Abstract

Intramuscular hemangioma, an infrequent but important cause of musculoskeletal pain, is often difficult to establish the diagnosis clinically. This report describes a case of a 32-yr-old woman who presented with severe left calf pain for 10 yr. Initial conservative treatments consisting of intramuscular electrical stimulation, herb medication, acupuncture, and intramuscular lidocaine injection under the diagnosis of myofascial pain syndrome in other facilities, failed to alleviate the symptoms. On physical examination, there was no motor weakness or sensory change. Conventional radiography of the leg revealed a soft tissue phlebolith. Conventional angiography study showed hemangioma. Intramuscular hemangioma within the soleus muscle was confirmed by magnetic resonance imaging. Following surgical excision of the hemangioma, the patient's symptom resolved completely. Intramuscular hemangioma is a rare cause of calf pain and should be considered in the differential diagnosis if a patient with muscle pain, particularly if associated with a soft tissue mass, fails to respond to conservative treatment.

Calf pain is a common problem in the clinical field and is

caused by many various conditions. Soft-tissue etiologies include rupture of the gastrocnemius muscle, muscle strain, and myofascial pain syndrome (MPS) of calf muscles, which are all relatively easy to establish the diagnosis and usually resolve with appropriate treatment (1, 2). Among these, the common cause of calf pain in clinical practice is MPS of gastrocnemius and/or soleus muscles (3, 4).

More serious causes are acute or chronic osteomyelitis, peripheral arterial diseases, or peripheral venous diseases (3). As a rare etiology, sural nerve entrapment may also cause chronic calf pain (5). It is very important to find the actual cause in order to relieve the patient's pain and lessen the effort, time, and money consumed in the workup and management of a patient with severe calf pain.

Intramuscular hemangioma, an infrequent but important cause of musculoskeletal pain, is often difficult to diagnose clinically. The following report demonstrates the importance of considering intramuscular hemangioma in the differential diagnosis of calf pain and discusses the use of surgical excision biopsy for its treatment.

A 32-yr-old woman with no relevant or significant medical history presented with severe left calf pain that had persisted for the past 10 yr. The symptom was constant and worsened with menstruation, standing or walking for more than 30 min. The pain was relieved by elevating the leg in the sitting position or massaging the calf muscles. The pain was not associated with any progressive neurologic symptoms or signs. She reported that none of the medications she had tried provided any significant pain relief. Intramuscular electrical stimulation for 4 months and repeated muscle injections with lidocaine were also ineffective. Alternative treatments including acupuncture and Korean herbal medications had been tried many times without much success.

The patient's pain drawing showed a pain pattern limited to the left calf, especially in the medial side, which indicated a referred pain pattern of medial gastrocnemius or soleus muscle (Fig. 1). Physical examination revealed severe tenderness on the medial side of the left calf muscles. Signs of calf swelling were equivocal. Deep tendon reflexes were normal in both sides. Muscle strength of both lower extremities was normal. Sensation in both lower extremities was intact. The straight leg raising test was normal. Conventional radiography of the left leg showed several mottled calcifications within the muscles but did not reveal erosions of tibia or fibula (Fig. 2A). To rule out a possible vascular deformity, femoral angiography was performed and a hemangioma was suggested in the left calf (Fig. 2B). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the left lower extremity was performed for further evaluation of these abnormalities and showed an enhancing soft-tissue mass in the medial aspect of the soleus muscle (Fig. 2C, D).

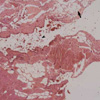

The patient was referred to an orthopedic surgeon and underwent excisional biopsy. Operative findings revealed a mass consisting of several irregular fragments of muscular soft tissue, measuring 6×6×4 cm. The final pathologic diagnosis was intramuscular hemangioma with fatty overgrowth isolated to the soleus muscle, which was in concordance with the MRI findings (Fig. 3). Within 1 month, the patient reported 90% pain relief and had discontinued all pain medications. Even with prolonged walking of more than 30 min, calf pain did not occur and the subject was able to resume mountain hiking 3 months following the operation.

Hemangiomas comprise 7% of all benign tumors (6), and are most commonly superficial and easy to establish the diagnosis clinically. However, deep-seated hemangiomas such as intramuscular hemangiomas are relatively uncommon (6, 7), and often pose diagnostic difficulties (8, 9). Age of occurrence of intramuscular hemangioma is most common in the third and forth decades, but occasionally may present earlier (10, 11). Although intramuscular hemangioma have a wide anatomical distribution, it most commonly occurs in the extremities, and all patients present with a growing palpable mass, which may or may not be accompanied by pain or may present as pain without a mass (10, 12-15).

For the diagnosis of intramuscular hemangioma, plain radiographs, MRI, angiography, and positron emission tomography (PET) may be helpful. Plain radiographs show phleboliths, particularly phleboliths associated with a soft-tissue mass and cortical or periosteal reaction adjacent to a soft-tissue hemangioma (16). MRI is useful in defining the location and extent of intramuscular hemangiomas and is now routinely used to characterize intramuscular hemangiomas (10). Angiography of a peripheral hemangioma is especially useful for evaluating the extent and degree of vascularity, and vascular supply (17). 18F-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose (FDG)-PET and fluorine-18 alpha-methyltryosine (FMT)-PET may be useful in the diagnostic workup of hemangioma as well as for differentiation from malignancy (11). Intramuscular hemangiomas that are well localized within a single muscle group, contain thromboses, or are located in specialized muscle groups (such as the instrinsic muscles of the hand), and those causing neurologic impairment or compression syndrome, require surgical excision (18). Although local recurrence is reported to be over 50%, it has no correlation with a predominant vessel type or anatomical localization, and there have been no reports of malignant degeneration or metastasis, which is possible in cases of incomplete excision (6, 19).

In our case, it took 10 yr to establish the correct diagnosis of the intramuscular hemangioma. Pain drawing was suggestive of the pain pattern of MPS in medial gastrocnemius or soleus muscle. Physical examination revealed severe tenderness in the calf, but no palpable mass. Such vague symptoms and signs lead to the misdiagnosis of MPS and inappropriate treatments by many health care providers. However, upon our diagnosis of a well-circumscribed intramuscular hemangioma within the soleus muscle, local excision was successful in obliterating the patient's symptoms and signs.

In conclusion, this case demonstrates that when a patient presents with a painful soft tissue mass of the leg, severe intractable calf pain, or when muscle pain fails to respond to conservative treatment, intramuscular hemangioma or other soft tissue tumors should be included in the differential diagnosis. The appropriate imaging and consultations should be performed, in order to arrive at the correct diagnosis and management, accordingly.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 2(A) Plain radiography of the left leg shows several focal round calcifications within the muscles. (B) Femoral angiography reveals faint tissue staining and puddlings with early venous drainage that suggest vascular malformation on the left calf. (C, D) Sagittal and axial views of magnetic resonance image shows findings consistent with an intramuscular hemangioma involving the medial potion of the soleus muscle. |

References

1. Prateepavanich P, Kupniratsaikul V, Charoensak T. The relationship between myofascial trigger points of gastrocnemius muscle and nocturnal calf cramps. J Med Assoc Thai. 1999. 82:541–549.

2. Travell JG, Simons DG. Myofascial pain and dysfunction. 1992. Volum 2:first edition. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins.

3. Bonica JJ, Sola AE. Bonica JJ, editor. Other painful disorders of the lower limbs. The management of pain. 1990. second edition. Malvern: Lea & Febiger;1621–1634.

4. Walsh NE, Dumitru D, Schoenfeld LS, Ramamurthy S. Delisa JA, editor. Treatment of the patient with chronic pain. Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation: Principles and practice. 2005. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins;493–529.

5. Fabre T, Montero C, Gaujard E, Gervais-Dellion F, Durandeau A. Chronic calf pain in athletes due to sural nerve entrapment. A report of 18 cases. Am J Sports Med. 2000. 28:679–682.

6. Enzinger FM, Weiss SW. Enzinger FM, Weiss SW, editors. Benign tumors and tumorlike lesions of blood vessels. Soft tissue tumors. 1995. third ed. St Louis: Mosby;579–626.

7. Engelstad BL, Gilula LA, Kyriakos M. Ossified skeletal muscle hemangioma: radiologic and pathologic features. Skeletal Radiol. 1980. 5:35–40.

8. Greenspan A, McGahan J, Vogelsang P, Szabo RM. Imaging strategies in the evaluation of soft tissue hemangiomas of the extremities: correlation of the findings of plain radiography, angiography, CT, MRI, and ultrasonography in 12 histologically proven cases. Skeletal Radiol. 1992. 21:11–18.

9. Hawnaur JM, Whitehouse RW, Jenkins JP, Isherwood I. Musculoskeletal haemangiomas: comparison of MRI with CT. Skeletal Radiol. 1990. 19:251–258.

10. Kim EY, Ahn JM, Yoon HK, Suh YL, Do YS, Kim SH, Choo SW, Shoo IW, Kim SM, Kang HS. Intramuscular vascular malformations of an extremity: findings on MR imaging and pathologic correlation. Skeletal Radiol. 1999. 28:515–521.

11. Hatayama K, Watanabe H, Ahmed AR, Yanagawa T, Shinozaki T, Oriuchi N, Aoki J, Takeuchi K, Endo K, Takagishi K. Evaluation of hemangioma by positron emission tomography: role in a multimodality approach. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2003. 27:70–77.

13. Conners JJ, Khan G. Hemangiomas of striated muscle. South Med J. 1977. 70:1423–1424.

14. Kim SH, Shin HH, Rho BK, Lee ES, Baek SH. A case of intramuscular hemangioma presenting with large-angle hypertropia. Korean J Ophthalmol. 2006. 20:195–198.

15. Wu JL, Wu CC, Wang SJ, Chen YJ, Huang GS, Wu SS. Imaging strategies in intramuscular haemangiomas: an analysis of 20 cases. Int Orthop. 2006. Oct. 05. [Epub ahead of print].

16. Sung MS, Kang HS, Lee HG. Regional bone changes in deep soft tissue hemangioma: radiographic and MR features. Skeletal Radiol. 1998. 27:205–210.

17. Levin DC, Gordon DH, McSweeney J. Arteriography of peripheral hemangiomas. Radiology. 1976. 121:625–630.

18. Hein KD, Mulliken JB, Kozakewich HP, Upton J, Burrows PE. Venous malformations fo skeletal muscle. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002. 110:1625–1635.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download