Abstract

A rare case of bilateral third cranial nerve palsy due to a ruptured anterior communicating artery aneurysm is presented. A 68-yr-old woman was semicomatose with bilaterally fixed dilated pupil, abducted eyes, and ptosis. A computed tomography demonstrated extensive hemorrhage spreading around the both Sylvian and interhemisheric fissure without focal mass effect. Intracranial pressure via extraventricular drainage before surgery was 15-50 mmHg. Three months later, brain MRI showed infarction of left posterior cerebral artery territory and lacuna infarction of the pons. Eleven months after aneurysm repair, nerve palsy improved slowly and recovered partially. The patient communicated well with simple words. The author reviewed and discussed the possible mechanism of this rare neuro-ophthalmological manifestation in view of a false localizing sign.

The oculomotor nerve dysfunction is a well recognized manifestation of the internal carotid-posterior communicating artery (ICA-PComA) junction aneurysm and is considered to be a valuable localizing sign caused by direct pressure on the nerve. Remote intracranial aneurysms from the ocular motor system may also occasionally cause ocular motor disturbance, most commonly abducens nerve palsy, which has been known to be simply a false localizing sign due to general intracranial hypertension (1, 2).

The author reviewed and discussed the possible mechanism of this rare bilateral third cranial nerve palsy due to a ruptured anterior communicating artery (AComA) aneurysm in view of a false localizing sign.

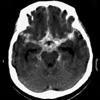

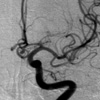

A 68-yr-old female was found unconscious. She was intubated and ventilated. Pulse rate and blood pressure were 68 beats per minute and 130/80 mm Hg, respectively. There was no history of diabetes mellitus, hypertension, heart disease, stroke, or cancer. On neurological examination, she was semicomatose with flexion to painful stimulation. Both pupils appeared centrally fixed, dilated (6 mm), and nonreactive to direct or indirect light stimuli. Computed tomographic (CT) scanning demonstrated extensive subarachnoid hemorrhage spreading around the both Sylvian, basal, and interhemispheric cistern (Fig. 1). Emergency extraventricular drainage (EVD) was performed. Initial intracranial pressure (ICP) was 45 mm Hg, and subsequently, the pressure remained between 15 and 25 mm Hg after intermittent cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) drainage. Seven hours after EVD, the right pupil became reactive to light, but left pupil was nonreactive to light with 4 mm in size. A digital subtraction angiogram revealed a saccular aneurysm on the AComA (Fig. 2). The patient underwent an operation on the next day via left pterional approach. After opening the Sylvian fissure, it was observed that the basal cistern was obstructed with clot. The aneurysm could be safely dissected and was successfully clipped. No additional neurological deficits were observed postoperatively. She was maintained with continuous EVD. On the 5th postoperative day, both pupils were dilated (6 mm) with sudden elevation of ICP to 50 mm Hg during temporary closure of ventricular catheter. Follow-up CT scan showed no significant change. Thereafter, the right pupil gradually decreased (2 mm) and reacted to light but the left one was still dilated without direct or indirect light reflex, in which pupil size changed a little in accordance with intermittent ventricular drainage. The ventricular catheter was removed on the 14th postoperative day when it was still measured at 25 mm Hg. Twenty days later, ventriculo-peritoneal shunting was done due to communicating hydrocephalus. Her left pupil decreased to 3 mm in size but did not react to direct or indirect light. There were still limitations of ocular movements of both eyes.

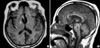

As her consciousness began to improve slowly after shunting over a period of weeks, it was noted that she was unable to open her both eyes, indicating bilateral ptosis. At this point, the author came to recognize these events and finally confirmed external ophthalmoplegia of the right eye and complete ophthalmoplegia of the left eye. Three months after surgery, follow-up magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) demonstrated infarction of left medial occipital lobe and lacunar infarction of the pons (Fig. 3). The final examination performed in one year showed that the patient communicated well with simple words, and that the left arm and leg remained at grade 4+ and the right side at grade 4. Also, both of her ophthalmoplegia recovered partially, resulting in intermittent spontaneous eye opening, lateral deviation in the right eye, centrally fixed pupil in the left eye, and both isocoric and reactive pupil (Fig. 4). However, she complained of diplopia and slightly decreased vision.

Bilateral third cranial nerve palsy as a false localizing sign due to a ruptured anterior communicating artery aneurysm is very rare because AComA aneurysms are not in the vicinity of the oculomotor nerve. Suzuki and Iwabuchi (3) recorded false localizing third cranial nerve palsy in two patients with ruptured aneurysms. These patients had A1 and AComA aneurysms and were presented with unilateral partial cranial nerve III palsy and bilateral total ophthalmoplegia, respectively. They explained in patient with A1 aneurysm and megadolichobasilar anomaly that the oculomotor nerve might be more easily displaced or squeezed between the posterior cerebral and superior cerebellar arteries by increased ICP. In another expired patient, a remarkable descent of the terminal portion of the basilar artery was found, indicating downward axial displacement of the midbrain by supratentorial hypertension, resulting in total ophthalmoplegia. A single case of an AComA aneurysm rupture in which bilateral oculomotor nerve palsy was presented was reported by Coyne and Wallace (4).

A number of mechanisms of a third nerve palsy in patients with an intracranial aneurysm have been classified by Fox (5). Direct peripheral causes include, 1) local pressure by the aneurysm, and 2) hemorrhagic dissection of the nerve. Direct central causes include bleeding into midbrain parenchyma or direct pressure of a large basilar artery on the nucleus. Indirect peripheral causes include increased ICP (from clot, edema, hydrocephalus) causing uncal herniation. Indirect central causes include increased ICP and vasospasm (6). The case of Coyne and Wallace (4) showed close similarity to the present case with respect to the pathogenesis but a little difference from clinical signs and course of the bilateral oculomotor nerve palsy. In their report, raised ICP without brain herniation and compression of the third nerves within the perimesencephalic cisterns by focal subarachnoid clot were suggested as possible underlying mechanisms of the palsies.

When the peripheral oculomotor nerve is involved by an aneurysm, usually the pupilloconstricter fibers are involved first, followed by palsy of the levator palpebrae, superior rectus, and medial rectus, in order. In contrast, when there is an intramedullary lesion, the pupilloconstricter fibers can be saved (7, 8). While the phenomenon of a pupil-sparing oculomotor nerve palsy caused by an aneurysm has been well documented, it is nonetheless an uncommon event (9-11). In diabetes, a pupil-sparing oculomotor nerve palsy leads to loss of myelin and axons within that central portion, but may spare the peripheral regions where pupillary fibers travel (12). In the present patient, it is likely that the microvascular supply to the inner nerve fibers of right third nerve was compromised while more peripheral fibers still received an adequate vascular supply.

It is clinically difficult to ascertain the exact pathophysiologic mechanism responsible for the present case. This nerve injury might be caused by 1) direct compression of the nerve derived from the extensive clot in the basal cistern, 2) uncal herniation, 3) remote effect due to increased ICP, and less likely, 4) vasospasm of branches of basilar artery. In the present patient, these several features typically seen in other reports were found to be co-existing. The development of infarction of left medial occipital lobe usually signifies incipient uncal herniation. Most likely, brain herniation, along with dense hemorrhage and increased ICP, is a mechanism of the left oculomotor nerve palsy. However, relatively good improvement of this patient's neurological deficits and the absence of midbrain and uncal lesion on MRI suggest that focal vasospasm is one rare possibility of infarction of this medial occipital lobe and lacunar infarction of the pons. In contrast, the remote effect due to increased ICP could conceivably account for pupillary change of the right eye according to ventricular drainage.

Eye opening on command or painful stimulus is most significant within the first 72 hr following an injury. After this time, even patients who will remain vegetative may open their eyes spontaneously. Delay in the diagnosis of this condition after surgery could be common because of lack of recognition of ptosis in an unconscious patient.

Despite considerable variety in the degree of recovery, many patients show little functional impairment. However, this relates to the nature of the hemorrhagic insult. It seems to be possible that early operative decompression of the cistern and direct neck clipping are the therapeutic maneuvers most likely to produce ultimate ocular recovery in the present case.

In conclusion, the incidence of bilateral third cranial nerve palsy due to a ruptured AComA aneurysm as a false localizing sign is very rare. It will be difficult to evaluate the result if the neuro-ophthalmological examination was limited by the poor clinical grade of the patients with ruptured intracranial aneurysms. Therefore, more meticulous neuro-ophthalmological examination should be done to evaluate cranial nerve palsy.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 1Computed tomographic scanning demonstrates extensive hemorrhage spreading around the both Sylvian, basal, and interhemispheric cistern. |

| Fig. 2A digital subtraction angiogram reveals a saccular aneurysm on the anterior communicating artery. |

References

1. Lee CH, Koh YC. Ruptured posterior communicating artery aneurysm causing bilateral abducens nerve paralyses. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2000. 29:426–429.

2. Ziyal IM, Ozcan OE, Deniz E, Bozkurt G, Ismailoglu O. Early improvement of bilateral abducens nerve palsies following surgery of an anterior communicating artery aneurysm. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2003. 145:159–161.

3. Suzuki J, Iwabuchi T. Ocular motor disturbances occurring as false localizing signs in ruptured intracranial aneurysms. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1974. 30:119–128.

4. Coyne TJ, Wallace MC. Bilateral third cranial nerve palsies in association with a ruptured anterior communicating artery aneurysm. Surg Neurol. 1994. 42:52–56.

5. Fox JL. Intracranial aneurysms. 1983. New York: Springer;163–183.

6. Kudo T. Postoperative oculomotor palsy due to vasospasm in a patient with a ruptured internal carotid artery aneurysm: a case report. Neurosurgery. 1986. 19:274–277.

8. Trobe JD. Third nerve palsy and the pupil. Footnotes to the rule. Arch Ophthalmol. 1988. 106:601–602.

9. Good EF. Ptosis as the sole manifestation of compression of the oculomotor nerve by an aneurysm of the posterior communicating artery. J Clin Neuroophthalmol. 1990. 10:59–61.

10. Kissel JT, Burde RM, Klingele TG, Zeiger HE. Pupil-sparing oculomotor palsies with internal carotid-posterior communicating artery aneurysms. Ann Neurol. 1983. 13:149–154.

11. Terry JE, Stout T. A pupil-sparing oculomotor palsy from a contralateral giant intracavernous aneurysm. J Am Optom Assoc. 1990. 61:640–645.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download