Abstract

Synovial sarcoma is a rare but distinct soft tissue neoplasm, most commonly occurring in para-articular regions of the extremities of young adults and also occurring in the head and neck region. To the best of our knowledge, only one case of primary synovial sarcoma of the thyroid has been previously reported. Here, we report a 15-yr-old man who had a chief complaint of a palpable neck mass. The neck computed tomography revealed a relatively well-demarcated solid mass in the left thyroid gland. After fine needle aspiration cytology, total thyroidectomy and lymph node dissection were performed. Grossly, the mass was covered by the same capsule as the thyroid gland, measuring 6×5×5 cm in dimensions and weighing 78 gm. The cut surface showed a well demarcated, lobulated, grayish tan, and rubbery solid tumor. Histologically, this tumor was a biphasic synovial sarcoma. Immunohistochemical, ultrastructural, genetic studies, and cytologic findings were all consistent with synovial sarcoma. When synovial sarcomas arise in this unusual site, recognition and differential diagnosis become more difficult. The differential diagnosis of a spindle epithelial tumor with thymus-like differentiation is very difficult due to their similar clinical, histological, and immunohistochemical features. Ultrastructural and cytogenetic studies for synovial sarcoma are necessary to establish a definitive diagnosis.

Synovial sarcoma is a relatively common and well defined soft tissue sarcoma, accounting for about 5% to 10% of all soft tissue sarcomas (1). The mean age at the time of diagnosis is about 30 yr (1). About 70% of cases occur in patients older than 20 yr old, but the remaining 30% of cases are diagnosed between ages 1 and 20 yr (median, 13 yr) (2). Approximately 85% of this tumor occur in para-articular regions of the extremities, with a predilection to the lower extremities. Following the extremities, the tumors arise in the head, neck, and trunk (1). Synovial sarcoma has also been described at various anatomic sites including the skin, heart, lung, pleura, prostate, kidney, central nervous system, bone, esophagus, liver, ovary, vulva, peripheral nerve, and mediastinum (1, 3-6). To the best of our knowledge, only one case of primary synovial sarcoma that originated in the thyroid gland has been reported (7). Synovial sarcoma of the head and neck region account for about 10% of all cases (1). When synovial sarcomas arise in these unusual sites, recognition and differential diagnosis becomes more difficult. Here, we report a primary synovial sarcoma of the thyroid gland with clinical, cytologic, histopathological, immunohistochemical, ultrastructural, and molecular genetic features, and discuss the differential diagnosis between synovial sarcoma and other primary thyroid tumors.

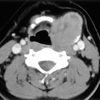

A 15-yr-old man had a chief complaint of a palpable neck mass for 4 months. He had no family or past medical history. The patient first recognized the neck mass 4 months before, and it rapidly increased in size during the latter 2 months. All laboratory tests, including thyroid function tests, were unremarkable. The neck computed tomography revealed a relatively well-demarcated solid mass at the superior and lateral portion of the left thyroid gland (Fig. 1), suggesting that this lesion may be either a primary thyroid mass with exophytic growth or a soft tissue tumor pushing the thyroid, in particular, a neurogenic tumor. The fine needle aspiration cytology disclosed moderate cellularity with a predominance of bipolar spindle-shaped cells having oval- to spindle-shaped nuclei and finely granular chromatin without nucleoli. The plump spindle cells in the clusters were arranged in a fascicular or streaming pattern with a mild degree of pleomorphism. The cytoplasm of the spindle and oval cells was moderate and pale eosinophilic. These cytologic findings were initially regarded as a benign follicular lesion and could not lead to a definitive diagnosis (Fig. 2).

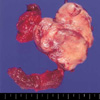

The patient subsequently underwent total thyroidectomy and left cervical lymph node dissection. The mass was encapsulated and covered by the same capsule as the thyroid, measuring 6×5×5 cm in dimensions. The cut surface showed a well-demarcated, lobulated and grayish tan solid mass with rubbery consistency (Fig. 3).

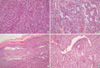

Microscopically, the tumor was separated from the thyroid parenchyme by a thick fibrous capsule and showed a biphasic growth pattern, which was an admixture of spindle and epithelial cell components in almost equal proportions (Fig. 4A). The spindle cell component consisted of fascicles of atypical fibroblast-like spindle cells, and the epithelial component was composed of solid nests of plump epithelioid cells with well-formed glandular structures (Fig. 4B). The periphery of the tumor showed focal calcification and more densely packed spindle cells without an epithelial component (Fig. 4C). Focal areas of hemangiopericytic pattern were also present (Fig. 4D). The glandular structures were lined by round or cuboidal cells with round to oval nuclei and abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm. Some glandular lumens are filled with pale basophilic materials, which were periodic acid schiff and alcian blue positive. The intervening spindle cells were slightly plump and had elongated, vesicular nuclei with a scant amount of eosinophilic cytoplasm. On average, 15 mitotic figures were seen per 10 high-power fields both in epithelial and spindle cells.

On immunohistochemical staining, the glandular elements were diffusely and strongly stained with cytokeratin, whereas the spindle cells were diffusely stained with vimentin and focally with epithelial membrane antigen (Fig. 5). The tumor cells were diffusely positive for CD99. Stains for muscle specific actin, smooth muscle actin, S-100, carcinoembryonic antigen, synaptophysin, chromogranin, thyroglobulin, and thyroid transcription factor-1 (TTF-1) were all negative in the tumor cells.

On ultrastructural examination, the tumor was composed of solid nests of epithelial cells and fascicles of spindle cells, which were partially covered by basal lamina. The epithelial cells had desmosome-like cell junctions, whereas the spindle cells had no cell junctions. No tonofilaments, granules, microvilli, or other specific organelles were found (Fig. 6).

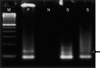

The SYT-SSX fusion gene transcript was identified in the paraffin-embedded tumor tissue using the reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction method (Fig. 7).

A synovial sarcoma is a distinctive soft tissue sarcoma and their immunohistochemical and cytogenetic features are well described (1). While most tumors are located in the vicinity of large joints and intimately related to tendons, tendon sheaths and bursal structures, they rarely occur within the joint cavity itself (1). Furthermore, true synovial lining cells are not stained with epithelial cell markers, such as cytokeratin and epithelial membrane antigen, but this tumor is stained with these markers (8). Also, a synovial sarcoma occurs in various locations that are unrelated to joint structures (1, 3-6). These findings suggest that synovial sarcoma is not related to normal synovium and may be derived from pleuripotential mesenchymal cells, capable of partial or aberrant epithelial differentiation (9). From this point of view, it is possible that a primary synovial sarcoma can occur in the thyroid gland and may originate from the mesenchymal cells of the capsule or stromal tissues of the thyroid gland.

Kikuchi et al. (7) previously reported a 60-yr-old male patient with primary synovial sarcoma of the thyroid gland. The patient had an ill-defined solid mass, which occupied almost the entire thyroid parenchyma and extended to the thyroid cartilage and surrounding muscles. The tumor revealed monophasic synovial sarcoma that was composed of spindle cells. In our case, a 15-yr-old boy with an encapsulated, biphasic synovial sarcoma without invasion into the adjacent structures underwent a complete resection. Kikuchi et al. (7) emphasized the cytologic findings of this tumor. The fine needle aspiration cytology showed a large quantity of spindle cells, either isolated cells or dense clusters around blood vessels in a radial fashion. In our case, the cytologic smear showed moderate cellularity with scattered benign-appearing follicular epithelial cells and several clusters of spindle-shaped cells or epithelioid cells with mild nuclear pleomorphism.

The main histologic differential diagnosis includes a spindle cell variant of medullary carcinoma, undifferentiated (anaplastic) carcinoma, and spindle epithelial tumor with thymus-like differentiation (SETTLE). The spindle cell variant of medullary carcinoma affects an older age group and is positive for synaptophysin, chromogranin, and calcitonin. The presence of amyloid deposits and neuroendocrine nuclear features favor medullary carcinoma. The undifferentiated carcinoma is uniformly positive for cytokeratin and shows an admixture of spindle cells, pleomorphic giant cells, and epithelioid cells. The poorly differentiated carcinoma shows solid cellular nests with a trabecular arrangement and is thyroglobulin and TTF-1 positive. Undifferentiated carcinomas affect an older age group than synovial sarcomas (10). SETTLE shows very similar clinical, histologic, and immunohistochemical features to synovial sarcomas, especially in the case of a monophasic pattern. SETTLE consists of bland, uniform-appearing spindle cells that merge with more epithelial-appearing structures, whereas a synovial sarcoma consists of more atypical-appearing and mitotically active tumor cells. The immunohistochemical profile of synovial sarcoma and SETTLE is very similar, but over 80% of synovial sarcomas are positive for CD99. Ultrastructural examination shows that spindle cells have a cell junction without basal lamina in SETTLE, but spindle cells of synovial sarcoma have no cell junction. Also, nests of epithelial cells in synovial sarcoma have basal lamina (11). A cytogenetic study may provide conclusive evidence to confirm the diagnosis of synovial sarcoma by detecting the SYT-SSX fusion gene transcripts using the reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction method (12).

Unusual locations make the diagnosis of synovial sarcoma difficult, especially when the synovial sarcoma occurs in the thyroid. Differential diagnosis from SETTLE is very difficult due to their similar clinical, histological, and immunohistochemical features. Ultrastructural and cytogenetic studies with recognition of synovial sarcoma are necessary to make a definitive diagnosis.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

The neck computed tomography reveals a well-demarcated solid mass at the superior and lateral aspect of the left thyroid gland, suggesting either a primary thyroid mass or soft tissue tumor.

Fig. 2

The fine needle aspiration cytology shows several cell clusters, which are composed of spindle-shaped (A) or epithelioid cells (B). The nuclei are round to oval and spindle-shaped and show finely granular chromatin with a moderate amount of pale eosinophilic cytoplasm.

Fig. 3

A capsule covers the mass and the thyroid gland, and the cut surface of the mass shows a well-demarcated, lobulated and tan-colored solid mass with rubbery consistency.

Fig. 4

Microscopically, the tumor shows a biphasic growth pattern (A). The spindle cell component consists of fascicles of atypical fibroblast-like cells, and the epithelial component is composed of solid nests of epithelioid cells with well-formed glandular structures (B). The periphery of the tumor shows more densely packed spindle cells with calcification (C). A focal hemangiopericytic growth pattern is present (D).

Fig. 5

On immunohistochemistry, the epithelial cells are diffusely and strongly stained with cytokeratin (A), whereas the spindle cells are diffusely stained with vimentin (B).

References

1. Weiss SW, Goldblum JR, Enzinger FM. Enzinger and Weiss's Soft Tissue Tumors. 2001. St. Louis, USA: Mosby;1483–1509.

2. Raney RB. Synovial sarcoma in young people: background, prognostic factors, and therapeutic questions. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2005. 27:207–211.

3. Nielsen GP, Shaw PA, Rosenberg AE, Dickersin GR, Young RH, Scully RE. Synovial sarcoma of the vulva: a report of two cases. Mod Pathol. 1996. 9:970–974.

4. Smith CJ, Ferrier AJ, Russell P, Danieletto S. Primary synovial sarcoma of the ovary: first reported case. Pathology. 2005. 37:385–387.

5. Holla P, Hafez GR, Slukvin I, Kalayoglu M. Synovial sarcoma, a primary liver tumor--a case report. Pathol Res Pract. 2006. 202:385–387.

6. Suster S, Moran CA. Primary synovial sarcomas of the mediastinum: a clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and ultrastructural study of 15 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005. 29:569–578.

7. Kikuchi I, Anbo J, Nakamura S, Sugai T, Sasou S, Yamamoto M, Oda Y, Shiratsuchi H, Tsuneyoshi M. Synovial sarcoma of the thyroid. Report of a case with aspiration cytology findings and gene analysis. Acta Cytol. 2003. 47:495–500.

8. Miettinen M, Virtanen I. Synovial sarcoma--a misnomer. Am J Pathol. 1984. 117:18–25.

9. Dickersin GR. Synovial sarcoma: a review and update, with emphasis on the ultrastructural characterization of the nonglandular component. Ultrastruct Pathol. 1991. 15:379–402.

10. Pilch BZ. Head and Neck Surgical Pathology. 2001. Philadelphia, USA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins;365–371.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download