Abstract

Placenta increta is an uncommon and life-threatening complication of pregnancy characterized by complete or partial absence of the decidua basalis. Placenta increta usually presents with vaginal bleeding during difficult placental removal in the third-trimester. Although placenta increta may complicate first and early second-trimester pregnancy loss, the diagnosis can be very difficult during early pregnancy and thus the lesion is difficult to identify. We encountered with a woman who was diagnosed with placenta increta after receiving emergency hysterectomy due to intraperitoneal bleeding 2 months after an uncomplicated dilatation and curettage in the first trimester. Therefore, we report this case with a brief review of the literature.

Placenta increta is a life-threatening complication of pregnancy characterized by complete or partial absence of the decidua basalis and imperfect development of the fibrinoid layer (Nitabuch layer). Although the incidence of placenta accreta/increta/percreta is reported 1:2500-7000, this abnormally adherent placental condition assumes considerable significance clinically because of morbidity and, at times, mortality from severe hemorrhage, uterine perforation, and infection (1-3).

Placenta increta usually presents with vaginal bleeding during difficult placental removal in the third trimester. Placenta increta may also complicate first and early second-trimester pregnancy loss, causing profuse post-curettage hemorrhage (4-6). Although an association has been noted with placenta previa, previous uterine curettage, previous cesarean section, multiparity (6 or more), and advanced maternal age (7-9), the definite etiology of placenta increta remains unknown.

We encountered with a woman who was diagnosed with placenta increta after receiving emergency hysterectomy due to intraperitoneal bleeding 2 months after an uncomplicated dilatation and curettage in the first trimester. Therefore, we report this case with a brief review of the literature.

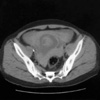

A 35-yr-old woman, gravida 5, para 2, was admitted because of acute abdominal pain and syncope 8 weeks after an uncomplicated dilatation and curettage. Her obstetric history included two times of vaginal delivery and three times of dilatation and curettage. She underwent dilatation and curettage 10 months prior to admission for a missed abortion, 2 and 4 months prior to admission for elective abortion. She stated that she experienced a small amount of vaginal spotting three days before admission. When she came to the hospital, her body temperature was 36℃, blood pressure 90/60 mmHg, and pulse rate 84 beats/min. Physical examination showed diffuse tenderness on entire abdomen with significant rebounding pain and muscle guarding. The complete blood count showed hemoglobin of 7.6 g/dL and hematocrit of 21.1%. Urine pregnancy test was negative. The diagnosis of internal bleeding associated with hypovolemic shock was strongly suspected clinically. She received 3,000 mL of fluid infusion including colloid and crystalloid and 2 units of packed red blood cells (RBC) at the emergency room. Abdomen-pelvic computed tomography (CT) showed a 6×5 cm-sized exophytically bulging vascular mass on the left uterine cornual portion (Fig. 1). Based on imaging findings, acquired arterio-venous malformation rupture was suspected. Even after vigorous fluid and blood resuscitation, her hemoglobin further decreased to 4.4 g/dL and blood pressure remained unstable. She was taken immediately into the operation room. Operative findings revealed extensive hemoperitoneum (about 5,000 mL including old clot and fresh blood) and a 4×3 cm-sized cystic lesion on the left fundal area of the myometrium suspicious of vascular malformation. The uterus was slightly enlarged. Bilateral ovaries and tubes appeared edematous and congested, and continuous oozing from both ovaries and retroperitoneal space was noted. Total abdominal hysterectomy with bilateral salpingooophorectomy was performed. In total, 13 units of packed RBC and 5 units of fresh frozen plasma were transfused perioperatively. Her serum β-human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) level was less than 2 mIU/mL. Histological examination revealed that in the superficial and deep myometrium extending close to the serosal surface, there were multifocal aggregates of intermediate trophoblasts and chorionic villi, which showed degenerative features and were surrounded by a large amount of fibrin (Fig. 2). There was no definite evidence of decidua basalis in the junction of placenta and myometrium. The appearance was that of a placenta increta. It was presumed that the involvement of a deep myometrial vessel was responsible for the torrential hemorrhage.

She was transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU) post-operatively and received 5 more units of packed RBC and 8 units of platelet concentrates. She was extubated on post-operative day 1 and transferred to the general ward. Her condition remained stable, and she made a favorable progress. She was discharged one week later.

Placenta increta usually presents with vaginal bleeding during difficult placental removal in the third trimester. Placenta increta may also complicate first and early second-trimester pregnancy loss, causing profuse post-curettage hemorrhage. Early recognition of the condition may improve the outcome, since it provides the obstetrician the opportunity to deal promptly with such obstetrical emergency. However, most cases of placenta increta have no preceding symptoms, thus a higher degree of suspicion for early diagnosis should rely on known risk factors mentioned above.

The antenatal diagnosis of placenta increta may be based on real-time ultrasound, power Doppler, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (10, 11). The diagnostic value of ultrasonographic examination in the antenatal diagnosis of asymptomatic placenta accreta is not clear. Finberg et al. (12) reported a positive predictive value of 78% and negative predictive value of 94%. However, Lam et al. (13) found that ultrasound was only 33-percent sensitive for detecting placenta accreta. Chou et al. (14) described successful use of three-dimensional color power Doppler imaging for diagnosis of placenta percreta. MRI has also been proposed as a diagnostic tool in detecting placenta accreta, but no additive advantage was found over ultrasonography (13).

The clinical manifestations of placenta accreta such as bleeding, uterine rupture, invasion of the bladder, and uterine inversion depend on the site of implantation, depth of myometrial penetration, and the extent of abnormally adherent placenta (15). In the majority of women with antepartum hemorrhage, coexisting placenta previa may be the cause. Myometrial invasion by placental villi at the site of a previous cesarean scar may lead to uterine rupture before the onset of labor (2). With extensive involvement of placenta increta, hemorrhage becomes profuse as delivery of the placenta is attempted. Successful treatment depends on immediate blood replacement therapy and prompt hysterectomy. In the past, the most common form of conservative management was manual removal of the placenta as much as possible and then packing of the uterus. According to the study done by Fox, 25 percent of women died after receiving conservative management (9). Therefore conservative management is probably appropriate only for partial placenta accreta where bleeding is minimal. Alternative measures include uterine or internal iliac artery ligation or angiographic embolization. Liu et al. (4) reported four cases in uterine artery embolization was done to control bleeding. The uterus was preserved and heavy uterine bleeding was controlled satisfactorily.

There could be a few other reasons for hemoperitoneum, including the rupture of acquired uterine arteriovenous malformation, which was found on CT as in this case. Previous uterine surgeries, such as curettage and cesarean section are important factors that cause acquired uterine arteriovenous malformation. Previous pregnancy, infection, gestational trophoblastic disease, endometrial or cervical cancers can be a factor as well (16). Arteriovenous malformation could be diagnosed by angiography, ultrasonography, or CT. The existence of arteriovenous fistula could not be assured in this case, because additional examination was not taken. However, the possibility of coexistent arteriovenous malformation was considerably low according to pathologic findings. Also, ectopic pregnancy, which is a common cause of large hemoperitoneum, was not taken into account due to the negative pregnancy test result. Placental site trophoblastic tumor characterized by the presence of proliferating trophoblastic tissue deeply invading the myometrium could be another cause. However, her serum β-hCG level was less than 2 mIU/mL and the pathologic findings were not suitable for placental site trophoblastic tumor.

Four cases of placenta increta at first trimester similar to this case have been reported in Korea. However, Choi et al. (17) reported uterine rupture in normal intrauterine pregnancy at 13 gestational weeks due to placenta increta. The Lee et al. (18) study was different from the current study in that missed abortion and H-mole were suspected 50 days after dilatation and curettage due to persistent vaginal bleeding with an elevated β-hCG level of 161 mIU/mL. Kim et al. (19) reported an elevated β-hCG level of 2,470 mIU/mL in a case with suspected gestational trophoblastic disease associated with arteriovenous malformation, which was detected from imaging studies that were carried out due to 2 weeks of vaginal bleeding. Also, the case reported by Roh et al. (20) was different in that there was massive acute bleeding immediately after dilatation and curettage. This is the first case report of placenta increta found in a woman with a normal β-hCG level who developed hemoperitoneum 60 days after dilatation and curettage.

Our case suggests that in women at risk for invasive placentation who have had recent spontaneous or therapeutic abortion and present with abnormal uterine bleeding or intraperitoneal bleeding, placenta increta should be considered.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis. The CT demonstrates a vascular mass on the left uterine cornual portion.

Fig. 2

Histologic section of the uterine mass (A). In the superficial and deep myometrium, there were multifocal aggregates of intermediate trophoblasts and chorionic villi surrounded by a large amount of fibrin (H&E, ×40). (B) There was no definite evidence of decidua basalis in the junction of placenta and myometrium (H&E, ×200).

References

1. Breen JL, Neubecker R, Gregori CA, Franklin JE. Placenta accreta, increta, and percreta. A survey of 40 cases. Obstet Gynecol. 1977. 49:43–47.

2. Berchuck A, Sokol RJ. Previous cesarean section, placenta increta, and uterine rupture in second-trimester abortion. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1983. 145:766–767.

3. Clark SL, Koonings PP, Phelan JP. Placenta previa/accreta and prior cesarean section. Obstet Gynecol. 1985. 66:89–92.

4. Liu X, Fan G, Jin Z, Yang N, Jiang Y, Gai M, Guo L, Wang Y, Lang J. Lower uterine segment pregnancy with placenta increta complicating first trimester induced abortion: diagnosis and conservative management. Chin Med J. 2003. 116:695–698.

5. Ecker JL, Sorem KA, Soodak L, Roberts DJ, Safon LE, Osathanondh R. Placenta increta complicating a first-trimester abortion. A case report. J Reprod Med. 1992. 37:893–895.

6. Harden MA, Walters MD, Valente PT. Postabortal hemorrhage due to placenta increta: a case report. Obstet Gynecol. 1990. 75:523–526.

7. Jacques SM, Qureshi F, Trent VS, Ramirez NC. Placenta accreta: mild cases diagnosed by placental examination. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 1996. 15:28–33.

8. Miller DA, Chollet JA, Goodwin TM. Clinical risk factors for placenta previa-placenta accreta. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997. 177:210–214.

10. Gielchinsky Y, Rojansky N, Fasouliotis SJ, Ezra Y. Placenta accreta-summary of 10 years: a survey of 310 cases. Placenta. 2002. 23:210–214.

11. Suh YH, Song EH, Kim DH, Lee YH, Park HY, Koh KS, Park CH. A clinical study of placental adhesions: placenta accreta, placenta increta, and placenta percreta. Korean J Obstet Gynecol. 2003. 46:81–88.

12. Finberg HJ, Williams JW. Placenta accreta: prospective sonographic diagnosis in patients with placenta previa and prior cesarean section. J Ultrasound Med. 1992. 11:333–343.

13. Lam G, Kuller J, McMahon M. Use of magnetic resonance imaging and ultrasound in the antenatal diagnosis of placenta accreta. J Soc Gynecol Investig. 2002. 9:37–40.

14. Chou MM, Ho ES, Lee YH. Prenatal diagnosis of placenta previa accreta by transabdominal color Doppler ultrasound. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2000. 15:28–35.

15. Haynes DI, Smith JH, Fothergill DJ. A case of placenta increta presenting in the first trimester. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2000. 20:434–435.

16. Yang JJ, Xiang Y, Wan XR, Yang XY. Diagnosis and management of uterine arteriovenous fistulas with massive vaginal bleeding. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2005. 89:114–119.

17. Choi GD, Choi WK, Lee HS, Kim CB, Lee GN. A case of spontaneous rupture of the uterus with placenta increta in early pregnancy. Korean J Obstet Gynecol. 1996. 39:1359–1364.

18. Lee YT, Lee MH, Moon H, Hwang YY. A case of placenta increta which was found about 50 days after induced abortion at 1st trimester. Korean J Obstet Gynecol. 2000. 43:1298–1301.

19. Kim MJ, Kwen I, Kim JA, Hur SY, Kim SJ, Kim EJ. A case of placenta increta presenting as delayed postabortal hemorrhage. Korean J Obstet Gynecol. 2005. 48:755–759.

20. Roh HJ, Park SK, Hwang JY, Cho HJ, Lee SH, Lee HA, Choi JW, Kim SH, Chae HD, Kim CH, Kim GR, Kang BM. Placenta increta complicating a first trimester abortion: a case report. Korean J Obstet Gynecol. 2004. 47:1828–1832.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download