Abstract

Here we report the first case of a Korean infant with a cloverleaf-shaped craniosynostosis, in which the diagnosis of Beare-Stevenson syndrome was suspected upon observation of the typical morphological features. This infant exhibited craniofacial anomalies, ocular proptosis, cutis gyrata, acanthosis nigricans, prominent umbilical stump, furrowed palms and soles, hypospadia, and sacral skin tag coupled with dermal sinus tract. Brain magnetic resonance imaging revealed that the patient also had non-communicating hydrocephalus with Chiari malformation. This is the 8th report of Beare-Stevenson syndrome in the literature, which was confirmed by the detection of a Tyr375Cys mutation in the fibroblast growth factor receptor 2 (FGFR2) gene.

Craniosynostosis refers to the premature closure of one or more cranial sutures, which results in an abnormal head shape. Craniosynostosis occurs in approximately 1:1,000-1:10,000 live births. Both isolated and syndromic forms of this condition have been differentiated, and have been implicated in more than 150 genetic disorders (1, 2). In isolated craniosynostosis, the infant exhibits no abnormalities other than craniosynostosis, which occurs secondarily to early sutural obliteration. Syndromic craniosynostoses tend to be hereditary and include a variety of other malformations of the extremities, backbone, and face. Different mutations have been associated with many cases of syndromic craniosynostosis, with overlapping phenotypes. In these patients, it is crucial to confirm the phenotypic diagnosis of syndromic craniosynostosis by molecular mutation analysis. Although the clarification of a genetic lesion has no direct impact, in many cases, on patient management, significant benefits are associated with accurate differential diagnoses.

Beare-Stevenson syndrome generally refers to a condition of syndromic craniosynostosis, which is characterized by a cloverleaf-shaped skull, craniofacial anomalies, ocular proptosis, cutis gyrata, acanthosis nigricans, prominent umbilical stump, furrowed palms and soles, and anogenital anomalies (3-5). In such cases, two specific mutations (Tyr375Cys and Ser372Cys) have been found in the fibroblast growth factor receptor 2 (FGFR2) gene, by Przylepa and colleagues (6).

Here, we report the case of Korean infant with Beare-Stevenson syndrome, which was verified by our detection of the Tyr375Cys mutation on the FGFR2 gene. The infant exhibited not only the clinical characteristics of Beare-Stevenson syndrome but was also found to exhibit non-communicating hydrocephalus and Chiari malformation.

The patient was a Korean male infant born at the 39th week of gestation via vaginal delivery at a regional maternity hospital. His mother was a 32-yr-old women and his father was a 50-yr-old man. His mother's obstetric history was gravida 2, para 1, and was otherwise unremarkable. Although the mother had undergone no antenatal care, her current pregnancy had been otherwise free of complications. In addition, neither side of the family had any history of consanguinity, structural anomalies, or genetic disorders.

The patient's Apgar scores were 6 and 8 at 1 and 5 min, respectively. Ten minutes after birth, the infant exhibited some signs of mild respiratory distress, including nasal flaring, grunting, stridor, and tachypnea. The patient was thus transferred to the Ansan Hospital, Korea University Medical Center.

Upon arrival at the neonatal intensive care unit, the patient exhibited coarse breathing sounds, and arterial oxygen saturation decreased gradually. The infant was therefore treated with continuous positive airway pressure, with extra oxygen being delivered via nasal prongs. A whole body radiograph revealed a cloverleaf-shaped skull deformity, and faint air bronchogram in both of the patient's central lungs.

The infant weighed 4,460 g (above 97th percentile), was 56 cm long (above 97th percentile), and had a head circumference of 36.5 cm (90-97th percentile). On physical examination, the combination of a frontal and bitemporal prominence, and a wide anterior fontanel (5×5 cm), gave the patient's skull an appearance reminiscent of a cloverleaf. The patient also suffered from hydrocephalus, resulting in a soft contour scalp without palpable suture lines. We noted severe ocular proptosis and ocular hypertelorism, and the patient exhibited exophthalmos, which was aggravated when the infant cried. The patient's mid-facial region was hypoplastic, with a small nose and a depressed nasal bridge. The infant's ears were angulated posteriorly, and were significantly lowset, with deep vertical furrows appearing in the pre-auricular area (Fig. 1). A skull anteroposterior view (Fig. 2) revealed severe temporal bulging, typical of a "cloverleaf" skull, as well as a 'scooping-out' effect apparent in the lacunar skull. The patient's maxillary bones were also found to be hypoplastic.

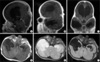

Next day, we performed brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (Fig. 3). The contrast-enhanced T1-weighted midsagittal scan revealed brachycephaly, the shallow posterior fossa, the herniated tonsil, the elongated 4th ventricle, and resultant dilatation of the lateral and third ventricles. The parasagittal scan clearly demonstrated the exophthalmos. Axial scans revealed a pen-lip schizencephaly in the patient's right middle cranial fossa.

On the 3rd day of birth, the infant manifested respiratory difficulty. Upon examination, the infant was feverish with purulent sputum, and exhibited inspiratory crackles with a mild intercostal retraction. At that time, the patient's chest radiography indicated mild bronchopneumonia. The patient was able to maintain normal oxygen saturations only when administered with oxygen with FiO2 40%, via intubation. We noted no abrupt symptomatic changes in the patient's condition, but observed a gradual and steady course of deterioration. The patient developed pneumonia, which was followed by the emergence of sepsis. At 21 days after birth, the patient went into cardio-respiratory arrest and expired. Mid-brain compression due to the craniosynostosis, which eventually resulted in central respiratory depression, was considered to be the underlying cause of death.

With the parents' consent, an autopsy was performed. A skin biopsy was obtained from the maculopapular linear pigmented region on the patient's left forearm, and the histopathological examination indicated acanthosis nigricans.

With given informed consent, in accordance with the standards provided by the local institutional review boards, DNA was extracted from the peripheral lymphocytes of the patient's blood, via the standard methods. We then conducted DNA analyses of the patient's FGFR2 gene (exon 10) using the polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-direct sequencing method. Using previously-described primer pairs (forward primer: 5'-TCAGTCTGGTGTGCTAACTCTATG-3'; reverse primer: 5'-TCCGCAGGGGATACGTTTG-3'), annealing temperatures, and PCR procedures (6). The PCR products were electrophoresed on 2% agarose gel (Promega, Madison, WI, U.S.A.) and stained with ethidium bromide. The DNA on the visualized bands was then extracted using a kit (Bio 101, Carlsbad, CA, U.S.A.), and sequenced in both directions with an automated DNA sequencer (ABI Prism 310 Genetic Analyzer, Perkin Elmer, Foster City, CA, U.S.A.).

PCR product sequencing revealed an amino acid substitution of cysteine, which is coded by TGC, for tyrosine, which is coded by TAC, at codon 375 (Tyr375Cys) of the FGFR2 gene (Fig. 4).

The cranial sutures and fontanelles normally close in a synchronized manner after birth, allowing the underlying brain and the rest of the skull to achieve their normal full size and shape. When this normal development is disrupted, debilitating pathological conditions can ensue. These conditions include craniosynostosis (premature cranial suture fusion) and cleidocranial dysplasia (delayed cranial suture closure). It has been reported that mutations in FGFR1, FGFR2, and FGFR3, as well as in the transcription factors MSX2 and TWIST, can induce craniosynostosis, and that mutations in the transcription factor RUNX2 (CBFA1) result in cleidocranial dysplasia.

The Tyr375Cys mutation in the FGFR2 gene, as was detected in our infant, is identical to the mutations previously detected in seven patients with Beare-Stevenson syndrome in the literature (5-10). Przylepa and colleagues (6) also detected a Ser372Cys mutation in a female infant who suffered from this syndrome.

Fibroblast growth factors are structurally-related proteins that are generally associated with cell growth, differentiation, migration, wound healing, angiogenesis, and oncogenesis. At the cellular level, the function of these growth factors appears to be mediated by transmembrane tyrosine kinase receptors, and fibroblast growth factor receptors. Four genes have been identified which encode fibroblast growth factor receptors, and mutations in three of these genes, namely FGFR1, FGFR2, and FGFR3, have been implicated in a variety of congenital, autosomal dominant disorders which affect craniofacial and skeletal development (11-13). Thus far, more than 60 mutations, a majority of which occur in FGFR2, have been associated with several clinically distinct forms of syndromic craniosynostosis. These include: Antley-Bixler-like syndrome, Apert syndrome, Beare-Stevenson syndrome, Crouzon syndrome, Crouzon and Acanthosis Nigricans syndrome, Jackson-Weiss syndrome, Muenke syndrome, and Pfeiffer syndrome. All of these mutations are dominant, and all of the syndromes listed above are characterized by craniofacial abnormalities with varying severities among conditions.

Despite the availability of molecular genetic analysis techniques, a complete physical examination and a careful review of medical and family histories constitute the first and most important steps in the evaluation of syndromic craniosynostoses. Clinical diagnosis should be used to determine which, if any, molecular testing should be subsequently conducted.

The changes in cranial and facial shape associated with these conditions appear to be strictly dependent on which suture(s) is (are) involved, the extent of bony fusion and its timing of onset, and the compensatory growth occurring in the remaining cranial regions not involved in the disease process. In the present case, the patient exhibited frontal and bitemporal prominences, coupled with a wide anterior fontanel. This resulted in the patient's skull taking on an appearance reminiscent of a cloverleaf.

In this case, the patient suffered from a typical craniosynostosis, but this was combined with non-communicating hydrocephalus, as well as a type II Chiari malformation. Cases of Beare-Stevenson syndrome coupled with Chiari malformations appear to be extremely rare. To the best of our knowledge, only four such cases have been previously reported (8, 14, 15), with the first having been described by Ito and colleagures (14).

Our patient's condition may be the end result of a premature closure of the cranial suture, which results in an increase in intracranial pressure, due to deficient cerebrospinal fluid flow and reduced venous uptake secondary to the small vascular channels and small foramen magnum. The cerebellum tonsil and brain stem are progressively displaced downward, resulting in the development of type II Chiari malformation. In our case, we also noted respiratory difficulty with recurrent pneumonia, as the result of laryngomalacia and aspiration of secretion. We inserted an endotracheal tube for ventilation support. However, after intubation, the patient experienced several attacks of apnea. These symptoms were probably attributable to central nervous lesions occurring as the result of the Chiari malformation and the increased intracranial pressure.

In this paper, we report the first case of a Korean infant with a cloverleaf-shaped craniosynostosis, in whom a suspected diagnosis of Beare-Stevenson syndrome was bolstered by the observation of the characteristic morphological features, and Chiari malformation. Furthermore, this is the 8th case report of Beare-Stevenson syndrome confirmed by the detection of a Tyr375Cys mutation on the FGFR2 gene in the literature.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Photographs of the patient. (A) Craniofacial anomalies with severe ocular proptosis and depressed nasal bridge. (B) Hypospadia of penis but two normal testicles. (C) Sacral skin tag with sinus tract. (D) Cutis gyrate in deeply furrowed right palm. (E) Cutis gyrate in deeply furrowed right sole. (F) Cutis gyrate in right preauricular furrows.

Fig. 2

Skull AP view showed typical "cloverleaf" skull with severe temporal bulging (white short arrows), lacunar skull (black arrow), poorly developed maxillary bone, and significantly low-set ears with angulated posteriorly (white long arrows).

Fig. 3

(A) The contrast-enhanced T1-weighted midsagittal image revealed brachycephaly and the findings consistent with Chiari malformation, including shallow posterior fossa, the herniated tonsil, caudally displaced medulla, elongated 4th ventricle, and resultant obstructive hydrocephalus. (B) The left parasagittal image depicted exophthalmos. (C) Contrast-enhanced T1-weighted coronal image showed schizencephaly in the right middle cranial fossa. T1-weighted (D), T2-weighted (E), and FLAIR (F) axial images also show schizencephaly in the right middle cranial fossa, and dilated lateral and third ventricles.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank the doctors and nurses at the neonatal intensive care unit, Department of Pediatrics, Ansan Hospital, Korea University Medical Center, for their enthusiastic support and cooperation.

References

1. Cohen MM Jr. Craniosynostoses: phenotypic/molecular correlations. Am J Med Genet. 1995. 56:334–339.

2. Katzen JT, McCarthy JG. Syndromes involving craniosynostosis and midface hypoplasia. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2000. 33:1257–1284.

3. Beare JM, Dodge JA, Nevin NC. Cutis gyratum, acanthosis nigricans and other congenital anomalies. A new syndrome. Br J Dermatol. 1969. 81:241–247.

4. Stevenson RE, Ferlauto GJ, Taylor HA. Cutis gyratum and acanthosis nigricans associated with other anomalies: a distinctive syndrome. J Pediatr. 1978. 92:950–952.

5. Hall BD, Cadle RG, Golabi M, Morris CA, Cohen MM Jr. Beare-Stevenson cutis gyrata syndrome. Am J Med Genet. 1992. 44:82–89.

6. Przylepa KA, Paznekas W, Zhang M, Golabi M, Bias W, Bamshad MJ, Carey JC, Hall BD, Stevenson R, Orlow S, Cohen MM Jr, Jabs EW. Fibroblast growth factor receptor 2 mutations in Beare-Stevenson cutis gyrata syndrome. Nat Genet. 1996. 13:492–494.

7. Krepelova A, Baxova A, Calda P, Plavka R, Kapras J. FGFR2 gene mutation (Tyr375Cys) in a new case of Beare-Stevenson syndrome. Am J Med Genet. 1998. 76:362–364.

8. Akai T, Iizuka H, Kishibe M, Kawakami S, Kobayashi A, Ozawa T. A case of Beare-Stevenson cutis gyrata syndrome confirmed by mutation analysis of the fibroblast growth factor receptor 2 gene. Pediatr Neurosurg. 2002. 37:97–99.

9. Wang TJ, Huang CB, Tsai FJ, Wu JY, Lai RB, Hsiao M. Mutation in the FGFR2 gene in a Taiwanese patient with Beare-Stevenson cutis gyrata syndrome. Clin Genet. 2002. 61:218–221.

10. Vargas RA, Maegawa GH, Taucher SC, Leite JC, Sanz P, Cifuentes J, Parra M, Munoz H, Maranduba CM, Passos-Bueno MR. Beare-Stevenson syndrome: Two South American patients with FGFR2 analysis. Am J Med Genet A. 2003. 121:41–46.

11. Zhang Y, Gorry MC, Post JC, Ehrlich GD. Genomic organization of the human fibroblast growth factor receptor 2 (FGFR2) gene and comparative analysis of the human FGFR gene family. Gene. 1999. 230:69–79.

12. Sarkar S, Petiot A, Copp A, Ferretti P, Thorogood P. FGF2 promotes skeletogenic differentiation of cranial neural crest cells. Development. 2001. 128:2143–2152.

13. Rice DP, Rice R, Thesleff I. Molecular mechanisms in calvarial bone and suture development, and their relation to craniosynostosis. Eur J Orthod. 2003. 25:139–148.

14. Ito S, Matsui K, Ohsaki E, Goto A, Takagi K, Koresawa M, Ito S, Sekido K, Suzuki M, Torikai K, Aida N. A cloverleaf skull syndrome probably of Beare-Stevenson type associated with Chiari malformation. Brain Dev. 1996. 18:307–311.

15. Wang TJ, Hung KS, Chen PK, Chuang WL, Shih TY, Lai BJ, Hsiao M. Beare-Stevenson cutis gyrata syndrome with Chiari malformation. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2002. 144:743–745.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download