surgery for chylous ascites. On intraperitoneal exploration, the stomach seemed to be tethered to the pancreas, but there was no evidence of peritoneal carcinomatosis. Diffuse lymphatic ectasia and milky fluid discharge were noted around the small bowel mesentery (Fig. 2) and ascending colon (Fig. 3). Only saline irrigation and suction were performed without external drainage. The patient recovered uneventfull and restored bowel movement on the 5th postoperative day. She was given a fat-free diet, and no evidence of reoccurrence of ascites was noted on clinical observation, such as the measurement of daily body weight and abdominal circumference. The patient now remains under consideration for additional chemotherapy.

Chylous ascites is due to the disruption of the lymphatic system. Chylous ascites is an uncommon finding, with an incidence of 1 in 20,000 hospital admissions (2). Paracentesis is the most important diagnostic modality and reveals milky peritoneal fluid with a triglyceride concentration 2 to 8 times that of plasma (3). Malignant lymphoma is the most common cause of chylous ascites and accounts for 50% of cancer-related cases (4). Malignant invasion causes lymphatic channel fibrosis and disruption of the peritoneal cavity lymphatic system, enhancing extravasation distal to the obstruction. Other malignancies such as colon, pancreatic, stomach, ovarian cancers, and intestinal carcinoid, Kaposi sarcoma, and lymphangiomyomatosis (5) can also cause chylous ascites. Other etiologies include infectious diseases, such as peritoneal tuberculosis and lymphatic filariasis, lymphatic system congenital anomalies, radiation side effects, abdominal surgery complications, and portal hypertension from liver cirrhosis (6).

Chronic chylous ascites usually does not present with acute abdominal pain, as mentioned previously. In the present case, the abrupt onset was accompanied by peritoneal signs that led to an emergency exploratory laparotomy due to a concern of ovarian torsion caused by large bilateral ovarian Krukenburg's tumors. Strictly speaking, the operative finding did not show any evidence of acute inflammatory changes in the patient's peritoneal cavity; however, clinical symptoms definitively suggested peritonitis, requiring immediate surgical intervention. Therefore, the diagnosis of acute chylous peritonitis may be more appropriate than that of chylous ascites, depending on the clinical setting.

Although there was no gross lymphadenopathy or peritoneal cancer seeding, microscopic metastasis in the small lymphatic system was suspected as the etiology. Later it was revealed that the patient had left supraclavicular engorgement, which subsequently decreased after the laparotomy. This might explain the pathophysiologic mechanism of her acute chylous ascites. Disruption of the abdominal cavity peripheral lymphatic system, caused by thoracic duct obstruction from a metastatic left clavicular lymph node, resulted in sudden extravasation and acute chylous peritonitis. In our hypothesis, if it had not been for the chylous ascites, the abrupt onset of chylothorax might have occurred, and would have presented with dyspnea as the initial symptom.

The optimal management of chylous ascites includes a protein-rich, low-fat diet, medium-chain triglycerides, Sandostatin, and Orlistat (Xenical) (7-10). Total parenteral nutrition can be used to decrease lymphatic flow and to promote lymphatic disruption closure. Fortunately, our patient was well managed with dietary fat restriction. Although no drain catheters were placed, there was no evidence of further peritoneal fluid collection.

In this case, the symptoms and signs of peritonitis were present; however, there was no accompanying fever, leukocytosis, or intraperitoneal free air. Although spontaneous acute chylous peritonitis is rare, the disease should be considered in a patient with underlying malignant disease and signs of peritoneal irritation without associated leukocytosis, fever, and intraperitoneal free air. In these cases, diagnostic laparoscopy should be emphasized (11). In our patient, laparoscopy prior to laparotomy would have confirmed chylous ascites and resulted in a less invasive surgical procedure.

Figures and Tables

References

1. Thompson PA, Halpern NB, Aldrete JS. Acute chylous peritonitis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1981. 3:Suppl 1. 51–55.

2. Press OW, Press NO, Kaufman SD. Evaluation and management of chylous ascites. Ann Intern Med. 1982. 96:358–364.

5. Kim HS, Park MI, Suh KS. Lymphangiomyomatosis arising in the pelvic cavity: a case report. J Korean Med Sci. 2005. 20:904–907.

6. Fang FC, Hsu SD, Chen CW, Chen TW. Spontaneous chylous peritonitis mimicking acute appendicitis: a case report and review of literature. World J Gastroenterol. 2006. 12:154–156.

7. Hashim SA, Roholt HB, Babayan VK, Vanitallie TB. Treatment of chyluria and chylothorax with medium chain triglyceride. N Engl J Med. 1964. 270:756–761.

8. Demos NJ, Kozel J, Scerbo JE. Somatostatin in the treatment of chylothorax. Chest. 2001. 119:964–966.

9. Chen J, Lin RK, Hassanein T. Use of Orlistat (Xenical) to treat chylous ascites. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2005. 39:831–833.

10. Ji HS, Ryu MH, Hur JR, Choi JM, Chang HM, Kim TW, Lee JS, Kim WK, Kang YK. A case of chylous ascites associated with non-Hodgkin's lymphoma and liver cirrhosis. Korean J Hematol. 2002. 37:236–240.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download