Abstract

The KIDSCREEN-52 quality-of-life (KIDSCREEN-52-HRQOL) is a relevant, worldwide tool used for assessing the health-related quality of life in children and adolescents. The purpose of this study was to define measurement properties of the Korean version of the KIDSCREEN-52 HRQOL. The original questionnaire was translated following international translation guidelines. Analysis regarding psychometric properties showed that the Cronbach-alpha ranged from 0.77 to 0.95. The correlation coefficient between the PedQL and KIDSCREEN-52 dimensions were high for the assessments of similar constructs. Therefore, the Korean version of the KIDSCREEN-52 was found to be suitable for use in Korean adolescents.

Health-related quality of life (HRQOL) is generally conceptualized as a multidimensional construct encompassing domains including the psychological, mental, social, and spiritual areas of life (1-3). This conceptualization is in line with the World Health Organization definition of health as the state of complete physical, mental, and social wellbeing, and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity (1). In spite of various definitions of HRQOL in the current literature, an international consensus about the above-mentioned domains of HRQOL has evolved (3). For example, Ravens-Sieberer and Bullinger (4) have proposed the following definition, "HRQOL can be viewed as a psychological construct, which describes the physical, mental, social, psychological, and functional aspects of wellbeing and function from the patient perspective." Because HRQOL has become an important outcome measure in health care, valid, reliable, and simple instruments for measurement are needed. Until now, HRQOL research has focused mainly on adults, and thus only a limited number of instruments that measure the quality of children's and adolescents' health and wellbeing currently exist (5-7).

Only recently have health professionals focused on the importance of quality-of-life assessment in children and adolescents (8). Some dimensions of the adult HRQOL are not relevant for children (e.g. family, school, and peers). Changes in children's emotional and cognitive development must be recognized and addressed, and reading skills have to be considered (9). In general, children are often regarded as unreliable respondents (10-12). Therefore, early attempts to rate the HRQOL in children were based on data provided by mothers and other proxy reports. Recently, studies have shown that children, and adolescents are able to answer the HRQOL questionnaires reliably if their emotional development, cognitive capacity, and reading skills are taken into account (12).

KIDSCREEN-52 quality-of-life measure for children and adolescents (KIDSCREEN-52 HRQOL) was funded by the European Commission and developed as a self-report measure applicable to healthy and chronically ill children and adolescents eight to eighteen years of age. Various psychometric aspects of the KIDSCREEN-52-HRQOL had been studied by Ravens-Sieberer et al. in 12 European countries (9).

The aim of this study was to translate and validate the Korean version of the KIDSCREEN-52 quality-of- life measure (K-KIDSCREEN-52 HRQOL)

The K-KIDSCREEN-52 HRQOL was developed from the English KIDSCREEN-52, which was funded by the European KIDSCREEN group (9). It was translated into Korean according to international guidelines (13). The KIDSCREEN-52 generic HRQOL questionnaire was translated by a forward-backward-forward translation technique. In a first step two independently working psychiatrists translated the English Draft into the Korean language. Thus two different versions of translation were acquired (Forward Translation 1 and Forward Translation 2). In the following reconciliation step the two forward translators and one project member reviewed the respective two forward translations in order to create the respective Reconciled Forward Translation, meeting all demands of conceptual equivalence with the original English Draft. Afterwards the respective Reconciled Forward Translation was back translated into English by a third translator. In the next step two research members as well as the forward translator compared the respective Backward Translation with the Draft, thus reviewing the respective Reconciled Forward Translation and thereby generating the respective Final Forward Translation. Subsequent to the generation of the respective Final Forward Translation, all reviews and translation data was send to the German study center for documentation. The objective of the following telephone conference was to resolve inadequate concepts of translation as well as all discrepancies between alternative versions.

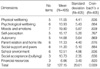

The KIDSCREEN-52 questionnaire consisted of 52 items assessing ten HRQOL dimensions (Table 1). It assessed either the frequency of behavior/feelings or intensity of an attitude. Both possible item formats use a 5-point Likert response scale, and the recall period is one week. Scores are computed for each dimension (i.e. items are equally weighted) and are transformed into T-values with a mean of 50 and a standard deviation of 10; higher scores indicate higher HRQOL and wellbeing (14).

All students from the seventh to ninth grade (age 13-15 yr) at one middle school in Seoul, Korea, were invited to take part in the study, provided that their understanding of the Korean language and their reading and writing skills were sufficient. The sample consisted of 405 adolescents, of which 204 were boys and 201 were girls. The mean age for the sample was 13.83 yr.

The students were told that the purpose of the study was to attain knowledge about the quality of life and health, in general, among teenagers. They were further informed that their responses would be treated anonymously and that there was no right or wrong answer. The scale instructions were given in written form, and the test was performed during school hours and lasted 30 to 40 min. The rights of all participants were safeguarded through informed consent and confidentiality.

To address the properties of the measure in terms of convergent and construct validity, several other measures were included, in addition to the K-KIDSCREEN-52 HRQOL. Convergent validity was assessed by comparison of K-KIDSCREEN-52 dimensions scores with the PedsQL™ 4.0, a known and validated questionnaire measuring similar concepts. The PedsQL™ 4.0 Generic Scales consists of an overall HRQoL scale, a 23-item Total Score, and eight-item Physical Health Summary subscale and a 15-item Psychosocial Health Summary subscale. The Psychosocial Health Summary subscale was further composed of a five-item Emotional Functioning subscale, a five-item Social Functioning subscale, and a five-item School Functioning subscale. The Physical Health Summary subscale was equivalent to and also referred to as the Physical Functioning subscale (15-17). We used the Korean version of the PedsQL™ 4.0. The internal consistency coefficient of the Korean version of the PedsQL™ 4.0 has been reported previously to be 0.93 (18). The Children's Depression Scale (CDI) (19, 20) and the Revised Children's Manifest Anxiety Scale (RCMAS) (21, 22), which have been widely used for self- report to measure depressive and anxiety symptoms, were included.

The statistical analyses for the reliability and validity of the K-KIDSCREEN were performed using SPSS for Windows (Version 10.0; SPSS, Chicago, IL, U.S.A.). The internal consistency of each subscale was estimated by using the Cronbach's alpha coefficient. Alpha coefficients of 0.7 or higher were considered acceptable. The test-retest reliability was estimated via a comparison of the scores achieved when add ministered on two separate occasions, at interval of one week. Pearson correlation coefficients were computed to analyze convergent validity between K-KIDSCREEN-52 dimensions and PedsQL™ 4.0, CDI, and RCMAS. Convergent validity was considered to be demonstrated when correlations between comparable dimensions were significantly higher than those between theoretically different dimensions and were of a reasonable magnitude. Correlation coefficients between 0.1 and 0.3 were considered low, those between 0.31 and 0.5 moderate, and those over 0.5 were considered high (9, 23).

The mean score of the K-KIDSCREEN 52 subscales, along with Cronbach's alpha coefficients, are presented in Table 2. Cronbach's alpha coefficients for the individual subscales were 0.77 or greater. The test-retest reliability of the K-KIDSCREEN was 0.759.

Table 3 shows the results of the convergent validity analysis. The K-KIDSCREEN-52 HRQOL and the PedsQL™ 4.0 dimensions showed a moderate level of correlation, but the expected relationships. The PedsQL™ 4.0 physical functioning correlated highest with the K-KIDSCREEN-52 HRQOL physical wellbeing dimension (r=0.32). The PedsQL™ 4.0 emotional functioning and relational functioning scale correlated highest with KIDSCREEN-52 moods and emotions (r=0.57, r=0.32). RCMAS and CDI were the most negatively correlated with the KIDSCREEN-52 moods and emotions dimension (r=-0.42, r=-0.34). However, the low correlation between the K-KIDSCREEN-52 HRQOL dimension school environment and the school functioning scale of the PedsQL™ 4.0 (r=0.14), and the K-KIDSCREEN-52 HRQOL dimension social support and peers and the relational functioning of the PedsQL™ 4.0 (r=0.22) requires further explanation.

Table 4 shows the inter-subscale correlations. In the K-KIDSCREEN 52 subscales, the highest correlation was observed between psychological wellbeing and social support and peers subscales, but the correlation was modest (r=0.59). The autonomy subscale was highly correlated with psychological wellbeing, social support and peers, and parent relation and home life subscales (r=0.45, 0.40, 0.50). The school environment subscale was highly correlated with the parent relation and home life, self-perception, and autonomy subscales (r=0.45, 0.41, 0.47).

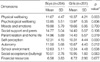

Table 5 shows mean T-values for the K-KIDSCREEN-52 dimensions stratified by gender. Differences by gender were found only in the physical wellbeing and self-perception dimensions.

According to the KIDSCREEN-52 HRQOL, scores are computed for each dimension and are transformed into T-values with a mean of 50 and a standard deviation of 10; higher scores indicate higher HRQOL and wellbeing (Appendix 1).

The K-KIDSCREEN-52 HRQOL questionnaire includes ten dimensions covering physical, psychologic, and social aspects of the HRQOL. The importance of perceived psychologic wellbeing was underscored by three dimensions; psychologic wellbeing, moods and emotions, and self-perception. In addition, a financial resources subscale was included. This dimension explored whether the adolescent felt that they have enough financial resources to allow them to live a lifestyle that was comparable with that of other adolescents and provided them with the opportunity to do things together with their peers.

Classic psychometric analysis confirmed the instrument's ability for sound measurement with sufficient psychometric properties. The instrument reliability was good, with a Cronbach' alpha coefficient of 0.76 or above for all dimensions.

We analyzed the validity of the physical, psychological, and social constructs of health by correlating the K-KIDSCREEN-52 with a similar instrument to assess HRQOL, the PedsQL™ 4.0. A comparison of K-KIDSCREEN-52 dimensions with PedsQL™ 4.0 scales showed the highest correlations for all similar concepts/dimensions (e.g., K-KIDSCREEN-52 HRQOL physical wellbeing dimension and physical functioning scale of the PedsQL™ 4.0). This refers to a satisfying convergent validity, which means that measures that should be related were in reality related. Theoretically expected low correlations (divergent validity) were, in fact, found for the K-KIDSCREEN-52 HRQOL financial resources dimension with all PedQL 4.0 scales. However, the low correlation between the K-KIDSCREEN-52 HRQOL dimension for school environment with the school functioning scale of the PedsQL™ 4.0, and the K-KIDSCREEN-52 HRQOL dimension for social support and peers and the relational functioning of the PedsQL™ 4.0 requires further explanation.

In general, girls were found to have a lower HRQOL in comparison with boys (24). In the present study, this was supported in only two dimensions: girls perception of their own body appearance was more negatively, and they were more concerned about their looks as well as their clothes (self-perception). In addition, they reported a lower physical wellbeing than boys. This result was consistent with a previous study (9).

Overall, the good reliability and validity determined for KIDSCREEN-52 HRQOL in the original study was also found in this study, therefore, the KIDSCREEN-52 HRQOL was cross-culturally validated in this study. Additional studies are needed to improve score interpretation for its use in clinical practice.

Using a HRQOL profile, based on dimension scores, can provide detailed information about impairments in certain HRQOL domains and can help suggest intervention strategies and, in the long run, prevention activities (9). Problematic HRQOL domains can be identified; whereas an overall score is difficult to interpret since different health patterns may result in similar overall scores (25, 26). Furthermore, different dimensions or scales of a HRQOL instrument display different degrees of sensitivity towards changes in HRQOL following therapeutic intervention. Thus, the use of a profile instrument is more valid for pre- and post-interventional measurements than a global valuation score (27).

There are several limitations of this study. First, the K-KIDSCREEN-52 HRQOL questionnaire was not tested in a clinical setting, therefore it needs to be tested in a clinical setting where clinical diagnoses and information about the severity of conditions are available. Further analyses will allow response patterns associated with those conditions to be identified and established (9). Second, the European KIDSCREEN-52 generic health-related quality of life questionnaire was developed for children and adolescents. Therefore, the K-KIDSCREEN-52 questionnaire needs to be tested in children, In several studies, a lower HRQOL was found in adolescents compared to children (28). Therefore, comparison between adolescents and children must be done. Third, exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis could be helpful to understand the factor structure of the KIDSCREEN-52 questionnaire.

In conclusion, a Korean translation of the KIDSCREEN-52 questionnaire was developed and verified for its reliability and validity. This instrument can be used as a reliable self-administered scale for assessing HRQOL in adolescents.

Figures and Tables

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

We gratefully thank Drs. Ulrike Ravens-Sieberer and Angela Gosch for helping us in developing the Korean version of the KIDSCREEN-52 HRQOL. We also acknowledge all the volunteers who participated in this study.

References

1. Eiser C, Morse R. A review of measures of quality of life for children with chronic illness. Arch Dis Child. 2001. 84:205–211.

2. Pal DK. Quality of life assessment in children: a review of conceptual and methodological issues in multidimensional health status measures. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1996. 50:391–396.

3. Spilker B. Quality of life assessments in clinical trials. 1990. New York, NY: Raven Press.

4. Ravens-Sieberer U, Bullinger M. Assessing health-related quality of life in chronically ill children with the German KINDL: first psychometric and content analytical results. Qual Life Res. 1998. 7:399–407.

5. Connolly MA, Johnson JA. Measuring quality of life in paediatric patients. Pharmacoeconomics. 1999. 16:605–625.

6. Eiser C, Morse R. The measurement of quality of life in children: past and future perspectives. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2001. 22:248–256.

7. Ravens-Sieberer U, Bullinger M. Manual KINDL-R. 2000. Hamburg, Germany:

8. Eiser C, Morse R. Quality-of-life measures in chronic diseases of childhood. Health Technol Assess. 2001. 5:1–157.

9. Ravens-Sieberer U, Gosch A, Rajmil L, Erhart M, Bruil J, Duer W, Auquier P, Power M, Abel T, Czemy L, Mazur J, Czimbalmos A, Tountas Y, Hagquist C, Kilroe J. European KIDSCREEN Group. KIDSCREEN-52 quality-of-life measure for children and adolescents. Expert Rev Phamacoeconomics Outcomes Res. 2005. 5:353–364.

10. Ravens-Sieberer U, Gosch A, Abel T, Auquier P, Bellach BM, Bruil J, Dur W, Power M, Rajmil L. Quality of life in children and adolescents: a European public health perspective. Soz Praventivmed. 2001. 46:294–302.

11. Eiser C, Morse R. A review of measures of quality of life for children with chronic illness. Arch Dis Child. 2001. 84:205–211.

12. Riley AW. Evidence that school-age children can self-report on their health. Ambul Pediatr. 2004. 4:371–376.

13. Guillemin F, Bombardier C, Beaton D. Cross-cultural adaptation of health-related quality of life measures: literature review and proposed guidelines. J Clin Epidemiol. 1993. 46:1417–1432.

14. Ravens-Sieberer U, Erhart M, Power M, Auquier P, Cloetta B, Hagquist C. Item-response-theory analyses of child and adolescent self-report quality of life data: the European corss-cultural research instrument KIDSCREEN. Qual Life Res. 2003. 12:722.

15. Varni JW, Seid M, Knight TS, Uzark K, Szer IS. The PedsQL 4.0 Generic Core Scales: sensitivity, responsiveness, and impact on clinical decision-making. J Behav Med. 2002. 25:175–193.

16. Varni JW, Burwinkle TM, Seid M, Skarr D. The PedsQL 4.0 as a pediatric population health measure: feasibility, reliability, and validity. Ambul Pediatr. 2003. 3:329–341.

17. Varni JW, Seid M, Kurtin PS. PedsQL 4.0: reliability and validity of the Pediatric Quality of Life inventory version 4.0 generic core scales in health and patient populations. Med Care. 2001. 39:800–812.

18. Choi ES. Psychometric test of the PedsQL 4.0 Generic Core Scale in Korean adolescents. 2004. Master Thesis in Yonsei University.

19. Kovacs M. Rating scales to assess depression in school-aged children. Acta Paedopsychiatr. 1981. 46:305–315.

20. Cho SC, Lee YS. Development of the Korean form of the Kovacs' children's depression inventory. J Korean Neuropsychiatr Assoc. 1990. 29:945–956.

21. Reynolds CR, Richmond BO. What I think and feel: A revised measure of children's manifest anxiety. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 1978. 6:271–280.

22. Choi JS, Cho SC. Assessment of anxiety in children: Reliability and validity of revised children's manifest anxiety scale. J Korean Neuropsychiatr Assoc. 1990. 29:691–702.

23. Borts J, Doring N. Forschungsmethoden und Evaluation. 1995. Berlin, Germany: Springer.

24. Bisegger C, Cloetta B, von Rueden U, Abel T, Ravens-Sieberer U. European Kidscreen Group. Health-related quality of life: gender differences in childhood and adolescence. Soz Praventivmed. 2005. 50:281–291.

25. Rogerson RJ. Environmental and health-related quality of life: conceptual and methodological similarities. Soc Sci Med. 1995. 41:1373–1382.

26. Riley AW, Green BF, Forrest CB, Starfield B, Kang M, Ensminger ME. A taxonomy of adolescent health: development of the adolescent health profile-types. Med Care. 1998. 36:1228–1236.

27. Allison PJ, Locker D, Feine JS. Quality of life: a dynamic construct. Soc Sci Med. 1997. 45:221–230.

28. Simeoni MC, Auquier P, Antoniotti S, Sapin C, San Marco JL. Validation of a French health-related quality of life instrument for adolescents: the VSP-A. Qual Life Res. 2000. 9:393–403.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download