Abstract

Variceal bleeding from enterostomy site is an unusual complication of portal hypertension. The bleeding, however, is often recurrent and may be fatal. The hemorrhage can be managed with local measures in most patients, but when these fail, surgical interventions or portosystemic shunt may be required. Herein, we report a case in which recurrent bleeding from stomal varices, developed after a colectomy for rectal cancer, was successfully treated by placement of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) with coil embolization. Although several treatment options are available for this entity, we consider that TIPS with coil embolization offers minimally invasive and definitive treatment.

Patients with surgically created intestinal anastomosis or stoma can be complicated by stomal varices from portal hypertension (1). Typical sites of variceal formation include the esophagus and the stomach. Moreover, "ectopic" varices may occur at any point along the entire gastro-intestinal tract such as duodenum, jejunum, ileum, colon, rectum, or other sites (2).

A definite consensus on the best treatment option for ectopic variceal bleeding from stoma sites has not been proposed. Therapeutic options for an ectopic variceal bleeding from stoma sites include suture ligation (3), sclerotherapy (4), angiographic embolization (1), revision of stoma (5), and ultimately liver transplantation. Local measures are often effective in initial hemostasis, however, the bleeding may recur (6, 7). Surgical measures include portosystemic shunt application, either by classic surgical shunt (Warren-Shunt) or by transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) (8). TIPS is currently considered to be the treatment of choice for stomal varices with liver cirrhosis and portal hypertension (5, 8).

To the best of our knowledge, there is no published report on the result of TIPS in patients with stomal variceal bleeding in Korea. Therefore, we report a case of 63-yr old male patient with prior Mile's operation for rectal cancer in whom recurrent bleeding from stomal varices was successfully treated by the combination of TIPS and coil embolization.

A 63-yr-old man with alcoholic liver cirrhosis visited the emergency room of our hospital due to bleeding from stomal varices. He had undergone Mile's operation for rectal cancer six years before. Alcoholic liver cirrhosis was diagnosed at the time of operation. After the surgery, the patient developed stomal varices, which bled on multiple occasions over a 4-yr period, requiring repeated blood transfusions. Recently, the bleeding was noted, occurring once every two or three weeks. Conservative measures including local compression, intravenous fluids, and blood transfusions were used to control the bleedings. On admission, his blood pressure was 60/40 mmHg, and pulse rate was 52 per minute. Physical examination showed semicomatous mental state, severely pale conjunctivae, and a large amount of ascites. There was a left-sided colostomy site on the abdomen. The bleeding was noted on the muco-cutaneous junction of the colostomy site with fresh blood in the stomal appliance, and there was no evidence of bleeding from the upper gastrointestinal tracts. The hemoglobin was 2.6 g/dL and platelets 103,000/µL. The albumin was 0.7 g/dL, total bilirubin 0.9 mg/dL, aspartate aminotransferase 30 IU/L, alanine aminotransferase 16 IU/L, γ-Glutamyltransferase 6 IU/L, prothrombin time 25.9 sec with international normalized ratio (INR) 3.1, activated partial thromboplastin time >120 sec, blood urea nitrogen 23.4 mg/dL, and creatinine was 1.4 mg/dL. The Child-Pugh class was C. The patient was diagnosed with hypovolemic shock and was treated with blood transfusions and cardiopulmonary resuscitation resulting in complete recovery.

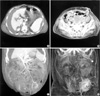

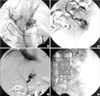

An esophagogastroduodenoscopic examination revealed esophageal varices (Fig. 1A). On sonographic examination of the abdomen, cirrhotic liver with a large amount of ascites was noted. Abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan with a 16-channel multidetector unit showed engorged veins along the wall of the stoma, which were tributaries of dilated inferior mesenteric vein (Fig. 2A, B). The direct volume rendering and maximum intensity projection images confirmed unusual portosystemic collaterals through the muco-cutaneous junction of the stoma. There were dilated veins in the abdominal wall around the stoma as well (Fig. 2C, D).

During the first two weeks of hospitalization, the patient had three episodes of stomal variceal bleeds. Local therapeutic measures such as direct compression and suture ligation of the bleeder failed to control the recurrent bleeding. He continued to have symptoms of faintness and shortness of breath, and required multiple blood transfusions.

On 16th day, TIPS with coil embolization was performed. Direct portogram showed prominent gastroesophageal varices (Fig. 3A). There was retrograde flow of contrast dye through the stoma into the collateral veins of abdominal wall on a selective inferior mesenteric venogram (Fig. 3B). To control the variceal bleeding, the inferior mesenteric vein, the feeder of varices, was embolized with 9 stainless-steel coils (diameter 8 mm, length 5 cm). Subsequently, the TIPS tract was dilated with a balloon catheter (diameter 10 mm, length 4 cm). And a metallic wall stent (diameter 10 mm, length 9 cm) was placed in the tract (Fig. 3C). Final portogram showed a much decreased flow through the gastroesphageal varices. Selective inferior mesenteric venogram also showed collapsed lumen and the disappearance of retrograde flow (Fig. 3D). Previously noted esophageal varices disappeared on the follow-up esophagogastroduodenoscopy on 4 days after TIPS (Fig. 1B). After the TIPS/coil embolization, the patient had two mild episodes of hepatic encephalopathy, but fully recovered with conservative treatment during the rest of hospitalization, and was discharged from the hospital in good condition on 48th day.

At 6 months follow-up, the patient remained well without further episodes of stomal bleeding and hepatic encephalopathy.

Stomal variceal bleeding is a rare and serious complication of portal hypertension. Since the original description by Resnick et al. (9) in 1968, fewer than 100 cases have been reported (6, 7), and fewer than 20 patients with stomal variceal bleeding have been treated with TIPS in the English literature (2, 10-12).

Bleeding from stomal varices occur in up to 27 percent of patients with chronic liver failure who had a permanent stoma (6). In a review of 10 cases of colostomy-associated variceal bleeding by Conte et al. (7), the average time from the colostomy formation to the first stomal bleed was 23 months (range, 6 to 84 months). Despite the low mortality (3 to 4 percent per episode of bleeding), the overall morbidity of the stomal varices is much higher given the propensity for recurrence, often massive bleeding, necessitating multiple blood transfusions (1, 13).

Most of the stomal varices arise at the border of the mucocutaneous junction of the stoma. The stomal varices are a result of spontaneous anastomoses between the high-pressured portal circulation and the relatively low-pressured systemic venous system. Spontaneous bleeding may occur from variceal erosions or from local trauma (14).

Until now, an optimal treatment modality for stomal variceal bleeding has not been established yet. The liver transplantation is a definite treatment of the recurrent stomal variceal bleeding with decompensated liver cirrhosis, but liver transplantation was not feasible in this patient because of the patient's low socioeconomic status. Local compression and suture ligation are ineffective for the control of recurrent bleeding (4, 7). Injection sclerotherapy is effective in controlling acute stomal variceal bleeding (4), but is not so effective as shunt surgery in preventing rebleeding or improving survival in patients with chronic and recurrent bleedings that require repeated multple transfusions. In cases of acute bleeding refractory to sclerotherapy deemed to be at an extreme risk for shunt surgery, percutaneous transhepatic embolization has been used successfully (1, 14).

Many of the treatments targeted to the local control of the stomal variceal bleed described may have the unattended consequence of diverting the blood flow to other areas such as the gastroesophageal junction. This diversion of the blood flow to the gastroesophageal junction can result in esophageal varices (15, 16). Moreover, the local treatments have a high rate of recurrent bleeding (13, 15-19). Hence, a durable shunt procedure is an attractive alternative therapy that will decompress the portal system, prevent recurrent bleeding, and new variceal formations elsewhere. The shunt method has been shown to control stomal variceal hemorrhage (13, 19). However, the surgical shunt procedure may be associated with higher mortality compared to the stomal variceal bleeding itself. TIPS has proven to be an effective alternative in the management of esophageal and gastric variceal bleeding, and is associated with significantly less morbidity and mortality than a surgical shunt procedure (20, 21).

However, patients with severe decompensated liver function may result in a higher mortality due to encephalopathy than the stomal variceal bleeding itself (14). Hence, cautious application of the TIPS procedure in patients with stomal variceal bleed should be taken. It was reported that the percutaneous transhepatic coil embolization was effective in controlling stomal variceal bleeding with decompensated liver function (14).

There are three major concerns on the use of TIPS in the treatment of stomal variceal bleeding: 1) the long-term patency of TIPS tract; 2) the risk of hepatic encephalopathy; and 3) the survival benefit.

The reocclusion rate of the TIPS may vary depending on the situation and the reocclusion could be managed by repeat TIPS or balloon dilatation of the occluded stent lumen (10). The patency of the TIPS has been reported to be 5 to 48 months in the literature (10-12).

Our patient experienced two mild episodes of hepatic encephalopathy after the TIPS procedure and fully recovered with conservative treatments. There has been no recurrence of the hepatic encephalopathy and stomal variceal bleeding at 6 months follow-up. Some authors (18) argue that the shunting procedure may control the stomal variceal bleeding, but the procedure does not increase the survival and unnecessarily expose the patients to the risk of encephalopathy. In our patient, a clinically significant hepatic dysfunction has not been observed after the placement of TIPS and coil embolization. If the patient experiences a recurrent hepatic encephalopathy after TIPS and coil embolization, the shunt occlusion procedure may be considered. It was reported that only the percutaneous transhepatic coil embolization without TIPS was effective in controlling stomal variceal bleeding with decompensated liver function (14). We performed percutaneous transhepatic coil embolization in our case, so even if the shunt may be occluded, it will be effective in controlling recurrent stomal variceal bleeding.

We consider the combination of TIPS and coil embolization is the most effective and safe treatment modality for recurrent stomal variceal bleeding as in our case. However, further studies with more cases are warranted to evaluate the efficacy, survival benefit, and potential long-term complications of TIPS.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 1Esophageal varices are noted in esophagogastroduodenoscopy before transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS). (A) After TIPS, the esophageal varices are disappeared in esophagogastroduodenoscopy (B). |

| Fig. 2Axial scans of portal phase computed tomography (A, B) show gastroesophageal varices and findings of liver cirrhosis with a large amount of ascites. There are dilated venous structures along the wall of the stoma (arrowhead). The maximum intensity projection image (C) and direct volume rendering image (D) confirm unusual portosystemic collateral through the mucocutaneous junction of the stoma. Dilated draining veins of abdominal wall are noted (arrows). |

| Fig. 3On direct portogram, (A) there are prominent gastroesophageal varices. Retrograde flow of contrast dye through the stoma into the collateral veins of abdominal wall on selective inferior mesenteric venogram (B). The transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) tract is dilated with a balloon catheter, and a metallic stent is placed in the tract (C). Selective inferior mesenteric vein venography obtained after coil embolization and creation of TIPS show collapsed lumen and disappearance of retrograded flow (D). |

References

1. Samaraweera RN, Widrich WC, Waltman A, Steinberg F, Greenfield A, Srinivasan M, Robbins AH, Johnson WC. Stomal varices: Percutaneous transhepatic embolization. Radiology. 1989. 170:779–782.

2. Vangeli M, Patch D, Terreni N, Tibballs J, Watkinson A, Davies N, Burroughs AK. Bleeding ectopic varices-treatment with transjugular intrahepatic porto-systemic shunt (TIPS) and embilization. J Hepatol. 2004. 41:560–566.

3. Hollands MJ. Parastomal haemorrhage from an ileal conduit secondary to portal hypertension. Br J Surg. 1982. 69:675.

4. Wolfsen HC, Kozarek RA, Bredfeldt JE, Fenster LF, Brubacher LL. The role of endoscopic injection sclerotherapy in the management of bleeding peristomal varices. Gastrointest Endosc. 1990. 36:472–474.

5. Uemoto S, Martin AJ, Fleming W, Habib NA. The use of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt and surgical portocaval H-shunt for the treatment of colorectal variceal bleeding. Hepatogastroenterology. 1995. 42:557–560.

6. Fucini C, Wolff BG, Dozois RR. Bleeding from peristomal varices: perspectives on prevention and treatment. Dis Colon Rectum. 1991. 34:1073–1078.

7. Conte JV, Arcomano TA, Naficy MA, Holt RW. Treatment of bleeding stomal varices: report of a case and review of the literature. Dis Colon Rectum. 1990. 33:308–314.

8. Shibata D, Brophy DP, Gordon FD, Anastopulos HT, Sentovich SM, Bleday R. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt for treatment of bleeding ectopic varices with portal hypertension. Dis Colon Rectum. 1999. 42:1581–1585.

9. Resnick RH, Ishihara A, Chalmers TC, Schimmel EM. A controlled trial of colon bypass in chronic hepatic encephalopathy. Gastroenterology. 1968. 54:1057–1069.

10. Alkari B, Shaath NM, El-Dhuwaib Y, Aboutwerat A, Warnes TW, Chalmers N, Ammori BJ. Transjugular intrahepatic porto-systemic shunt and variceal embolisation in the management of bleeding stomal varices. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2005. 20:457–462.

11. Morris CS, Najarian KE. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt for bleeding stomal varices associated with chronic portal vein occlusion: long-term angiographic, hemodynamic, and clinical follow-up. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000. 95:2966–2968.

12. Ryu RK, Nemcek AA Jr, Chrisman HB, Saker MB, Blei A, Omary RA, Vogelzang RL. Treatment of stomal variceal hemorrhage with TIPS: case report and review of the literature. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2000. 23:301–303.

13. Ackerman NB, Graeber GM, Fey J. Enterostomal varices secondary to portal hypertension: progression of disease in conservatively managed cases. Arch Surg. 1980. 115:1454–1455.

14. Kishimoto K, Hara A, Arita T, Tsukamoto K, Matsui N, Kaneyuki T, Matsunaga N. Stomal varices: treatment by percutaneous transhepatic coil embolization. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 1999. 22:523–525.

15. Cameron AD, Fone DJ. Portal hypertension and bleeding ileal varices after colectomy and ileostomy for chronic ulcerative colitis. Gut. 1970. 11:755–759.

16. Adson MA, Fulton RE. The ileal stoma and portal hypertension: an uncommon site of variceal bleeding. Arch Surg. 1977. 112:501–504.

17. Wong RC, Berg CL. Portal hypertensive stomapathy: a newly described entity and its successful treatment by placement of a transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997. 92:1056–1057.

18. Grundfest-Broniatowski S, Fazio V. Conservative treatment of bleeding stomal varices. Arch Surg. 1983. 118:981–985.

19. Ricci RL, Lee KR, Greenberger NJ. Chronic gastrointestinal bleeding from ileal varices after total proctocolectomy for ulcerative colitis: correction by mesocaval shunt. Gastroenterology. 1980. 78:1053–1058.

20. Rossle M, Haag K, Ochs A, Sellinger M, Noldge G, Perarnau JM, Berger E, Blum U, Gabelmann A, Hauenstein K, Langer M, Gerok W. The transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic stent-shunt procedure for variceal bleeding. N Engl J Med. 1994. 330:165–171.

21. Johnson PA, Laurin J. Transjugular portosystemic shunt for treatment of bleeding stomal varices. Dig Dis Sci. 1997. 42:440–442.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download