INTRODUCTION

Syringocystadenocarcinoma papilliferum (SCACP) is listed in the WHO classification of skin tumor as the malignant form of syringocystadenoma papilliferum (SCAP) (1). Most lesions seem to have arisen from long-standing SCAP (2). Histopathologically, SCACP has many structural similarities with SCAP, but it can be differentiated from SCAP in that it has an asymmetric and poorly circumscribed structure of tumor, often extending deep into the subcutaneous fat, and atypical cells, many of which are in mitosis (2).

To our knowledge, no case of SCACP have been reported in the Korean medical literature. Herein we report a case of SCACP occurring on the right supra-pubic area of a 65-yr-old Korean male patient.

CASE REPORT

A 65-yr-old Korean man presented with a single nodule on the right supra-pubic area. He had had the lesion for 2 yr. The patient stated that the lesion began as a bean-sized papule and had increased gradually in size with time. It also become painful and hemorrhagic. He had suffered from limitation of motion of both legs because of osteomyelitis. His personal medical history included hypertension with regular medication. Physical examination revealed a single, 3.4×3.5 cm, erythematous, dome-shaped, and firm tumor surrounded by bloody crust on the right supra-pubic area (Fig. 1). Regional lymph nodes were not palpable, and the physical examination did not reveal any remarkable findings except for the mass.

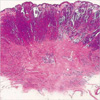

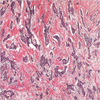

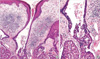

Histopathologic examination revealed a tumor with a solid and cystic pattern in the upper dermis (Fig. 2) and a tumor of numerous irregular shaped structures in the deep dermis (Fig. 3). Cystic invagination that connected to the skin surface through infundibular structures was extending to the dermis (Fig. 4A). The lower portion of cystic invagination was composed of multiple layered epithelium with decapitation on the luminal surface of the cells. There was a dense infiltration of numerous plasma cells and lymphocytes in the stroma of tumor (Fig. 4B). Variable degrees of nuclear atypia with large and hyperchromatic nuclei and mitotic figures were observed in these tumor cells (Fig. 5). Based on these histopathological findings, the diagnosis of SCACP was made. Immunohistochemically the tumor cells showed positive reaction to gross cystic disease fluid protein (GCDFP)-15, but negative reaction to carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) or human milk fat globules (HMFG)-1.

Laboratory tests including complete blood count and urinalysis were within normal limits or negative. Liver function tests and hepatitis B serologic tests revealed chronic hepatitis B. Tumor markers (CEA, α-fetoprotein, prostate specific antigen, and CA19-9), chest radiography, hepatobiliary sonography and gastrocolonoscopy did not show any internal malignancy or metastasis. A computed tomography (CT) of abdomen and pelvis could not be checked because of the patient's lower leg deformity.

Wide excisional surgery was performed to remove the tumor. There has not been any signs of recurrence or metastasis for 2 yr after the opertaion.

DISCUSSION

SCACP is one of the sweat gland carcinomas and is regarded as the malignant counterpart of SCAP (1). Although SCAP is frequently encountered clinically, SCACP is rarely observed and its clinical and histologic characteristics are not well known. Only eight cases of SCACP have been reported in the literature (3-8) (Table 1). The male (n=4)-to-female (n=4) ratio was 1:1. The patients' age ranged from 47 to 74 yr, having SCACP in their scalp. Clinically, the lesion shows skin-colored or yellowish papules or nodules that remain unchanged for many years but then begin to enlarge suddenly with bleeding or ulceration (2). Usually the lesion is covered with crusts as a consequence of secretion of apocrine epithelial cells (2). Its size varies from 2.5 to 13 cm. The duration of disease progression from the lesion to SCACP has been more than scores of years, but in cases of Arai et al. (7) and our case rapid development for two years was observed. Only surgical excision was performed in all reported cases.

Histopathologically, as in SCAP, tumor shows deep epidermal cystic invaginations containing numerous papillae. Neoplastic cells lining the cystic cavities are connected to the skin surface through funnel-shaped structures lined by infundibular epithelium. The upper part of invaginations is made up of keratinizing squamous epithelium, whereas the lower part and papillae are composed of two- or multi-layered epithelium. Cells of the inner layer have columnar with oval nuclei and abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and decapitation on the luminal surface, while the cells of the outer layer are small, cuboidal of flattened and have scanty cytoplasm and oval nuclei. Stroma of the tumor contains a dense inflammatory infiltrate, composed of numerous plasma cells and lymphoid cells (8). Occasionally, numerous normal apocrine glands can be found. However, SCACP can be different from SCAP in that it has an asymmetric structure of tumor and the boundary is not clear; often tumor cells infiltrate the deep dermis or subcutaneous fat in tubular, cystic or solid types; neoplastic cells exhibit crowed nuclei, variable degrees of nuclear atypia, and numerous mitotic figures (2, 8). From the above figdings, SCACP can be considered malignant. Our case could be diagnosed as SCACP since it was shown that tumor cells were infiltrating into the deep dermis and atypical cells were observed along with the characteristics of SCAP.

Uncommonly, SCAP had a tubular dermal component or tubular apocrine adenoma. However, in contrast with the dermal component of SCACP, dermal tumor cells in our case were arranged with varying sizes and shapes such as strand, cord, or angular shapes. Also, dermal component was horizontally oriented as was the case for most malignant neoplasms.

In three previous cases (3, 6, 7), since the basement membrane of these papillations was intact and there was no involvement of the dermis, the specimens were diagnosed as SCACP in situ.

Cuataneous metastases from breast or gastrointestinal cancers should be differentiated from SCACP (4). They lack papillary structures containing deep invaginations as seen in SCACP. Metastatic thyroid carcinoma and hidradenoma papilliferum should also be included in the differential diagnosis due to their papillary structures (8).

Immunohistochemical and histochemical features of SCACP have been reported in 3 cases (5-7). Positive reactions to diastase-resistance periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) and cytokeratin were observed in all 3 cases and immunoreactivities to CEA showed positive reactions in 2 cases (5, 7). Ishida et al. (6) reported negativity to GCDFP-15 and CEA, and loss of immunoreactivities to CEA and GCDFP-15 in SCACP might be associated with its malignant de-differentiation in comparision with SCAP; however, Arai et al. (7) observed immunoreactivities to CEA and GCDFP-15 and stated that the loss of immunoreactivities to CEA and GCDFP-15 were not associated with the malignant de-differentiation. GCDFP-15 may be positive in both apocrine and eccrine units (9). HMFG-1 is positive in normal apocrine gland and tumors with apocrine differentiation (10). Therefore, HMFG-1 is thought to be a marker for apocrine differentiation in skin neoplasms (10). Positivity for GCDFP-15 and negativity for CEA and HMFG-1 were observed in our case.

The histogenesis of SCAP and SCACP is controversial. However, the differentiaton of apocrine glands is recently supported by following findings: decapitation is shown on the luminal surface of inner layer cells; the tumor is connected to folliculosebaceous structures; and there is apocrine glands in the underlying tissues (2, 7). In our case, decapitation and cystic invagination from the infundibular structure support the hypothesis that SCACP originates from apocrine glands.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download