Abstract

Benign schwannomas arise in neural crest-derived Schwann cells. They can occur almost anywhere in the body, but their most common locations are the central nervous system, extremities, neck, mediastinum, and retroperitoneum. Schwannomas occurring in the biliary tract are extremely rare and mostly present with obstructive jaundice. We recently experienced a case of extrahepatic biliary schwannomas in a 64-yr-old female patient who presented with intra- and extrahepatic bile duct and gallbladder stones during a screening program. To the best of our knowledge, extrahepatic biliary schwannomas associated with bile duct stones have not been reported previously in the literature.

A ductal adenocarcinoma is the most common tumor developing from the extrahepatic bile duct (1). Benign tumors of the extrahepatic biliary duct are extremely rare, and include adenomas and tumors of the supporting structures such as leiomyomas, lipomas, carcinoids, and fibromas. These tumors are almost indistinguishable from malignant tumors and need to be resected. Schwannomas occurring in the soft tissues of the head and neck, extremities and retroperitoneum can also develop in the extrahepatic biliary duct due to the abundant anastomotic network of sympathetic and parasympathetic nerve fibers and blood vessels from branches of the hepatic and gastroduodenal arteries (2). However, there have been very few case reports in the literature.

We describe the first case of schwannomas arising in the extrahepatic bile duct in Korea, which presented as intra- and extrahepatic bile duct and gallbladder stones.

A 64-yr-old female patient was referred for a surgery for intrahepatic duct and gallbladder stones detected on a screening program. She had no previous history of any other major illness. Her vital signs were as follows: blood pressure, 140/ 70 mmHg; pulse rate, 72/min; respiratory rate, 22/min; and body temperature, 36℃. There was no evidence of jaundice or abdominal pain. The laboratory studies revealed: leukocyte count, 8,230/µL; hemoglobin, 15.7 g/dL; total protein, 7.0 g/dL; total albumin, 3.8 g/dL; total bilirubin, 0.6 mg/dL; direct bilirubin, 0.2 mg/dL; serum asparate aminotransferase, 19 IU/L; serum alanine aminotransferase 14 IU/L; serum lactate dehydrogenase 298 IU/L; serum alkaline phosphatase, 57 IU/L; and serum gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase, 51 IU/L. The tumor markers including CEA and CA 19-9 were within normal ranges. The abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan revealed that the intrahepatic bile ducts were slightly dilated and contained stones. The gallbladder was also filled with many small stones. However, the distal part of the common bile duct and pancreas were normal (Fig. 1). Endoscopic retrograde cholangiography revealed a threadlike stricture at the proximal part of the common bile duct and a dilatation of the upstream intra- and extrahepatic bile ducts with abundant stones. In addition, the gallbladder was filled with small stones, and the cystic duct was inserted aberrantly into the right intrahepatic bile duct (Fig. 2). Surgery was planned because it was believed the intrahepatic duct stones were caused by the stricture. Furthermore, it was difficult to differentiate between a malignant or benign stricture. The patient underwent surgery on the bile duct. The pathology findings of the surgical specimens showed several well-demarcated nodules in the bile ductal wall and an intact mucosal epithelium of the bile duct. The largest one measured approximately 1 cm in the largest dimension (Fig. 3A). Microscopically, the tumors were mainly composed of spindle-shaped cells arranged in short bundles or interlacing fascicles with nuclear palisading (Fig. 3B, C). Immunohistochemically, the tumor cells were stained strongly for the S-100 protein (Fig. 3D), but were negative for CD 34, CD 117, and actin. The histological diagnosis was benign multinodular schwannomas of the extrahepatic bile duct. The postoperative course was uneventful, and the patient has been doing well without any complications.

Schwannomas are benign neurogenic tumors that arise in the nerve sheaths of the peripheral nerves in young to middle-aged adults. They can occur almost anywhere in the body but have a predilection for the head, the neck, and the flexure surfaces of the upper and low extremities. They can sometimes show secondary degenerative changes such as cyst formation, calcification, hemorrhage, and hyalinization (3). Clinically, these tumors are generally asymptomatic and are often discovered incidentally.

Schwannomas arising in the digestive tract are quite rare, and occur most commonly in the stomach, followed by the colon and rectum (4, 5). Schwannomas of the biliary tract can also develop because there is an abundant network of sympathetic and parasympathetic nerve fibers to the wall of the gallbladder and bile duct. However, schwannomas clinically arising in the biliary tract are extremely rare, and an extrahepatic bile ductal origin is the rarest. To our knowledge, only five cases of schwannomas involving the extrahepatic biliary duct have been reported (6-10). Clinical characteristics in of these five cases are shown in Table 1. The present case differs from previously reported biliary tract schwannomas in some clinicopathological features. First, it was found incidentally on health screenings while others mainly presented with obstructive jaundice. Secondly, the present tumor was shown to be associated with intra- and extrahepatic bile duct stones, which were grossly pigmented stones. It seemed that bile stasis resulting from mechanical obstruction was an important antecedent to the development of pigment gallstones (11). Thirdly, our case manifested uniquely as a plexiform or multinodular growth similar to a plexiform neurofibroma.

Histologically, schwannomas originating in the digestive tract show distinct histological features that distinguish them from conventional schwannomas. These schwannomas are S-100 protein-positive spindle cell tumors that are composed mainly of cellular (Antoni A) areas, and generally do not show a nuclear palisading pattern that is usually found in conventional schwannomas of the soft tissues (6, 12), Moreover, schwannomas of the digestive tract were recently reported to lack neurofibromatosis-2 genetic alterations, which support the theory that schwannomas of the digestive tract are unique tumors distinct from conventional schwannomas (13). In our case, the tumors showed a dominant Antoni A area, but had a nuclear palisading pattern. More cases are needed to determine the pathological correlation between a biliary schwannoma and other digestive schwannoma.

Schwannomas usually appear in CT as a homogenous mass with heterogeneous contrast enhancement and often show secondary degeneration such as a cystic change, cavity formation, necrosis, or calcification. However, secondary degeneration rarely occurs in schwannomas of the digestive tract (14). In our case, the tumors were too small to detect these radiology findings. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) might also be useful to establish the nature of the tumor. The MRI findings of schwannomas are mainly masses with low signal intensity on the T1-weighted images and inhomogeneous high signal intensity on the T2-weighted images (15).

Schwannomas of the digestone tract have an excellent prognosis after a surgical resection, similar to conventional schwannomas, and there is no evidence to date that these tumors have a malignant potential.

In conclusion, biliary schwannomas causing a biliary stricture are extremely rare and a preoperative diagnosis is quite difficult. However, these potentially curable tumors should be included in the differential diagnosis of tumors arising in the biliary system.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Computed tomographic scan shows mildly dilated intrahepatic bile duct and many small stones in the gallbladder.

Fig. 2

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiography shows a focal stricture of the proximal common bile duct and an upstream bile duct dilatation with stones. The cystic duct is inserted aberrantly into the right intrahepatic duct. Gallbladder stones are also observed.

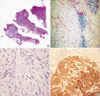

Fig. 3

(A) The specimen shows several well-demarcated nodules in the bile duct wall. (B) A nodule shows a typical pattern of a schwannoma consisting of spindle cells. Lymphocyte cuffing is also seen in the margin of the tumor (H&E ×100). (C) Magnified view shows interlacing fascicles with nuclear palisading (H&E ×200). (D) Immunochemical staining is positive for the S-100 protein (×100).

References

1. Malka D, Boige V, Dromain C, Debaere T, Pocard M, Ducreux M. Biliary tract neoplasm: update 2003. Curr Opin Oncol. 2004. 16:364–371.

2. Northover JM, Terblanche J. A new look at the arterial supply of the bile duct in man and its surgical implications. Br J Surg. 1979. 66:379–384.

3. Enzinger FM, Weiss SW. Soft tissue tumors. 1983. 1nd ed. St Louis, Mo: Mosby-Year Book;586–597.

4. Sarlomo-Rikala M, Miettinen M. Gastric schwannoma: a clinicopathological analysis of six cases. Histopathology. 1995. 27:355–360.

5. Miettinen M, Shekitka KM, Sobin LH. Schwannomas in the colon and rectum: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 20 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001. 25:846–855.

6. Honjo Y, Kobayashi Y, Nakamura T, Kakehira Y, Kitagqwa M, Ikematsu Y, Ozawa T, Nakamura H. Extrahepatic biliary schwannoma. Dig Dis Sci. 2003. 48:2221–2226.

7. Oden B. Neurinoma of the common bile duct: report of a case. Acta Chir Scand. 1955. 108:393–397.

8. Nagafuchi Y, Mitsuo H, Takeda S, Ohsato K, Tsuneyoshi M, Enjoji M. Benign schwannoma in the hepatoduodenal ligament: report of a case. Surg Today. 1993. 23:68–72.

9. Otani T, Shioiri T, Mishima H, Ishihara A, Maeshiro T, Matsuo A, Umekita N, Warabi M. Bile duct schwannoma developed in the remnant choledochal cyst-a case associated with total agenesis of the dorsal pancreas. Dig Liver Dis. 2005. 37:705–708.

10. Jakobs R, Albert J, Schilling D, Nuesse T, Riemann JF. Schwannoma of the common bile duct: a rare cause of obstructive jaundice. Endoscopy. 2003. 35:695–697.

11. Shiesh SC, Chen CY, Lin XZ, Liu ZA, Tsao HC. Melatonin prevents pigment gallstone formation induced by bile duct ligation in guinea pigs. Hepatology. 2000. 32:455–460.

12. Daimaru Y, Kido H, Hashimoto H, Enjoji M. Benign schwannoma of the gastrointestinal tract: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study. Hum Pathol. 1988. 19:257–264.

13. Lasota J, Wasag B, Dansonka-Mieszkowska A, Karcz D, Millward CL, Rys J, Stachura J, Sobin LH, Miettinen M. Evaluation of NF2 and NF1 tumor suppressor genes in distinctive gastrointestinal nerve sheath tumors traditionally diagnosed as benign schwannomas: study of 20 cases. Lab Invest. 2003. 83:1361–1371.

14. Levy AD, Quiles AM, Miettinen M, Sobin LH. Gastrointestinal schwannoma: CT features with clinicopathological correlation. Am J Roentgenol. 2005. 184:797–802.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download