Abstract

Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors (IMTs) are benign neoplasms that can occur at different anatomic sites with nonspecific clinical symptoms. A 48-yr-old woman presented with a 2-month history of a relapsed oral ulcer, progressive dyspnea, and a thoracic pain induced by breathing. A tumorous mass was noticed in the right costodiaphragmatic recess on chest computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging, and the patient underwent a right costotransversectomy with excision of the tumor, which originated from the 12th intercostal nerve. Histology and immunohistochemistry showed that the tumor was an IMT of the intercostal nerve. The patient's postoperative course was not favorable; dyspnea persisted after surgery, and a progressive pulmonary compromise developed. The cause of the respiratory failure was found to be bronchiolitis obliterans, which in this case proved to be a fatal complication of paraneoplastic pemphigus associated with an IMT. This case of IMT of the spinal nerve in the paravertebral region is unique in terms of its location and presentation in combination with paraneoplastic pemphigus, which is rare. A brief review of the heterogeneous theories concerning the pathogenesis, clinicopathological features, and differential diagnosis of this disease entity is presented.

Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors (IMTs) are benign tumor-like lesions of unknown etiology that can occur at different anatomic sites and have variable non-specific clinical symptoms. Moreover, this variability has led to a heterogeneous nomenclature. Plasma-cell granuloma, inflammatory pseudotumor, fibrous xanthoma, histiocytoma, and mast-cell granuloma are among the terms most frequently used as pathomorphologic descriptions (1). The common sites of this lesion are the lung (the originally described location), respiratory tract, gastrointestinal tract, orbit, liver, spleen, lymph nodes, heart, and brain (2, 3). Seven cases of intraspinal IMT have been reported (4, 5), and only five cases of IMT involving peripheral nerves have been previously described (6, 7). Although imaging techniques have made evident progress, they cannot be used for a preoperative diagnosis of IMT, and only histological examinations are capable of identifying its inflammatory character.

This paper describes an IMT of the intercostal nerve, a previously unreported location, in combination with paraneoplastic pemphigus (PNP), in a 48-yr-old woman, and includes a discussion of its clinicopathological features and diagnosis.

A 48-yr-old woman presented with a 1-month history of progressive dyspnea and pleuritic pain in the right lower chest, and also a thoracic back pain of 1-month duration. There was no history of trauma. She had a history of a chronic relapsing oral ulcer, and had been admitted to the Department of Internal Medicine at our institution 3 months earlier due to a fever and multiple oral ulcers (Fig. 1A), the latter of which had been diagnosed as pemphigus vulgaris by biopsy. However, unfortunately, several examinations failed to detect the exact origin of the fever. After discharge, she had been treated with prednisolone and azathiopurine for 3 months.

When she was readmitted, physical examination revealed an oral ulcer, multiple blisters and erythematous papules on trunk skin (Fig. 1B). All laboratory tests, including WBC count, RBC count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, and hemoglobin level were normal, as well as plain chest and spine radiographs. However, computed tomography (CT) with intravenous contrast visualized a clearly demarcated paraspinal mass with homogeneous enhancement in the right costodiaphragmatic recess (Fig. 2A). Magnetic resonance imaging showed an extradural and paraspinal ellipsoidal mass at the T12 level extending into the spinal foramen. Large vessels were present at the center of the mass (Fig. 2B). In view of her progressive symptoms, she was transferred to the Neurosurgery Department for further evaluation and treatment. Under the differential diagnosis for the mass including schwannoma, osteogenic sarcoma, chondrosarcoma, or metastasis, we approached via costotransversectomy and resected it completely. Intraoperatively, a well circumscribed tumor of 5×3×4 cm3 originating from the proximal part of the 12th intercostal nerve, but not infiltrating the nerve grossly, was found to be bulging into the right thoracic cavity. The mass was removed en-bloc with a portion of the parietal pleura. No involvement of any adjacent organ (lung, diaphragm, or vertebra) was found after complete excision. Biopsy specimens showed proliferation of a heterogeneous population of inflammatory cells, including macrophages, lymphocytes, and neutrophils with peripheral fibrosis (Fig. 3A). Immunohistochemically, all were negative for S100, leu7, and SMA, but positivity for CD3 and CD20 indicated the presence of both mature B and T lymphocytes. The final histological diagnosis was IMT.

Pleuritic pain improved progressively after surgery, but dyspnea persisted and a progressive pulmonary compromise developed. She was retransferred to the Department of Internal Medicine, and a repeat biopsy of an oral ulcer and direct tissue immunofluorescence showed intracellular IgG and complement C3 deposition within the epidermis (Fig. 3B). Finally, she was diagnosed as having PNP combined with bronchiolitis obliterans. She was continued on respiratory therapy and with prednisone, cyclosporine, and intravenous immunoglobulins. During the following months progressive dyspnea slightly improved after intravenous immunoglobulins therapy, as did the skin and mucosal lesion. However, 3 months after the operation she was readmitted to the intensive care unit for progressive dyspnea. Unfortunately methylprednisolone and cyclosporin was ineffective, and she died of pulmonary failure.

The clinicopathological features of IMTs described in the literature as originating from the peripheral nerve are summarized in Table 1. The present case, an IMT that originated from the intercostal nerve in the paravertebral region, is unique in terms of its location. IMTs are typically composed of variable amounts of stromal and cellular elements, and myofibroblasts, which are involved in tissue repair, are now recognized as the principal cell type (4, 8). The precise etiology of IMT is unknown. In some cases, they are considered to result from inflammation following minor trauma or surgery or to be associated with another malignancy (9, 10). Some authors believe that this tumor is a low-grade fibrosarcoma that contains inflammatory (lymphomatous) cells. Immunohistochemical studies of T- and B-cell subpopulations may be helpful for differentiating IMT and lymphoma. An immune-autoimmune mechanism has also been implicated for the etiology of IMT. Many of the features of IMTs can be related to the production of inflammatory mediators, such as cytokines, particularly interleukin-1 (11). Locally, IMTs stimulate the proliferation of fibroblasts, the extravasation of neutrophils, and the activation and elevation of vascular endothelium procoagulant activity (12).

Complete surgical resection, if possible, is the treatment of choice for most IMTs, with the exception of orbital lesions (13-16), and this approach may be successful in cases of recurrence. Meanwhile, some authors have reported spontaneous regression (17, 18), and successful radiation therapy in unresectable cases. Chemotherapy has also been used, but generally had had minimal effect, and although response to steroids is often unpredictable, they remain the primary treatment method for orbital IMT.

Our patient developed progressive airflow obstruction induced by undiagnosed PNP and this resulted in respiratory failure. PNP (19, 20) is an autoantibody-mediated mucocutaneous blistering disease, which is associated with underlying neoplasms (hematologic-related neoplasms, sarcoma, and benign tumors such as Castleman tumors and IMT). Since PNP was first described in 1990 by Anhalt et al. (21), approximately 60 cases have been reported, and the diagnostic criteria include clinical findings, histologic, direct immunofluorescence (DIF), indirect immunofluorescence (IIF), and immunoprecipitation test. The criteria were later revised by Camisa and Helm (22) and divided into major and minor signs. Major signs are polymorphic mucocutaneous eruption, concurrent internal neoplasia, and serum immunoprecipitation with a complex of four proteins (desmoplakin I, BP Ag, envoplakin and desmoplakin II, and periplakin), whereas minor signs include histologic evidence of acantholysis in erythematous lichenoid papules, DIF findings of basement membrane and intercellular epidermal IgG and C3, and IIF staining of the rat bladder epithelium. Three major signs, or two major and two minor signs are required to diagnose PNP.

Several cases of PNP, including one case of IMT, which resulted in respiratory failure caused by airway obliteration, have been reported (19, 20). Moreover, after the onset of respiratory failure, autoantibody reaction against plakins detected by serum immunoprecipitation at the onset of PNP, disappeared as determined by immunofluorescence of the bronchial epithelium. Based on the above-mentioned findings, it is postulated that autoantibodies against some of these antigens play a causative role in acute respiratory epithelial inflammation (20). Moreover, when treating PNP the lethal complication of bronchiolitis obliterans should be kept in mind. Furthermore, the prevention of autoantibody-mediated injury to the respiratory epithelium should be an important treatment goal. Early diagnosis and tumor removal before respiratory involvement are essential because of the typically poor response to immunosuppressive therapy shown in PNP.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

(A) Erosions of the vermilion border, tongue, and buccal mucosa. (B) Multiple erythematous papules on trunk skin.

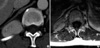

Fig. 2

(A) Contrast-enhance abdominal CT revealing a solitary paraspinal soft tissue mass with homogeneous attenuation in the posterior aspect of the right hemithorax. The mass displaced the right lower lobe superiorly. (B) Enhanced T1-weighted magnetic resonance axial section through the disc at T12-L1 showing the mass and its large vessels. Vertebra and ribs were not eroded, and adjacent organs (liver, diaphragm, and thecal sac) were not involved by the mass.

Fig. 3

Histology of tumor samples resected during operation. (A) Photomicrograph showing an admixture of spindle-shaped ovoid cells and a conspicuous admixture of lymphocytes and plasma cells (H&E, ×400). (B) Direct immunofluorescence showed IgG deposits in the basement membrane zone and epithelial layer in this biopsy specimen of ulcerated oral mucosa.

References

1. Narla LD, Newman B, Spottswood SS, Narla S, Kolli R. Inflammatory pseudotumor. Radiographics. 2003. 23:719–729.

2. Anthony PP. Inflammatory pseudotumour (plasma cell granuloma) of lung, liver and other organs. Histopathology. 1993. 23:501–503.

3. Dehner LP. The enigmatic inflammatory pseudotumors: the current state of our understanding, or misunderstanding (editorial). J Pathol. 2000. 192:277–279.

4. Despeyroux-Ewers M, Catalaa I, Collin L, Cognard C, Loubes-Lacroix F, Manelfe C. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumour of the spinal cord: case report and review of the literature. Neuroradiology. 2003. 45:812–817.

5. Kim YO, Cho YJ, Ahn SK, Hwang JH, Ahn MS, Choi YH. Inflammatory pseudotumor of the thoracic spinal cord meninges: A case report. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 1998. 27:1419–1423.

6. Perez-Lopez C, Gutierrez M, Isla A. Inflammatory pseudotumor of the median nerve: case report and review of the literature. J Neurosurg. 2001. 95:124–128.

7. Weiland TL, Scheithauer BW, Rock MG, Sargent JM. Inflammatory pseudotumor of nerve. Am J Surg Pathol. 1996. 20:1212–1218.

8. Mountney J, Suvarna SK, Brown PW, Thorpe JA. Inflammatory pseudotumour of the lung mimicking thymoma. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 1997. 12:801–803.

9. Maves CK, Johnson JF, Bove K, Malott RL. Gastric inflammatory pseudotumor in children. Radiology. 1989. 173:381–383.

10. Sanders BM, West KW, Gingalewski C, Engum S, Davis M, Grosfeld JL. Inflammatory pseudotumor of the alimentary tract: clinical and surgical experience. J Pediatr Surg. 2001. 36:169–173.

11. Hytiroglou P, Brandwein MS, Stauchen JA, Mirante JP, Urken ML, Biller HF. Inflammatory pseudotumor of the parapharyngeal space: case report and review of the literature. Head Neck. 1992. 14:230–234.

12. Coffin CM, Watterson J, Priest JR, Dechner LP. Extrapulmonary inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor (inflammatory pseudotumor): a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 84 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1995. 19:859–872.

13. Jenkins PC, Dickison AE, Flanagan MF. Cardiac inflammatory pseudotumor: rapid appearance in an infant with congenital heart disease. Pediatr Cardiol. 1996. 17:399–401.

14. Martin CJ. Orbital pseudotumor: case report and overview. J Am Optom Assoc. 1997. 68:775–781.

15. Rose AG, McCormick S, Cooper K, Titus JL. Inflammatory pseudotumor (plasma cell granuloma) of the heart. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1996. 120:549–554.

16. Scott L, Blair G, Taylor G, Dimmick J, Fraser G. Inflammatory pseudotumors in children. J Pediatr Surg. 1988. 23:755–758.

17. Maier HC, Sommers SC. Recurrent and metastatic pulmonary fibrous histiocytoma/plasma cell granuloma in a child. Cancer. 1987. 60:1073–1076.

18. Pearson PJ, Smithson WA, Driscoll DJ, Banks PM, Ehman RL. Inoperable plasma cell granuloma of the heart: spontaneous decrease in size during an 11-month period. Mayo Clin Proc. 1998. 63:1022–1025.

19. Mar WA, Glaesser R, Struble K, Stephens-Groff S, Bangert J, Hansen RC. Paraneoplastic pemphigus with bronchiolitis obliterans in a child. Pediatr Dermatol. 2003. 20:238–242.

20. Takahashi M, Shimatsu Y, Kazama T, Kimura K, Otsuka T, Hashimoto T. paraneoplastic pemphigus associated with bronchiolitis obliterans. Chest. 2000. 117:603–607.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download