Abstract

We report a case of 61-yr-old man with stable psoriasis who progressively developed generalized pustular eruption, erythroderma, fever, and hepatic dysfunction following oral terbinafine. Skin biopsy was compatible with pustular psoriasis. After discontinuation of terbinafine and initiating topical corticosteroid and calcipotriol combination with narrow band ultraviolet B therapy, patient'S condition slowly improved until complete remission was reached 2 weeks later. The diagnosis of generalized pustular psoriasis (GPP) induced by oral terbinafine was made. To our knowledge, this is the first report of GPP accompanied by hepatic dysfunction associated with oral terbinafine therapy.

Terbinafine is a member of allylamine class of antifungal agents, which have been used effectively to treat dermatomycoses (1). Although it generally has been well tolerated, several cases of generalized pustular psoriasis (GPP) after oral terbinafine therapy have been reported. However, in no report has hepatic dysfunction been associated with a GPP after terbinafine therapy. Herein, we report a case of terbinafine induced GPP with an elevation in his liver function tests, and to the best of our knowledge, this is the first in literature.

A 61-yr-old man with 5-yr history of stable psoriasis was admitted to our hospital for generalized erythroderma and micropustular eruption. He had been treated elsewhere for clinically diagnosed onychomycosis with terbinafine 250 mg daily and had discontinued therapy after 4 days of treatment due to such events. Patient did not recognize of any other drug history within 2 months, nor had any history of liver disease. There was no family history of psoriasis and the patient was not on medication for psoriasis since it had remained stable in recent 1 yr.

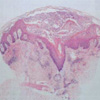

On admission, the patient revealed widespread erythema and multiple tiny pustules were studded on neck, trunk and both extremities (Fig. 1). The patient had a fever of 39.1℃ and complained of constitutional symptoms of general weakness, arthralgia and myalgia. The white cell count was 24.09×109/L with marked neutrophilia. Baseline liver function studies performed prior to administration of terbinafine were within normal range. Cultures for bacteria and fungi from the pustules did not reveal any organism. Skin biopsy revealed psoriasiform acanthosis and subcorneal spongiform pustules filled with neutrophils (Fig. 2). There was sparse exocytosis of eosinophils, and superficial dermal edema was not prominent. Neither necrotic keratinocytes nor signs of vasculitis were present. The histopathological findings were consistent with clinical diagnosis of pustular psoriasis rather than acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP). Liver function studies after 4 days of admission revealed SGOT 219 IU/L (normal range <40 IU/L), SGPT 376 IU/L (<44 IU/L), and alkaline phosphatase 564 IU/L (95-280 IU/L), while blood serology excluded viral hepatitis. Therapy during the admission consisted of topical corticosteroid and calcipotriol combination with narrow band ultraviolet B. After 2 weeks of treatment, there was near complete resolution of the skin eruption and elevated liver enzymes returned to normal. He remains well and free of any pustular eruptions 18 months later and liver function marker has been preserved in normal range during the follow up.

Adverse effects have been reported in 10.5% of patients receiving oral terbinafine (1). Common cutaneous adverse reactions are rash, pruritus, urticaria, and eczema (1). Less common but more significant or life-threatening cutaneous reactions include acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis, erythema multiforme, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, toxic epidermal necrolysis, exacerbation or induction of psoriasis and erythroderma (2-9). Hepatobiliary toxicity has been reported much infrequently in 0.2% (1).

Pustular eruptions associated with terbinafine have rarely been reported in literature. To our knowledge, there are 11 cases of AGEP and 4 cases of GPP induced by terbinafine (Table 1). Among those reports of GPP, only 1 case was exacerbating from pre-existing psoriasis and we could not find any documented case accompanying with significant hepatic involvements.

GPP and AGEP are uncommon condition characterized by generalized sterile micropustular eruption. However, GPP clinically and histologically may be difficult to distinguish from AGEP. Moreover, if GPP has a history of preceding drug exposure, the differentiation may be much more challenging (10). Although there have been no clear-cut rules, some studies described peculiar characteristics that may justify the distinction. Roujeau et al. (11) described that AGEP usually shows massive edema in the superficial dermis, vasculitis, exocytosis of eosinophils, and single-cell necrosis of keratinocytes, while pustular psoriasis shows papilloacanthosis. Spencer et al. (10) cited that the absence of a personal or family history of psoriasis, rapid resoluton after withdrawal of the offending agents, the presence of a variable numbers of eosinophil infiltrations, and absence of psoriasiform histologic features; all suggest of pustular drug eruptions (AGEP). In present case, patient's past history of stable psoriasis and typical histological feature of psoriasis strongly suggest of pustular psoriasis rather than AGEP. Histologically not containing eosinophils in his biopsy specimen also favored the diagnosis. Because of widespread desquamative and pustular erythroderma associated with fever and altered general conditions, this case is considered pustular psoriasis of the von Zumbusch type.

In conclusion, our case suggests that oral terbinafine can provoke GPP concomitantly with hepatic involvement, and therefore physicians should carefully monitor hepatic enzymes when serious cutaneous adverse events occur during the use of terbinafine.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

(A) Generalized erythema covered with tiny pustules and scalings. (B) Close-up view of pustules on erythematous background.

References

1. Hall M, Monka C, Krupp P, O'Sullivan D. Safety of oral terbinafine: results of a postmarketing surveillance study in 25,884 patients. Arch Dermatol. 1997. 133:1213–1219.

2. Kempinaire A, De Raeve L, Merckx M, De Coninck A, Bauwens M, Roseeuw D. Terbinafine-induced acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis confirmed by a positive patch-test result. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997. 37:653–655.

3. Ham SH, Ha SJ, Park YM, Cho SH, Kim JW. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis induced by terbinafine. J Asthma Allergy Clin Immunol. 1998. 18:330–334.

4. Hall AP, Tate B. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis associated with oral terbinafine. Australas J Dermatol. 2000. 41:42–45.

5. Carstens J, Wendelboe P, Sogaard H, Thestrup-Pedersen K. Toxic epidermal necrolysis and erythema multiforme following therapy with terbinafine. Acta Derm Venereol. 1994. 74:391–392.

6. Gupta AK, Lynde CW, Lauzon GJ, Mehlmauer MA, Braddock SW, Miller CA, Del Rosso JQ, Shear NH. Cutaneous adverse effects associated with terbinafine therapy: 10 case reports and a review of the literature. Br J Dermatol. 1998. 138:529–532.

7. Rzany B, Mockenhaupt M, Gehring W, Schopf E. Stevens-Johnson syndrome after terbinafine therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994. 30:509.

8. Gupta AK, Sibbald RG, Knowles SR, Lynde CW, Shear NH. Terbinafine therapy may be associated with the development of psoriasis de novo or its exacerbation: four case reports and a review of drug-induced psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997. 36:858–862.

9. Wilson NJ, Evans S. Severe pustular psoriasis provoked by oral terbinafine. Br J Dermatol. 1998. 139:168.

10. Spencer JM, Silvers DN, Grossman ME. Pustular eruption after drug exposure: is it pustular psoriasis or a pustular drug eruption? Br J Dermatol. 1994. 13:514–519.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download