Abstract

We report a case of anaplastic ganglioglioma. A 45-yr-old woman was admitted with a 5-month history of headache and dizziness, both of which progressed slowly. Preoperative magnetic resonance imaging revealed a strong enhancing mass in the left frontal lobe extending to the cingulate gyrus. Adjuvant radiation therapy and chemotherapy were given after gross total resection of the tumor. Histological and immunohistochemical studies showed an anaplastic ganglioglioma. Gangliogliomas of the central nervous system are rather uncommon tumors, and anaplastic ones are extremely rare. The pertinent literature regarding gangliogliomas is reviewed.

Although gangliogliomas of the central nervous system are rather uncommon tumors that consist of a mixture of neoplastic glial cells and differentiated ganglion cells, the disease entity is well recognized. They occur most frequently in children and in adults younger than 30 yr old (1). Gangliogliomas are typically associated with a long history of intractable seizures because they most often arise in the temporal lobe; the prognosis is usually favorable (1). In contrast, anaplastic gangliogliomas are very rare and their clinical course is poorly understood (2-6). The anaplastic change in gangliogliomas is more frequent in the pediatric population (3, 6). Here, we report a case of anaplastic ganglioglioma identified histologically at initial resection in a middle-aged woman.

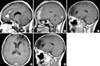

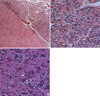

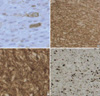

A 45-yr-old female patient presented with a history of headache and dizziness, both of which progressed slowly. A neurological examination showed nothing remarkable. Preoperative magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a left frontal lesion that was slightly hypointense on T1-weighted images and hyperintense on T2-weighted images. The lesion extended to the cingulate gyrus with peritumoral edema and strong contrast enhancement (Fig. 1A). Gross total resection of the tumor revealed a dark-brown, friable mass, consisting of a soft, aspiratable portion and a fibrous hypervascular nonaspiratable portion. Microscopically, the ganglioglioma contained atypical glial cells and scattered ganglion cells. The tumor cells infiltrated the gray matter and subarachnoid space (Fig. 2A). The tumor cells in the gray matter consisted of neoplastic ganglion cells and glial cells. Those in the subarachnoid space were mainly glial cells and showed increased cellularity, nuclear atypism, and occasional mitosis (Fig. 2B). The abnormally clustered ganglion cells lacked orderly distribution and polarity, and most had large nuclei with prominent nucleoli (Fig. 2C). The neoplastic ganglion cells were immunoreactive to synaptophysin and neuron specific enolase (NSE) (Fig. 3A, B). The atypical glial components were positive for glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) (Fig. 3C). A diagnosis of anaplastic ganglioglioma was made. The patient recovered postoperatively without any neurologic deficits. MRI taken 12 days postoperatively showed multiple irregularly shaped enhancing lesions along the resection margin of the left frontal lobe and cingulate gyrus (Fig. 1B). Two weeks after surgery, she received one cycle of intravenous nimustine HCl (ACNU, 60 mg) and cisplatin (CDDP, 60 mg). Subsequently, radiation therapy was administered in 30 doses for a total dose of 6,000 cGy over five weeks, and additional three cycles of chemotherapy with the same regimen were given. During chemotherapy, she was managed for pancytopenia. Five months later, follow-up MRI revealed that the remaining mass in the cingulate gyrus and resection margin had disappeared (Fig. 1C). She has shown intact neurological status and no other complications until now, and the last follow-up MRI at 35 months postoperatively demonstrated no evidence of recurrence (Fig. 1D, E).

The incidence of gangliogliomas has been reported to range from 0.4% to 7.6% in a series of brain tumors in a pediatric population (7). Central nervous system gangliogliomas are usually benign. Although malignant variants of ganglioglioma are said to be rare, Russell and Rubinstein estimated the rate of malignant change to be approximately 10% (1). Considering other reports, anaplastic gangliogliomas seem to account for 3-5% of gangliogliomas (6). However, the incidence remains unknown. Although malignant variants commonly occur in the supratentorial regions, some occur in other regions (8-12). Recently, Blumcke and Wiestler (13) reported that these tumors tend to occur in older patients with a mean age of 35±14.5 yr (range 10-88 yr). Macroscopically, gangliogliomas are usually firm well-circumscribed masses with a granular appearance on cut sections (1). According to Russell and Rubinstein (1), the microscopic criteria for the diagnosis of ganglioglioma are as follows: the tumor consists of a mixture of glial cells and neurons; the glial cells consist mostly of astrocytes; and the cells are identified as neurons only if Nissl substance can be demonstrated by cresyl violet staining or if they give rise to neuronal processes, as demonstrated using modified Bielschowski or Bodian stains. For neurons to be considered neoplastic, they must be either clearly heterotopic (located away from the gray matter), or atypical (showing disorientation, bizarre shapes or sizes, and nuclei with hyperchromatism and frequent binucleation) (7). Confirmation of the neuronal component may require the use of immunohistochemical markers, including synaptophysin, neurofilament protein, NSE (1, 7), and NeuN. The astroglial components are positive for GFAP and S-100 proteins. In our case, we found neoplastic glial cells and neuronal cells that were clustered and lacked orderly distribution and polarity; most had large nuclei with prominent nucleoli. The tumor cells revealed definite immunoreactivity for synaptophysin, NSE, and GFAP. The Ki-67 labeling index (LI) in our case was 20%, while the reported Ki-67 LI in ganglioglioma is generally less than 10% (Fig. 3D) (6). Therefore, we made a diagnosis of diagnosed anaplastic ganglioglioma in our case.

The manifestation of malignant biological features in some gangliogliomas, as with other glial tumors, results from anaplastic histological features at initial resection (3, 9, 12, 14-19) (Table 1) or anaplastic transformation of a previously benign ganglioglioma (4, 8, 10, 11, 20-22) (Table 2). These tumors tend to occur in older patients compared with the usual onset age of ganglioglioma, especially anaplastic gangliogliomas found at initial resection.

Total removal is recommended and regarded as a good prognostic factor for the treatment of ganglioglioma without anaplastic features (2, 5, 7). The benefits of radiation therapy or chemotherapy for the treatment of ganglioglioma have not been clearly defined (4, 7). Although radiation therapy has uncertain benefits, it is generally given to patients with incomplete resection of the tumor or recurrent tumor, and to those with a tumor histology showing anaplastic features or oligodendroglial-like cells (7). Although the optimum treatment for anaplastic ganglioglioma has not been established, our patient, who was treated surgically with adjuvant therapy, is still alive without tumor progression or recurrence. This suggests that adjuvant radiation and chemotherapy is of some value.

The biological nature of these anaplastic variants is poorly understood because there are few documented cases. The survival rate is lower when the tumor is localized in the midline structures or when there are anaplastic features (2, 7, 23). Based on their multivariate analysis, Park et al. (24) reported that the two most important favorable prognostic factors affecting the overall survival were low tumor grade and gross total resection. However, other authors reported that the histological grade of the ganglioglioma is not a predictor of poor outcome (5, 7). Therefore, the prognosis of gangliogliomas with malignant histological features remains uncertain. Although predicting the prognosis of anaplastic gangliogliomas is difficult, some authors stated that cell kinetic studies, such as MIB-1 staining, may be useful for predicting the prognosis (6, 8).

Here, we report on a very rare case of anaplastic ganglioglioma that occurred in a middle-aged woman. Although the relationship between the clinical outcome and histological grade remains unclear and the effects of radiation therapy and chemotherapy on gangliogliomas are uncertain, adjuvant radiation therapy and chemotherapy appear to have been effective, at least so far. Further long-term studies on a larger number of ganglioglioma patients are necessary to better understand the clinical outcome and appropriate treatment strategies.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Preoperative MRI showing an irregular strong enhancing mass in the left frontal lobe extending to the cingulate gyrus (A). MRI on the 12th postoperative day showing multiple irregularly shaped enhancing lesions along the resection margin of the left frontal lobe and cingulate gyrus (B). After chemotherapy and radiation therapy, MRI 5 months postoperatively revealed that the irregular enhancing lesions in the resected margin of the left frontal lobe and cingulate gyrus had disappeared (C). And, the last follow-up MRI at 35 months postoperatively shows no evidence of recurrence (D, E).

Fig. 2

Photomicrographs showing the histopathology of the ganglioglioma in our case. (A) The tumor cells infiltrated the gray matter and subarachnoid space. The tumor cells in the gray matter consisted of neoplastic ganglion cells and glial cells. Those in the subarachnoid space (asterisk) are mainly glial cells and show increased cellularity, nuclear atypism, and occasional mitosis (hematoxylin and eosin, original magnification, ×40). (B) Atypical glial cells (arrow) and scattered ganglion cells (white arrow) constitute the ganglioglioma. Note the increased cellularity and nuclear atypism of the glial cells (hematoxylin and eosin, original magnification, ×400). (C) Neoplastic ganglion cells (arrow) are clustered abnormally and lack orientation and polarity. Most have large nuclei with prominent nucleoli (hematoxylin and eosin, original magnification, ×400).

Fig. 3

Immunostaining features suggestive of anaplastic gangliogliomas. Neoplastic ganglion cells are positive for NSE (A) and synaptophysin (B). (C) Glial components are positive for GFAP, and scattered ganglion cells are negative. (D) The Ki-67 LI is high (20%) in the region of anaplastic transformation.

References

1. Russell DS, Rubinstein LJ. Pathology of tumors of the nervous system. 1989. 5th Ed. Baltimore, USA: Williams & Wilkins;289–307.

2. Haddad SF, Moore SA, Menezes AH, VanGilder JC. Ganglioglioma: 13 years of experience. Neurosurgery. 1992. 31:171–178.

3. Hall WA, Yunis EJ, Albright AL. Anaplastic ganglioglioma in an infant: case report and review of the literature. Neurosurgery. 1986. 19:1016–1020.

4. Kitano M, Takayama S, Nagao T, Yoshimura O. Malignant ganglioglioma of the spinal cord. Acta Pathol Jpn. 1987. 37:1009–1018.

5. Lang FF, Epstein FJ, Ransohoff J, Allen JC, Wisoff J, Abbott IR, Miller DC. Central nervous system gangliogliomas. Part 2: clinical outcome. J Neurosurg. 1993. 79:867–873.

6. Wolf HK, Muller MB, Spanle M, Zentner J, Schramm J, Wiestler OD. Ganglioglioma: a detailed histopathological and immunohistochemical analysis of 61 cases. Acta Neuropathol (Berl). 1994. 88:166–173.

7. Johannsson JH, Rekate HL, Roessmann U. Gangliogliomas: pathological and clinical correlation. J Neurosurg. 1981. 54:58–63.

8. Jay V, Squire J, Becker LE, Humphreys R. Malignant transformation in a ganglioglioma with anaplastic neuronal and astrocytic components: report of a case with flow cytometric and cytogenetic analysis. Cancer. 1994. 73:2862–2868.

9. Matsuzaki K, Uno M, Kageji T, Hirose T, Nagahiro S. Anaplastic ganglioglioma of the cerebellopontine angle. Case report. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 2005. 45:591–595.

10. Di Patre PL, Payer M, Brunea M, Delavelle J, De Tribolet N, Pizzolato G. Malignant transformation of a spinal cord ganglioglioma--case report and review of the literature. Clin Neuropathol. 2004. 23:298–303.

11. Mittler MA, Walters BC, Fried AH, Sotomayor EA, Stopa EG. Malignant glial tumor arising from the site of a previous hamartoma/ganglioglioma: coincidence or malignant transformation? Pediatr Neurosurg. 1999. 30:132–134.

12. Hirose T, Kannuki S, Nishida K, Matsumoto K, Sano T, Hizawa K. Anaplastic ganglioglioma of the brain stem demonstrating active neurosecretory features of neoplastic neuronal cells. Acta Neuropathol (Berl). 1992. 83:365–370.

13. Blümcke I, Wiestler OD. Gangliogliomas: an intriguing tumor entity associated with focal epilepsies. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2002. 61:575–584.

14. Allegranza A, Pileri S, Frank G, Ferracini R. Cerebral ganglioglioma with anaplastic oligodendroglial component. Histopathology. 1990. 17:439–441.

15. Araki M, Fan J, Haraoka S, Moritake T, Yoshii Y, Watanabe T. Extracranial metastasis of anaplastic ganglioglioma through a ventriculoperitoneal shunt: a case report. Pathol Int. 1999. 49:258–263.

16. Campos MG, Zentner J, Ostertun B, Wolf HK, Schramm J. Anaplastic ganglioglioma: case report and review of the literature. Neurol Res. 1994. 16:317–320.

17. Danjoux M, Sabatier J, Uro-Coste E, Roche H, Delisle MB. Anaplastic temporal ganglioglioma with spinal metastasis. Ann Pathol. 2001. 21:55–58.

18. Nair V, Suri VS, Tatke M, Saran RK, Malhotra V, Singh D. Gangliogliomas: a report of five cases. Indian J Cancer. 2004. 41:41–46.

19. Suzuki H, Otsuki T, Iwasaki Y, Katakura R, Asano H, Tadokoro M, Suzuki Y, Tezuka F, Takei H. Anaplastic ganglioglioma with sarcomatous component: an immunohistochemical study and molecular analysis of p53 tumor suppressor gene. Neuropathology. 2002. 22:40–47.

20. Kurian NI, Nair S, Radhakrishnan VV. Anaplastic ganglioglioma: case report and review of literature. Br J Neurosurg. 1998. 12:277–280.

21. Sasaki A, Hirato J, Nakazato Y, Tamura M, Kadowaki H. Recurrent anaplastic ganglioglioma: pathological characterization of tumor cells. Case report. J Neurosurg. 1996. 84:1055–1059.

22. Whittle IR, Mitchener A, Atkinson HD, Wharton SB. Anaplastic progression in low grade glioneural neoplasms. Acta Neuropathol (Berl). 2002. 104:215.

23. Demierre B, Stichnoth FA, Hori A, Spoerri O. Intracerebral ganglioglioma. J Neurosurg. 1986. 65:177–182.

24. Park SH, Vinters HV. Ganglion cell tumors. Korean J Pathol. 2002. 36:167–174.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download