Abstract

In order to establish optimal management for aortoenteric fistula (AEF) the records of five patients treated for AEF (four aortoduodenal and one aortogastric fistula) were retrospectively reviewed. The arterial reconstruction procedures were selected according to the surgical findings, underlying cause, and patient status. In situ aortic reconstructions with prosthetic grafts were performed on three patients who had no gross findings of periaortic infection, whereas axillo-bifemoral bypass was carried out in the other two patients with periaortic purulence. In all patients, after retroperitoneal irrigation a pedicled omentum was used to cover the aortic graft or aortic stump. In the preoperative abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan there was a periaortic air shadow in four out of five patients. There was no surgical mortality or graft infection observed during a mean follow-up period of 40 months (range, 24-68 months). Therefore, the treatment results of an AEF can be improved using intravenous contrast-enhanced abdominal CT for rapid diagnosis and selection of an appropriate surgical procedure based on the surgical findings and underlying cause.

An aortoenteric fistula (AEF) is a rare but life-threatening cause of gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding. Patients with an AEF are commonly encountered as a medical emergency associated with acute GI bleeding. Although the reported incidence of AEF is low, immediate recognition and management is essential for the patient's survival.

AEF can be classified into primary and secondary types according to the presence or absence of a prior history of aortic surgery (1). Two major concerns for the treatment of AEF are bleeding control at the time of the initial presentation and the prevention of late complications associated with bleeding or infection. Early diagnosis and prompt surgical treatment is essential for reducing the risk of a massive GI hemorrhage. A variety of surgical procedures have been performed to reduce the incidence of postoperative infectious complications. These include an aortic resection followed by an axillo-bifemoral bypass (AxBFB) (2), in situ aortic reconstruction using a prosthetic graft, antibiotic-impregnated prosthetic graft (3), autogenous femoral vein graft (4), or cryopreserved aortic allograft (5, 6).

We successfully treated five patients with an AEF and report their management.

The medical records of five consecutive patients (all male, mean age 65±9.2 yr, range 55-76 yr), who were treated for an AEF (four primary and one secondary AEF; four aortoduodenal and one aortogastric fistula) between March 1999 and February 2003 were retrospectively reviewed.

Preoperatively, intravenous contrast-enhanced abdominal computed tomography (CT) scans were performed in all patients. Gastroduodenal fiberscopic examination was performed in one patient, but the bleeding focus could not be located due to a large hematoma in the stomach.

For bacterial culture, a preoperative blood culture was obtained in two patients. Intraoperative tissue culture with periaortic tissue around the AEF, and postoperative drain fluid culture were obtained in all patients.

For the arterial blood flow reconstruction, AxBFB after the aortic aneurysmectomy was done in two patients and an in situ aortic reconstruction was performed in three patients. The procedures were selected according to the surgical findings; AxBFB for patients with periaortic purulence and an in situ aortic reconstruction for those with no evidence of gross purulence.

After periaortic debridement and irrigation with 1% povidone iodine solution, the aortic stump or aortic prosthetic graft was covered with the greater omentum. The greater omentum was dissected from its attachment to the transverse colon and mobilized to the infrarenal aorta through an opening at the transverse mesocolon. Before closing the abdominal wall, closed suction drains were placed around the site of the infrarenal abdominal aorta.

Postoperatively, intravenous antibiotics were given for four weeks followed by oral antibiotics for two months or longer. The selection of antibiotics depended on the results of the bacterial cultures from the blood, retroperitoneal tissue, and peritoneal drainage fluid. Parenteral nutrition was provided if enteric feeding was delayed.

All patients were male with a mean age of 66 yr and presented with acute GI bleeding to the Emergency Department. Table 1 shows the clinical features of the patients at the initial presentation. The time interval between the herald bleeding and the episode of large GI hemorrhage was 2.5 hr (median, range 1-48 hr).

The underlying causes of the AEF were an aortic aneurysm (three patients with infrarenal abdominal aortic aneurysm [AAA] and one patient with Type IV thoracoabdominal aneurysm) and one para-anastomotic pseudoaneurysm in a patient who underwent an aortobifemoral bypass graft eight years earlier due to chronic aortoiliac occlusive disease. Table 2 summarizes the surgical findings and procedures.

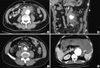

In a patient with an aortogastric fistula, gastric fistula opening was located at the posterior wall of the gastric cardia close to the esophagocardial junction. A retrospective review of the preoperative abdominal CT scans revealed periaortic air shadows in four (80%) patients (Fig. 1).

After aneurysmectomy, sigmoid colon ischemia developed in one patient. This patient was treated with a sigmoid colectomy and Hartmann's colostomy before AxBFB grafting. Table 3 shows the bacteriologic examination results. A postoperative gastropleural fistula (GPF, Fig. 2) developed in a patient with TAA, and the aortogastric fistula required a second operation to close the gastric fistula and thoracotomy tube for drainage. No mortality or graft infection developed during the follow-up period (mean 40 months; range, 24 months to 68 months) (Table 4).

AEF can occur as a rare late complication of aortic reconstructive surgery, or even less frequently, as a complication of an untreated AAA (7). The optimal management for AEF consists of an early diagnosis before the occurrence of major bleeding, prompt bleeding control by expeditious control of the proximal aorta, closure of the enteric fistula without spilling of the bowel contents, a durable arterial reconstruction, and the prevention of postoperative complications, particularly graft infection.

The role of the primary physician in the Emergency Department is important for early detection of AEF. AEF should be on the list of differential diagnoses while evaluating GI bleeding. Although GI hemorrhage, abdominal pain, and a pulsatile abdominal mass are the diagnostic triad of AEF, the signs of a pulsatile abdominal mass can be masked by abdominal distension. Capaldo and Amin (8) reported abdominal pain and a pulsatile mass in 32% and a pulsating abdominal mass in 25% of their AEF patients.

Herald bleeding occurred in 60% of our patients, and the time interval between the initial bleeding and the massive GI hemorrhage ranged from one hour to two days, which is similar to other reports (1, 8, 9). Theoretically, this window period provides an opportunity to perform definitive surgical treatment for the AEF.

Currently, intravenous contrast-enhanced abdominal CT can be easily performed in an emergent situation. Spiral CT provides not only diagnostic clues for an AEF but also anatomical information for later aortic surgery. Intravenous contrast- enhanced abdominal CT has been recommended as an initial diagnostic test for AEF (1, 3, 6, 9). The CT findings suggestive of AEF are air bubbles around the aorta, bowel wall edema around the aorta, the loss of a fatty plane between the aorta and GI tract, and rarely, visualization of the fistula itself. Of these findings, a periaortic air shadow was reported to be a specific finding for the diagnosis of an aortic graft infection or AEF (10, 11). Periaortic air shadows were found in 80% of patients by a retrospective review of the preoperative abdominal CT scans.

In order to reduce the risk of infectious complications such as a graft infection, retroperitoneal debridement and irrigation with an antiseptic solution was performed and pedicled omentum was used to cover up the aortic stump or aortic graft.

There has been some debate regarding the optimal arterial reconstruction procedure after removing the infected aneurysm or aortic graft in patients with an aortic graft infection or infected aortic aneurysm, and either an in situ aortic reconstruction (1, 12) or axillobifemoral bypass grafting have been proposed (1, 7, 9). In previous reports, (3, 5, 9) the great omentum was used to wrap around the prosthetic graft or cover the infected surgical field for the purpose of preventing a graft infection. However, there have been no randomized clinical studies demonstrating the anti-bacterial effects of omental tissue to date. Regarding the duration of postoperative antibiotic therapy, Saers and Scheltinga (1) recommended at least 1 week of antibiotic therapy following negative blood culture and 4 to 6 weeks of systemic antibiotic therapy if blood cultures were positive. The duration of antibiotic therapy can be determined by the results of blood culture and clinical findings of the patients. In a primary AEF, chronic mechanical irritation between the bowel wall and aneurismal wall appears to provide watertight adhesion between the two tissue planes. To our knowledge, high-pressure aortic blood can create a one-way fistula into the bowel lumen and massive arterial bleeding can clean the bowel lumen. These properties of primary AEF might be associated with the lower rate of graft infection after an in situ aortic reconstruction.

In summary, early diagnosis and prompt surgical treatment are essential steps for an improved treatment outcome. For the early diagnosis of an AEF, intravenous contrast-enhanced abdominal CT imaging can provide a rapid and effective diagnosis even in an emergent situation. While there is no optimal surgical procedure for AEF to date, the most appropriate procedure can be selected based on the surgical findings, underlying cause of the AEF, and patient status. However, further studies will be needed to determine the efficacy of the omentum in preventing infections.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Preoperative contrast-enhanced abdominal CT scans in a patient with an aortoenteric fistula (AEF); four out of five patients showed periaortic air shadows (arrows).

Fig. 2

(A) Preoperative CT scan in a patient with an aortogastric fistula shows a type IV thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysm and a markedly distended stomach. (B) Postoperative upper GI series with gastrografin shows a gastropleural fistula (GPF, arrow) in the same patient.

References

2. Bacourt F, Koskas F. Axillobifemoral bypass and aortic exclusion for vascular septic lesions: a multicenter retrospective study of 98 cases. French University association for Research in Surgery. Ann Vasc Surg. 1992. 6:119–126.

3. Bandyk DF, Novotney ML, Johnson BL, Back MR, Roth SR. Use of rifampin-soaked gelatin-sealed polyester grafts for in situ treatment of primary aortic and vascular prosthetic infections. J Surg Res. 2001. 95:44–49.

4. Clagett GP, Valentine RJ, Hagino RT. Autogenous aortoiliac/femoral reconstruction from superficial femoral-popliteal veins: feasibility and durability. J Vasc Surg. 1997. 25:255–266.

5. Kieffer E, Gomes D, Chiche L, Fleron MH, Koskas F, Bahnini A. Allograft replacement for infrarenal aortic graft infection: early and late results in 179 patients. J Vasc Surg. 2004. 39:1009–1017.

6. Leseche G, Castier Y, Petit MD, Bertrand P, Kitzis M, Mussot S, Besnard M, Cerceau O. Long-term results of cryopreserved arterial allograft reconstruction in infected prosthetic grafts and mycotic aneurysms of the abdominal aorta. J Vasc Surg. 2001. 34:616–622.

7. Santilli SM, Goldstone J. Yao JST, Pearce WH, editors. Aortoenteric fistula. Arterial surgery. Management of Challenging Problems. 1996. Stanford, CO: Appleton & Lange;209–219.

8. Capaldo GR, Amin RM. Aortoduodenal fistula. Two case reports and a review of the literature. J Cardiovasc Surg Torino. 1996. 37:567–570.

9. Tareen AH, Schroeder TV. Primary aortoenteric fistula: two new case reports and a review of 44 previously reported cases. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 1996. 12:5–10.

10. Mark AS, Moss AA, McCarthy S, McCowin M. CT of aortoenteric fistulas. Invest Radiol. 1985. 20:272–275.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download