Abstract

There have been reports in Korea of imported malaria cases of four Plasmodium species, but there has been no report of imported Plasmodium ovale malaria confirmed by molecular biological methods. We report an imported case of that was confirmed by Wright-Giemsa-stained peripheral blood smear and nested polymerase chain reaction targeting the small subunit ribosomal RNA gene. The amplified DNA was sequenced and compared with other registered P. ovale isolates. The isolate in this study was a member of the classic type group. The patient was a 44-yr-old male who had worked as a woodcutter in Côte d'Ivoire in tropical West Africa. He was treated with hydroxychloroquine and primaquine and discharged following improvement. In conclusion, P. ovale should be considered as an etiology in the imported malaria in Korea, because the number of travelers to P. ovale endemic regions has recently increased.

Plasmodium ovale is a cause of benign and relapsing tertian malaria and the least common among the human-infecting Plasmodium species (1). Plasmodium ovale infections have been found in tropical Africa, the Middle East, Papua New Guinea, and Southeast Asia (2, 3). It has been thought that P. ovale is relatively common in tropical Africa and New Guinea with a prevalence of 10% to 15% among Plasmodium-infected patients (4, 5). Recently, P. ovale infections have been reported in Southeast Asia (2, 3). The prevalence of P. ovale infections in Southeast Asia (southern Vietnam, Thai-Myanmar border, Laos, and Indonesia) has been quoted as ranging from 2.0% to 9.4% (3).

In Korea, there have been some reports about imported cases of four human-infecting Plasmodium species in Korea (7-9), but there has been no report of imported P. ovale confirmed by molecular biological methods. We report a case of imported P. ovale infection confirmed by nested polymerase chain reaction (PCR) targeting the small subunit ribosomal RNA (SSU rRNA) gene. The gene was sequenced and compared with other registered P. ovale isolates.

A 44-yr-old male was admitted to hospital with fever of three days duration in October 2004. He had worked as a woodcutter in Côte d'Ivoire in tropical West Africa from May 1995 to January 2004. He had suffered from malaria in October 2002 and was treated with antimalarial drugs, but he did not remember the type of malaria or treatment regimen applied. He returned to Korea in January 2004 and has never since traveled abroad. His body temperature at presentation was 40.4℃. Physical examination findings were unremarkable. A routine complete blood count with differential counts revealed anemia (hemoglobin, 12.3 g/dL) and thrombocytopenia (44,000/µL). Lactate dehydrogenase (660 IU/L), alanine aminotransferase (63 IU/L), and γ-glutamyl transpeptidase (124 IU/L) were increased. Other hematological and biochemical profiles were within normal limits. Plasmodium lactate dehydrogenase (OptiMal Rapid Malaria Test, DiaMed, Morat, Switzerland) was negative. However, Wright-Giemsa-stained peripheral blood smear showed various stages (ring forms, schizonts, and gametocytes) of a Plasmodium species. Plasmodium-infected RBCs were enlarged and showed fimbriated margins (Fig. 1). Parasite density was 3,000 parasites/µL. The patient was treated with hydroxychloroquine for 3 days and was discharged with clinical improvement and prescribed primaquine for 14 days to prevent relapse. A subsequent visit to the outpatient clinic after one month showed normal hematological and biochemical profiles. No Plasmodium species was detected on the follow-up peripheral blood smear.

To differentiate the species of Plasmodium and evaluate mixed species infection, a nested PCR targeting the SSU rRNA gene was performed and P. ovale single infection was confirmed.

DNA was isolated from blood samples of the patient using QIAamp DNA Blood Mini kit (QIAGEN GmbH, Hilden, Germany). A nested PCR targeting the SSU rRNA gene was performed according to the protocols described by Snounou et al. (9). A set of genus specific primers (rPLU5/rPLU6) was used for the first round of amplification and four sets of species-specific primers (rFAL1/rFAL3 for P. falciparum, rVIV1/rVIV2 for P. vivax, rMAL1/rMAL2 for P. malariae, and rOVA1/rOVA2 for P. ovale) were used for the second round. Amplification was performed in a 20 µL reaction mixture containing the following: 0.2 µM of each primer; 200 µM (each) dATP, dCTP, dTTP, and dGTP; 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 9.0), 1.5 mM MgCl2, 40 mM KCl; 1 unit of Taq polymerase (Perkin-Elmer, Cetus, CT, U.S.A.); and 1 µL of DNA sample (or 1 µL of first-round PCR product for the second-round amplification). First- and second-round PCRs were performed using the same amplification condition. Forty cycles of amplification were preformed in a DNA thermal cycler (iCycler Thermal Cycler, Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, U.S.A.). Each cycle consisted of the followings: predenaturation at 95℃ for 5 min, 5 amplification cycles of (denaturation at 95℃ for 1 min, primer annealing at 58℃ for 2 min, and extension at 72℃ for 2 min), 35 amplification cycles of (denaturation at 95℃ for 1 min, primer annealing at 55℃ for 2 min, and extension at 72℃ for 2 min), and 72℃ for 10 min. The sizes of the amplified DNA fragments were -1,000 bp, 205 bp, 144 bp, 120 bp, and 788 bp for genus Plasmodium, P. falciparum, P. vivax, P. malariae, and P. ovale, respectively. Only P. ovale DNA was detected in the patient's peripheral blood (Fig. 2).

The PCR product was sequenced at Solgent (Daejeon, Korea). For the SSU rRNA gene, rPLU5 and RPLU6 were used. It was sequenced in both directions using the BigDye Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, U.S.A.). Sequencing products were resolved with an ABI 3730 XL autoanalyzer (Applied Biosystems). To compare gene sequences for the SSU rRNA genes, Nigerian I/CDC strain (L48997), NAG/Cameroon (AJ00157), MAL/MAI (X99790), and Papua New Guinea (AF145337) were used. We chose P. falciparum (AF145334), P. vivax (AF145335), and P. malariae (AF145336) as an outgroup. Nucleotide sequences were aligned using BioEdit (North Carolina State University, Raleigh, NC, U.S.A.). The aligned sequences were analyzed by the maximum likelihood method using fastDNAmL and distance methods using the neighboring distance method included in PHYLIP (Version 3.63, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, U.S.A.). The alignment of the P. ovale partial sequence of the SSU rRNA gene showed that our isolate (SM04-119, DQ104413) was more similar to isolates of Nigerian I/CDC and Papua New Guinea (identity 98.3% and 97.9%, respectively) than to those of NGA/Cameroon and MAL/MAI (95.8% and 95.4% identity, respectively) (Fig. 3).

Accurate diagnosis of the Plasmodium species is essential for adequate treatment of malaria. To identify Plasmodium species, microscopic examination of Giemsa-stained blood smears has been the diagnostic method of choice (10). However, it is not easy to identify P. ovale on a blood smear, particularly when parasite numbers are low and mixed species infections are present (11). In P. ovale endemic areas, the frequency of single P. ovale infection is very low, while the frequency of mixed species infection involving P. ovale was very high (2, 3, 9, 12). In these areas, P. ovale was more frequently observed using PCR methods (3.8-16.5%) than with conventional blood smear methods (0-0.4%) (2, 3, 9, 12). Therefore, it is reasonable to use nucleic acid detection methods simultaneously with the conventional blood smear methods for the purpose of identifying the species of imported malaria. Nevertheless, in this case, there was no difficulty in identifying P. ovale on the blood smear, because the typical morphology of P. ovale (various stages of Plasmodium in enlarged RBCs with fimbriated margins) was observed.

Côte d'Ivoire is a country in tropical West Africa. The prevalence of malaria parasitemia in West Africa is three times higher than that in East Africa (14). In Côte d'Ivoire, it has been reported that the prevalence of malaria parasitemia was 60% in children under 14 yr and the proportion of the population with P. ovale infection was 2% (14).

In contrast to P. falciparum and P. vivax, little is known about the patterns of genetic diversity in isolates of P. ovale (1). So far, full sequence of the SSU rRNA genes has been analyzed for eight isolates: two Nigerian I/CDC strains (13), CAG/Cameroon (AJ001527), MAL/MAI (X99790), a classic type Southeast Asian isolate (1), and three variant type Southeast Asian isolates (1). Nigerian I/CDC and Papua New Guinea isolates are members of the classic type group and CAG/Cameroon and MAL/MAI isolates are members of the variant type group (1). Partial sequences of the Papua New Guinea isolates could be compared with the isolate in this study because they were analyzed using the rPLU5 and rPLU6 primers. They are members of the classic type group (Fig. 3). There have been several reports about P. ovale in Côte d'Ivoire (14, 15), but no registered P. ovale isolate from Côte d'Ivoire is available. The isolate in this study (SM04-119, DQ104413) belonged to the classic type group (Fig. 3).

In summary, P. ovale should be considered as an etiology for imported malaria in Korea because the number of travelers and expatriates to P. ovale endemic regions has recently increased.

Figures and Tables

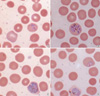

Fig. 1

Wright-Giemsa-stained peripheral blood smear (magnification, ×1,000). (A) a ring form in an enlarged red blood cell with fimbriated margin, (B) a schizont with eight merozoites distributed like a daisy-head, (C) a microgametocyte with eccentric and dispersed chromatin, (D) a macrogametocyte with eccentric and condensed chromatin.

Fig. 2

Plasmodium species-specific nested PCR. Lanes 1 and 5 show a DNA ladder marker (Bioneer, Daejeon, Korea). The Plasmodium genus can be identified from the presence of first-round amplification product (-1,000 bp, lane 2 and 6). Plasmodium species can be identified from the presence of second-round amplification products specific for P. falciparum (205 bp, lane 3), P. vivax (120 bp, lane 4), P. malariae (144 bp), and P. ovale (788 bp, lane 10) respectively. Only P. ovale DNA was detected from the patient's blood. Abbreviation: P, genus Plasmodium; Pv, P. vivax; Pf, P. falciparum; Pm, P. malariae; Po, P. ovale.

Fig. 3

Phylogenetic tree based on the small subunit ribosomal RNA genes of Plasmodium species including four registered P. ovale isolates (Nigerian I/CDC, Papua New Guinea, MAL/MAI, and CAG/Cameroon.) and P. ovale isolate (SM04-119, DQ104413) of this study. SM04-119 is more similar to the isolates of Nigerian I/CDC and Papua New Guinea than those of MAL/MAI and CAG/Cameroon.

References

1. Win TT, Jalloh A, Tantular IS, Tsuboi T, Ferreira MU, Kimura M, Kawamoto F. Molecular analysis of Plasmodium ovale variants. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004. 10:1235–1240.

2. Win TT, Lin K, Mizuno S, Zhou M, Liu Q, Ferreira MU, Tantular IS, Kojima S, Ishii A, Kawamoto F. Wide distribution of Plasmodium ovale in Myanmar. Trop Med Int Health. 2002. 7:231–239.

3. Kawamoto F, Liu Q, Ferreira MU, Tantular IS. How prevalent are Plasmodium ovale and P. malariae in East Asia? Parasitol Today. 1999. 15:422–426.

4. Faye FB, Spiegel A, Tall A, Sokhna C, Fontenille D, Rogier C, Trape JF. Diagnostic criteria and risk factors for Plasmodium ovale malaria. J Infect Dis. 2002. 186:690–695.

5. Mehlotra RK, Lorry K, Kastens W, Miller SM, Alpers MP, Bockarie M, Kazura JW, Zimmerman PA. Random distribution of mixed-species malaria infections in Papua New Guinea. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2000. 62:225–231.

6. Lee SY, Ko TS, Chi HS, Park YS. Four cases of the imported falciparum malaria in children. J Korean Pediatr Soc. 1997. 40:249–254.

7. Shin KS, Kim JS, Ryu SW, Suh IB, Lim CS. A case of Plasmodium vivax infection diagnosed after treatment of imported falciparum malaria. Korean J Clin Pathol. 2001. 21:360–364.

8. Soh CT, Lee KT, Im KI, Min DY, Ahn MH, Kim JJ, Yong TS. Current status of malaria in Korea. Yonsei Rep Trop Med. 1985. 16:11–18.

9. Snounou G, Viriyakosol S, Zhu XP, Jarra W, Pinheiro L, do Rosario VE, Thaithong S, Brown KN. High sensitivity of detection of human malaria parasites by the use of nested polymerase chain reaction. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1993. 61:315–320.

10. Warhurst DC, Williams JE. Laboratory diagnosis of malaria. J Clin Pathol. 1996. 49:533–538.

11. Richie TL. Interactions between malaria parasites infecting the same vertebrate host. Parasitology. 1988. 96:607–639.

12. May J, Mockenhaupt FP, Ademowo OG, Falusi AG, Olumese PE, Bienzle U, Meyer CG. High rate of mixed and subpatent malarial infections in southwest Nigeria. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1999. 61:339–343.

13. Qari SH, Shi YP, Pieniazek NJ, Collins WE, Lal AA. Phylogenetic relationship among the malaria parasites based on small subunit rRNA gene sequences: monophyletic nature of the human malaria parasite, Plasmodium falciparum. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 1996. 6:157–165.

14. Nzeyimana I, Henry MC, Dossou-Yovo J, Doannio JM, Diawara L, Carnevale P. The epidemiology of malaria in the southwestern forests of the Ivory Coast (Tai region). Bull Soc Pathol Exot. 2002. 95:89–94.

15. Rubio JM, Post RJ, van Leeuwen WM, Henry MC, Lindergard G, Hommel M. Alternative polymerase chain reaction method to identify Plasmodium species in human blood samples: the semi-nested multiplex malaria PCR (SnM-PCR). Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2002. 96:199–204.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download