Abstract

Primary cardiac sarcoma is a rare disease in adults. It is also associated with poor prognoses, due to diagnostic delay, therapeutic difficulty, and high metastatic potential. The coincidence of pregnancy and a primary cardiac intimal sarcoma is extremely rare. We report a pregnant woman at 27+5 weeks gestation who was admitted to the hospital with acute-onset dyspnea. A mass was found on the left atrium by transthoracic echocardiography. Subsequently, the intracardiac mass was removed, and mitral valve replacement and modified DeVega tricuspid annuloplasty were performed. The patient was diagnosed with a undifferentiated sarcoma, and gave birth to a 1,230 g living baby boy by Caesarean section from preterm contraction at 29+5 weeks gestation. The patient then received systemic chemotherapy. However, 10 months after the initial clinical onset, the patient suddenly died. Surgery is the standard treatment for cardiac tumors, and their removal should always be attempted, even in pregnant women. Although the overall survival rates of the patients are rather poor, palliative cardiac surgery allows the prolonging of pregnancy, until an acceptable fetal viability level is reached.

Unlike metastatic cardiac involvement by disseminated neoplasms, primary tumors of the heart are rare. In a review of 22 autopsy series, the incidence of such tumors stands at about 0.02%, with only one-quarter of these cases exhibiting malignant histopathological features (1). Moreover, the coincidence of pregnancy with one of these primary heart tumors is an extremely rare occurrence. Only four other cases of primary cardiac sarcoma (PCS) in pregnancy have been reported previously in the literature (2-5).

Here, we report a patient presenting at 27+5 weeks gestation with dyspnea, and diagnosed with a primary cardiac sarcoma.

A 29 yr old woman at 27+5 weeks gestation (gravida 1, para 0) was hospitalized due to dyspnea (NYHA IV) which had started 10 days before. The patient was healthy in the past, and the prenatal care findings of the local clinic were nonspecific. According to physical examination, dyspnea was aggravated at the inspiratory phase and right decubital position. Blood pressure was 120/80 mmHg, and her pulse rate evidenced tarchycardia of 120 beats/min. Both of her neck veins were engorged.

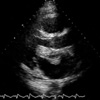

Routine blood tests and chest radiography were performed, but resulted in no peculiarity. Transthoracic echocardiography revealed a 5 cm in diameter echogenic mass spreading from the anterior of the left atrium to the mitral leaflet and mitral annulus, severe eccentric mitral regurgitation coupled with severe stenosis, and severe pulmonary hypertension (Fig. 1). The fetus was at a size consistent with IUP 27+2 weeks, according to obstetric sonography, and appeared to be normal. The patient was given intramuscular dexamethasone, 5 mg every 12 hr for 4 doses.

The operation on the intracardiac mass was carried out via median sternotomy. Continuous fetal heart rate and uterine monitoring were performed using cardiotocography throughout the procedure. On the area connecting the sternal body and the xiphoid process, we found a tumor mass about 2 cm in diameter. A diagnosis by frozen section identified the mass as sarcoma. We began normothermic cardiopulmonary bypass. The mass originating from the atrioventricular wall was found to have spread all the way to the leaflet and annulus of the anterior of the mitral valve, so we were compelled to settle for an incomplete resection of the mass (Fig. 2). We also performed a mitral valve replacement and a modified DeVega tricuspid annuloplasty. There was no evidence of fetal compromise during the operation according to cardiotocographic monitoring.

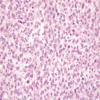

Permanent histopathological examination revealed a undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma (Fig. 3). The tumor was immunoreactive for vimentin, but immunohistochemical stains for cytokeratin, myoglobin, desmin, SMA, S-100 and CD34 were negative.

After operation, the patient exhibited stable vital signs and the cardiotocographic monitoring presented nonspecific findings. However, she developed preterm contraction at 29+5 weeks gestation, and we had to deliver a 1,230 g baby by Caesarean section, whose condition was stable, with Apgar scores of 5 at 1 min and 7 at 5 min. The operative findings of both ovaries were nonspecific, and postoperative staging with whole body computerized tomography was negative. We, therefore, concluded that the cardiac mass had indeed been primary sarcoma.

The patient then received systemic chemotherapy, with adriamycin, ifosfamide and darcarbazine. Although the patient exhibited neutropenia during 3 of the 8 courses of chemotherapy, she recovered without any particular complications. two months after chemotherapy, the patient was again hospitalized for dyspnea and severe abdominal distension. The results of examinations showed that global function was normal and the mitral prosthetic valve functioned well on echocardiography. However, computed tomography found a huge solid mass in the patient's right pelvic cavity (Fig. 4). After laparotomy, additional masses were observed. Therefore, we performed a right oophorectomy for the 30 cm in diameter right ovarian mass, and an omentectomy for the 20 cm in diameter omental mass, both of which were diagnosed as metastatic sarcoma (Fig. 5). ten months after the initial clinical onset, the patient died suddenly. Autopsy was not performed. The infant is presently alive and healthy.

Primary cardiac tumors are rarely curable by surgery. Complete resection of the tumors is difficult, due to the proximity to vital structures, and moreover, these tumors are likely to recur. However, it has been established that surgery, as a treatment, still has value, in that surgical removal of these tumors improves hemodynamic cardiac function, thereby improving the outcome of the patient and, especially when the tumor can be completely excised, surgery facilitates prolonged survival (6). Furthermore, the surgical removal of cardiac tumors has greater significance when it comes to pregnant women. Palliative cardiac surgery allows the prolonging of pregnancy until suitable fetal viability is reached (2).

As for adjuvant treatment, the role of adjuvant treatment in the case of resected PCS remains somewhat controversial, but it should be a reasonable conclusion that chemotherapy should be the choice for adjuvant therapy, as local relapse in PCS is relatively rare, and the common cause of death is not local relapse but metastatic recurrence.

Recent improvements in neonatal care have improved survival of premature infants greater than 28 weeks gestation. Generally, complete resection is performed as PCS is diagnosed, and if there is no evidence of metastasis, the patient may be closely observed until 28 weeks of gestation. In this case, complete resection was not performed during the operation and hence, adjuvant therapy (chemotherapy or radiotherapy) was considered as gestation corresponded to 28 weeks. However, Cesarean section was performed due to preterm contraction during post-operative care.

Open-heart operations have been performed at any gestational age, but are best performed between 24 and 28 weeks gestation, after the completion of organogenesis, or in the third trimester if a modern neonatal intensive care unit is available (7).

Cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) was first used during pregnancy in 1958. After initial trials, maternal mortality for pregnant patients undergoing CPB became as low as 2.9%. Interestingly, this figure is fairly close to the mortality figures for non-pregnant patients, although the fetal loss rate in pregnant patients undergoing CPB is still reported to be as high as 20% (8). The standard CPB approach (i.e., hemo-diluted, non-pulsatile flow, hypotension, hypothermia) might, however, prove detrimental in terms of uteroplacental perfusion and fetal development. The dilution effect of CPB is thought to reduce hormonal levels (progesterone in particular), which might augment uterine excitability. Also, experimental evidence suggests that CPB induces a prostaglandin-mediated increase in placental vascular resistance, which might effect a reduction in placental blood flow. While a non-pulsatile flow might be detrimental, pulsatile pressure has its own merit, as it is believed to attenuate uterine contractions via the release of endothelium-derived growth factor from the vascular endothelium (9). Uterine contractions occurring in the background of decreased perfusion and relative hypotension associated with CPB may provide inadequate placental perfusion, causing bradycardia in the fetus as a response. Hypothermia can also induce alterations in acid-base status; lead to coagulation disorders, arrhythmia, and ventricular fibrillation; and precipitate uterine contractions, thus reducing placental oxygen exchange. Embryofetal mortality was 24.0% when hypothermia was used, compared with 0.0% while operating under normothermal conditions (8).

In summary, we present a very unusual coincidence of pregnancy and a PCS, in which prompt resection allowed successfully the subsequent delivery of a living infant.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 1Transthoracic echocardiography shows a mass spreading from the anterior of the left atrium to the mitral leaflet and mitral annulus. |

| Fig. 2The mass originating from the atrioventricular wall was found to have spread all the way to the anterior leaflet and annulus of the mitral valve. |

| Fig. 3Photomicrograph of the undifferentiated cardiac intimal sarcoma. (A) The tumor is a highly cellular, showing areas of coagulative necrosis without any organoid pattern (H&E, ×40). (B) The high power view shows tumor cells with oval to spindle shaped, hyperchromatic or vesicular nuclei and frequent mitoses (H&E, ×400). |

References

2. Ceresoli G, Passoni P, Benussi S, Alfieri O, Dell'Antonio G, Bolognesi A. Primary cardiac sarcoma in pregnancy: a case report and review of the literature. Am J Clin Oncol. 1999. 22:460–465.

3. Simon BC, Funck R, Drude L, Bohle RM, Reichart B, Maisch B. Malignant angiosarcoma of the right atrium in pregnancy. Herz. 1994. 19:166–170.

4. Salamat SM, Landy HJ, O'Sullivan MJ. Pulmonary artery sarcoma in a pregnant woman: report of a case. Obstet Gynecol. 1994. 84:668–669.

5. Laya MB, Mailliard JA, Bewtra C, Levin HS. Malignant fibrous histiocytoma of the heart. A case report and a review of the literature. Cancer. 1987. 59:1026–1031.

6. Putnam JB Jr, Sweeney MS, Colon R, Lanza LA, Frazier OH, Cooley DA. Primary cardiac sarcomas. Ann Thorac Surg. 1991. 51:906–910.

7. Parry AJ, Westaby S. Cardiopulmonary bypass during pregnancy. Ann Thorac Surg. 1996. 61:1865–1869.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download